Every year countless people stress over which wines to pair with their Thanksgiving dinner. These people also worry that their holiday might be a failure unless they have the correct wines. The holidays can be stressful enough without having to worry about the wine, especially when those worries are generally needless.

Cast your memory back to last year's Thanksgiving. Can you remember which specific wines you had with dinner? Can you remember the specific wines you had with Thanksgiving dinner two years ago?

I'm sure that most people won't be able to remember except maybe in the most general terms. Maybe they recall having had a Pinot Noir or a Riesling. They are unlikely to recall the specific producer or much else about the wine. What they are more likely to remember is the good (at least hopefully it was good) time they had, the family and friends that shared their table. They might remember whether the food and wine was good or bad but the specifics may be foggy.

Do you really need specific Thanksgiving wine recommendations? I don't think so. The more I ponder the question, the more I realize that all you need for Thanksgiving are some good wines, the varietals and/or blends being much less important. As long as they do not blatantly clash with the meal, then they should work just fine. And few wines are going to so blatantly clash. Drink wines you'll enjoy and don't worry so much about "perfect pairings."

A Thanksgiving meal is diverse, with many different flavors, from savory to sweet, and many different textures. No single wine is a perfect pairing with all these different dishes. So you need wines that people will enjoy in of their own right. I don't think too many hosts are seeking the "perfect" wine pairing. They simply want something that people will enjoy and which won't greatly detract from the food.

Plus, who will remember the wines next year?

We must also remember that any wine shared with good friends and family is likely to taste better, or at least seem that way, than one drank alone. The circumstances of the day, the good feelings, the fond memories, the thanks for the past year, will all lead to your wine seeming better. And it is all those surrounding circumstances that people will most remember about Thanksgiving. The wine will always take the back seat.

The wine is simply an extra, not a necessity. It pales in importance to everything else about the holiday. Like the Whos from "The Grinch Who Stole Xmas", there should still be joy even if all of the food and wine have been taken away.

I will probably bring a variety of wines to my Thanksgiving feast, a mix of sparkling wine, white, red and dessert wine. In general, I'll pick interesting and delicious wines that I feel people will enjoy. I won't spend much time worrying about pairing them with specific dishes and foods. I just want wines that will make people smile, that will enhance the spirit of the day.

Whatever you do for Thanksgiving, enjoy yourself and appreciate all that you have, rather than worry about what you do not.

(This is a revised version of a post from 2009. My basic sentiment has not changed one iota since that time and I felt it was important enough to raise it again.)

For Over 18 Years, and over 5500 articles, I've Been Sharing My Passion for Food, Wine, Saké & Spirits. Come Join Me & Satisfy Your Hunger & Thirst.

Important Info

▼

Monday, October 31, 2022

Wednesday, October 26, 2022

Vina Erdut: The World's Largest Wine Barrel (And a Card Playing Count)

One of the most awe-inspiring sights we witnessed in Slavonia, during our tour of Croatia, was the world's largest wine barrel which is still in use. Vina Erdut, the home of that cyclopean wine barrel, is also one of the largest wineries in Croatia, and owns one of biggest vineyards, in one piece, consisting of 400 hectares, in this part of Europe. In addition, Erdut has intriguing historical roots as well as some impressive views of the Danube River. If you're visiting this region of Croatia, you definitely should make a stop at Vina Erdut.

In 1984, their new winery was opened and it has an annual capacity of 6.5M liters (about 677K cases) however they only produce about 3.5M liters, and have no plans to expand. Their wine production is about 70% white and 30% red wine, and most is sold within Croatia, although they have recently started exporting a tiny amount to Scotland.

Wandering around the property, there is both a sense of history as well as a taste of beauty and serenity.

We then moved inside into their barrel room, where we would see the world's largest wine barrel.

The first photo fails to properly represent the enormity of the barrel, but this picture helps to provide some necessary context. With Todd Godbout (of Wine Compass) and I standing in front, dwarfed by this oak giant, you get a much better context for the great size of the barrel.

Quite a fun and exciting experience at Vina Erdut. That cyclopean wine barrel was awe-inspiring and I loved the history of the cellar. It's always such a beautiful site, well worth a visit.

In 1984, their new winery was opened and it has an annual capacity of 6.5M liters (about 677K cases) however they only produce about 3.5M liters, and have no plans to expand. Their wine production is about 70% white and 30% red wine, and most is sold within Croatia, although they have recently started exporting a tiny amount to Scotland.

We began our tour of Erdut in the oldest part of the cellar, from 1730, which was constructed by Baron Johann Baprista Maximilian Zuan. Over the doorway is a sign that states in Croatian: Cistu savest cisto vino nezelmo si bratjo ino jer u sreci iu bedi ovo ovoje mnoco vredi. It roughly translates as: "We don't want a clean conscience, clean wine, brother, because in happiness and in misery, this is worth a lot."

This cellar is naturally 13 degrees Celsius with 60% humidity, which is perfect for wine storage. Currently, they only store Sparkling wines here.

In 1778, Ivan Kapistran I. Adamovich de Csepin bought the property and his daughter, Fanny Adamovich Čepinska, took up residence on the property. She married Count Erwin Cech, who was relatively poor at the time, and it's said they often fought together. The Count had five large wine barrels built into the walls of the old cellar, although one of those barrels hid a great secret.

The Count was an avid card player, and it seems he didn't want his wife to know how often he played. So, one of those large barrels actually concealed a small room where the Count could hide, and play cards with a few friends. One time, he sent his wife a letter, claiming he was on a boat trip to Budapest, when he actually was playing cards in his secret wine barrel.

Upon the death of his wife, the Count then built an octagonal tower to the castle, which could accommodate four card players. He also remarried, to the Hungarian Countess Juliška, who had no problems with his card playing, so he didn't need to hide out in his barrel anymore.

Wandering around the property, there is both a sense of history as well as a taste of beauty and serenity.

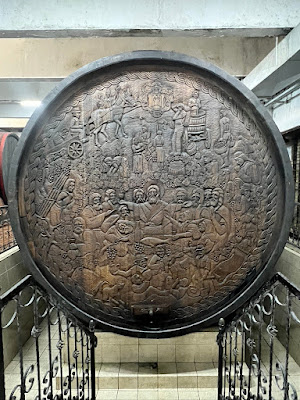

This is it! A huge barrel with a capacity of 75,000 liters, basically 100,000 wine bottles. The barrel was constructed in 1989 by DIK Đurđenovac, as part of a competition. The barrel was made from 109 Slavonian oak trees, basically a small forest. It's also held together by 3.5 tons of iron, the inside of the barrel is lined with wax, and the entire barrel, while empty, weighs about 20 tons, and 90-95 tons when it's full.

The first photo fails to properly represent the enormity of the barrel, but this picture helps to provide some necessary context. With Todd Godbout (of Wine Compass) and I standing in front, dwarfed by this oak giant, you get a much better context for the great size of the barrel.

Entry to the barrel is gained from the rear, and the barrel is filled each year with Graševina. It takes approximately 12+ hours to fill the entire barrel. As their website states: "It is always full of graševina, because graševina is the symbol of the whole wine-making area, as well as the company Erdutski vinogradi d.o.o."

The fascinating and intricate carvings on the front of the barrel were added about seven years after the barrel was completed. These carvings were created by Mato Tijardović and Fodor (I'm unsure of his first name), who are naive sculptors. Naive art generally refers to artists who lack professional training, and whose work is often straightforward and simple. In Croatia, there is even a Museum of Naive Art.

There is so much going on in this elaborate and beautiful carving such as a portrait of St. Martin, whose saint day is November 11. There's also a depiction of the Last Supper where Jesus is holding a chalice of wine. All of the images and scenes on the barrel are wine-related, and it added to the aw-inspiring beauty of the cyclopean barrel.

Standing near the huge barrel, we also tasted several wines, none of which were on the market yet. Of course we started with the 2020 Graševina, which had spent time in the enormous barrel. It's considered a "quality wine," not a "premium" one, and with a 13% ABV, it was crisp, fresh, dry and fruity, easy-drinking and pleasant. A nice every-day drinking wine, just fine on its own.

Standing near the huge barrel, we also tasted several wines, none of which were on the market yet. Of course we started with the 2020 Graševina, which had spent time in the enormous barrel. It's considered a "quality wine," not a "premium" one, and with a 13% ABV, it was crisp, fresh, dry and fruity, easy-drinking and pleasant. A nice every-day drinking wine, just fine on its own.

We also tasted the premium version of the 2020 Grasevina, with a 14% ABV, which had a similar profile except more complexity, a bit more richness, and a hint of spruce.

The 2021 Pinot Sivi (Gris), with a 14.7% ABV, was fruity and crisp, with a touch of apparent sweetness, and a nice character. The 2021 Rosé, with a 11.5% ABV, was produced from Cabernet Sauvignon. With a pleasant fruity aroma, it was dry and crisp, with bright strawberry flavors.

Some of the other wines they produce include the Traminer Aromatico, an ice wine, which is also their most awarded wine. Their first Sparkling wine is the Meander, a blend of Chardonnay and Pinot Noir. "Meander" refers to a location near the Danube, and that location is presented on the label.

The 2021 Pinot Sivi (Gris), with a 14.7% ABV, was fruity and crisp, with a touch of apparent sweetness, and a nice character. The 2021 Rosé, with a 11.5% ABV, was produced from Cabernet Sauvignon. With a pleasant fruity aroma, it was dry and crisp, with bright strawberry flavors.

Some of the other wines they produce include the Traminer Aromatico, an ice wine, which is also their most awarded wine. Their first Sparkling wine is the Meander, a blend of Chardonnay and Pinot Noir. "Meander" refers to a location near the Danube, and that location is presented on the label.

Tuesday, October 25, 2022

TRS Winery: From Carmenere to Cabernet Franc

Near the beginning of our tour of Croatia, at a wine event in Zagreb, one of the producers, TRS Winery, poured their Cabernet Franc. I'm very particular about this grape, and this wine appealed to my preferences, thoroughly impressing me with its depth, complexity and taste. Thus, I was excited to later visit the winery during our time in Slavonia.

They only produce about 2,000 bottles per year of premium wines. Most of their wine exports are to Bosnia and they have even established a company in Bosnia to handle the trade.

We got to visit the old wine cellar, which looks intimidating as you peer down the steps into the darkness. Tentatively, you walk down the steps, being careful not to fall, and you enter the darkness, using your cellphones as a light source. There is a sense of great age as you wander the darkened area, and you can see the potential for this cellar once it has some renovations.

Zlatko led us through a tasting of some of their wines, beginning with the 2021 Sauvignon Blanc, which was bright and fresh, with notes of lemon and citrus. An easy drinking wine, great for the summer.

We then moved onto some tank tastings of Graševina, a few from the 2021 vintage. There were definitely differences in the various tanks, even from the same vintage, especially as some were from different vineyards. The wines were generally quite good, with lots of potential. Graševina does so well in Slavonia.

We then moved onto some bottled wines, such as the 2020 Grasevina, which was fresh and bright, with delicious apple flavors, good acidity, and a pleasing finish. The 2015 Grasevina, with a 13% ABV, was intriguing with a more intense and deeper flavor, with less fruit notes, a hint of smoke, and a mild spice element. This is a wine that best works with food, and is also indicative of how well that Grasevina can age.

The 2018 3C is a wine that was originally created out of a mistake. Initially, they wanted to use Frankovka in this wine, and it took them five years to realize that the grape they were actually using was Carmenere, and not Frankovka. They decided to keep the Carmenere, and the wine became "3C", a blend of Carmenere, Cabernet Franc, and Cabernet Sauvignon. With a 14.5% ABV, this wine was delicious, with pleasant red fruit flavors, low tannins, good acidity and some nice complexity. The blend works so well, and is definitely more unique in Croatia. This is probably one of the only wineries that uses Carmenere in Croatia. Highly recommended.

The 2016 Cabernet Sauvignon, with a 15% ABV, was easy drinking and fruity (although not jammy) with restrained tannins. A good pizza and burger wine.

The 2017 Cabernet Franc. with a 15% ABV, impressed me once again, being big, bold, and intense, with a complex melange of red and black fruits with mild spice notes. The finish was lengthy and satisfying, and it would pair well with hearty dishes or a nice steak. Highly recommended.

TRS Winery is producing some excellent wines, from its Grasevina to Cabernet Franc. It's still a relatively young winery, and its future looks bright. I brought home a bottle of the 2018 3C, and probably will open it this upcoming holiday season, sharing it with family and friends.

Two friends, Zlatko (pictured above) and Marijo, had been making small amounts of wine, using purchased grapes, but they were desirous of having more control one the process. They wanted to own their own vineyards, and did so, although initially they began making wine separately, a total capacity of 30K liters. They eventually realized they might do better working together, so they united in 2003 and founded the TRS cooperative winery in 2007. Trs roughly translates as "vine." This new winery increased their capacity to 80K liters and owned 29 hectares of vineyards.

Since that time, the cooperative has significantly grown so now that it includes sixteen members, 70 hectares, and the total capacity is about 550K liters, although annual production is only about 300K-350K liters. Their production is about 70% white wine and 30% red. Their white grapes include Graševina, Chardonnay, Rhine Riesling, Traminac, Sauvignon Blanc and Muscat Blanc while their red grapes include Frankovka, Cabernet Sauvignon and Cabernet Franc.

The original wine building at their location is from 1885, with a wine cellar from the 18th century. In 2009, when they purchased the winery, they renovated the historic building and have plans for the wine cellar as well. They want to build a tunnel between the two wine cellars.

They only produce about 2,000 bottles per year of premium wines. Most of their wine exports are to Bosnia and they have even established a company in Bosnia to handle the trade.

The 18th century wine cellar entrance is on the left side of the photo.

We got to visit the old wine cellar, which looks intimidating as you peer down the steps into the darkness. Tentatively, you walk down the steps, being careful not to fall, and you enter the darkness, using your cellphones as a light source. There is a sense of great age as you wander the darkened area, and you can see the potential for this cellar once it has some renovations.

Zlatko led us through a tasting of some of their wines, beginning with the 2021 Sauvignon Blanc, which was bright and fresh, with notes of lemon and citrus. An easy drinking wine, great for the summer.

We then moved onto some tank tastings of Graševina, a few from the 2021 vintage. There were definitely differences in the various tanks, even from the same vintage, especially as some were from different vineyards. The wines were generally quite good, with lots of potential. Graševina does so well in Slavonia.

We then moved onto some bottled wines, such as the 2020 Grasevina, which was fresh and bright, with delicious apple flavors, good acidity, and a pleasing finish. The 2015 Grasevina, with a 13% ABV, was intriguing with a more intense and deeper flavor, with less fruit notes, a hint of smoke, and a mild spice element. This is a wine that best works with food, and is also indicative of how well that Grasevina can age.

The 2018 3C is a wine that was originally created out of a mistake. Initially, they wanted to use Frankovka in this wine, and it took them five years to realize that the grape they were actually using was Carmenere, and not Frankovka. They decided to keep the Carmenere, and the wine became "3C", a blend of Carmenere, Cabernet Franc, and Cabernet Sauvignon. With a 14.5% ABV, this wine was delicious, with pleasant red fruit flavors, low tannins, good acidity and some nice complexity. The blend works so well, and is definitely more unique in Croatia. This is probably one of the only wineries that uses Carmenere in Croatia. Highly recommended.

The 2016 Cabernet Sauvignon, with a 15% ABV, was easy drinking and fruity (although not jammy) with restrained tannins. A good pizza and burger wine.

The 2017 Cabernet Franc. with a 15% ABV, impressed me once again, being big, bold, and intense, with a complex melange of red and black fruits with mild spice notes. The finish was lengthy and satisfying, and it would pair well with hearty dishes or a nice steak. Highly recommended.

Monday, October 24, 2022

The Origins of Chinese Lobster Sauce

If you order Lobster Sauce at a Chinese restaurant, most people realize that it doesn’t contain any lobster, and that the ground meat in the sauce is actually pork. On most menus, you'll see Shrimp with Lobster Sauce, though many Chinese restaurants also sell the lobster sauce on its own, which you can then serve over white rice. In addition, there are two different kinds of lobster sauce, dependent in large part on your part of the country. In New England, lobster sauce tends to be a brown sauce while it is more of a white sauce in the rest of the country.

The Chinese term for lobster is 龍蝦 (lóngxiā), which roughly translates as "dragon shrimp." In Chinese culture, the dragon represents good fortune and longevity, which they also associate with lobsters.

What is the origin of lobster sauce? Why is it called lobster sauce when it contains no lobster? And why are there two different versions?

Most online sources are of little help in answering these questions, presenting claims without any supporting evidence. Many of these sources believe that lobster sauce originated during the 1950s. These sources also claim that lobster sauce was first used in a different dish, Lobster Cantonese Style, but because of the expense of lobster, a variant dish was created, using shrimp instead of lobster but with the same sauce. Those same sources also provide no real explanation for the regional differences of the sauce.

I agree that the origins of Chinese lobster sauce are murky, but my own research was enlightening in a number of regards. The origins of this dish extend back at least to 1898, when Lobster Cantonese Style was referred to as Chow Loong Har, and there's no proof that "high-priced" lobster led to the replacement with shrimp. In fact, the opposite is true, that shrimp were more expensive than lobster during the 1930s and 1940s. In addition, I have some insight into a possible explanation of the regional differences in the sauce.

There’s evidence that lobster was on the menu at Chinese restaurants in the U.S. at least near the end of the 19th century. For example, the Boston Globe, December 16, 1893, described how the Hong Far Low restaurant, in Chinatown, hosted a special banquet and the menu included fried lobster, birds' nest soup, abalone, fried pigeons, and shark's fin. The Boston Herald, August 18, 1895, reported on a dinner at a new Chinese spot, the Oriental Restaurant, in Boston's Chinatown. One of the courses was “fried lobster,” although there wasn't a mention of any sauce associated with the dish. More lobster dishes were available at this restaurant as well, including Plain Lobster and Lobster Omelet.

The Providence Sunday Journal (RI), March 29, 1896, in an article on slumming in Boston's Chinatown, noted that the largest Chinese restaurant served items including fried lobster (75 cents), chop sooy (25 cents), chow mein (75 cents) and fried boneless chicken (75 cents). It's interesting to see that the lobster and chicken cost the same price.

An interesting book, New York’s Chinatown: An Historical Presentation of its People and Places by Louis J. Beck (NY, 1898), described the various Chinese restaurants in New York City. It was stated there were seven first-class restaurants, which served similar menus. One of those common dishes, priced at 75 cents, was Chow Loong Har (Fried Lobster with Vegetable). This dish was the same price as Fried Boned Chicken and Fried Pig's Paunches.

However, Chow Loong Har is more commonly known as Lobster Cantonese Style, and this may be the first appearance of this dish in a U.S. book or newspaper. Obviously, this dish could have existed prior to this time, but it wasn't noted in any other newspaper or book. Unfortunately, a fuller description of this dish, especially of the sauce, wasn't provided.

The Charlotte News (NC), August 4, 1900, published a menu for the Oriental Restaurant, which offered Plain Lobster (50 cents), Fried Lobster (75 cents), and Lobster Omelet (75 cents). Although Chop Sooy (25 cents) was quite cheap, their Chow Mein (75 cents) was priced similarly to the lobster dishes. Even the Fried Boneless Chicken (75 cents) was a similar price. So, considering the prices, lobster didn’t seem a luxury dish at this point. After this date, numerous Chinese restaurants would offer a wide variety of lobster dishes, from Chop Suey to Chow Mein.

The Courier-Journal (KY), February 8, 1904, noted that at a Chinese New Year’s celebration, one of the dishes served was Chow Loong Har, which was stated to be “fried lobster with vegetables.” As I mentioned above, this dish is more commonly known as Lobster Cantonese Style.

The Boston Herald, March 21, 1907, reported that Governor Guild had been greatly feted in Chinatown, hosted by the Chinese Merchants' Association. A banquet was held at the Red Dragon restaurant, "the most noted restaurant in Chinatown," and 14 courses were served, including, "lobster a la red dragon." Unfortunately that dish wasn't described.

As for other lobster dishes, Lobster Chop Suey (Chow Sarm Hal) made its appearance in an ad in the Oshkosh Northwestern (WI), September 12, 1907, and was also mentioned in the Fort Worth Star-Telegram (TX), November 27, 1907. There would be references to Lobster Chow Mein in the Boston Post, April 7, 1916, and Lobster Chop Suey in the Boston Post, November 27, 1918. Lobster was a popular ingredient at this time.

“Fried Lobster-Canton Style” made another appearance in the newspapers, in a restaurant ad in the Fall River Daily Evening News (MA), August 20, 1916. Unfortunately, once again, there was no description of the sauce.

More Lobster dishes. The Nebraska Signal (NE), November 10, 1921, presented a restaurant menu with various lobster dishes including Lobster Chop Sui (50 cents), which was the same price as Chicken Chop Sui. Lobster Chow Min (75 cents) was also the same price as Chicken Chow Min. Other items included Lobster Egg Fu Yung (35 cents), Fried Lobster with Vegetable (50 cents), Fried Lobster with Waterbeans (35 cents) and Fried Lobster with Green Pepper & Tomatoes (50 cents). As we can see, lobster prices were comparable to chicken dishes, so it still wasn’t a luxury item. Ten years later, the Evening Vanguard (CA), August 20, 1931, printed a recipe for Lobster Chop Suey.

The Chinese love of lobsters! The Boston Herald, April 4, 1931, reported that "That Chinese are also big buyers and connoisseurs of lobsters. For some reason best known to themselves, the Chinese restaurant proprietors, who customarily do their own shopping, almost always pick out female lobsters and refuse to buy males."

During the 1930s, Lobster Cantonese Style began to make more frequent appearances in various newspapers. The Evening Bulletin (RI), May 2, 1932, printed an advertisement for the 6th Anniversary of the Port Arthur restaurant, and its menu included "Chow Loong Har (Live lobster stuffed Chinese Style)" for 80 cents. The Greenwood Commonwealth (MS), June 29, 1934, mentioned “Chinese lobster (Canton style)” while the Brooklyn Daily Eagle (NY), August 7, 1935, had a restaurant ad mentioning “fried lobster, Cantonese style.”

A recipe for "Shrimp with Lobster Sauce" also appeared in 1940. The Record-Argus (PA), May 4, 1940, provided that recipe for “shrimp with a tasty lobster sauce.” The recipe would be reprinted in newspapers in Texas, New York, Minnesota, Illinois, Indiana, Wisconsin, Maine, New Jersey, and Ohio. However, this was not a Chinese version, didn't resemble Lobster Cantonese Style, and actually used lobster in the recipe.

Continued mentions of this lobster sauce occurred into the 1940s. The Morning Call (NJ), April 2, 1940, noted a Chinese restaurant that served “fresh shrimp with lobster sauce” while the Montclair Times (NJ), November 22, 1940, noted a different Chinese restaurant that also offered “fresh shrimp with lobster sauce.” The Atlantic City Press (NJ), November 29, 1940, had an ad for the Far East restaurant, serving “Special Fried Jumbo Shrimp with Lobster Sauce.” The Evening Sun (MD), December 6, 1940, referenced a Chinese menu for a special event which served “Shrimp with lobster sauce” while the Miami News (FL), February 19, 1941, stated that Ruby Foo’s offered “shrimp with lobster sauce.”

The Brooklyn Eagle (NY), May 5, 1941, provided a recipe for Chow Loong Har, aka Lobster Cantonese Style, calling for lobster and ground pork, but no soy sauce.

In an ad for the Fu Manchu restaurant, in the Miami News (FL), August 20, 1941, it said, “Shrimp with Lobster Sauce is our own creation! Culinary critics say it is beyond compare. Enjoy this seafood masterpiece at The House of Fu Manchu.” No further description of the dish was given.

The Trenton Evening Times (NJ), April 2, 1942, printed a PIC of recipe for "Chow-Loong-Har (Canton Lobster)." The recipe called for "lean pork" as well as actual lobster, and soy sauce was an ingredient although black beans were omitted.

The Savannah Evening Press (GA), April 4, 1942, mentioned a Chinese restaurant which served "Fried Shrimp with Lobster Sauce." The Washington Daily News (D.C.), August 29, 1942, also mentioned a Chinese restaurant which served "Fried Jumbo Shrimp with Lobster Sauce." And in a restaurant advertisement in the Central New Jersey Home News (NJ), December 6, 1946, the dish was referred to as “Foo-Young Har-Kow (Fresh jumbo shrimp with lobster sauce).”

We finally got a peek into the contents of lobster sauce, in a recipe provided in the Boston Globe (MA), December 19, 1946. The recipe for Shrimp with Lobster Sauce had been submitted from a reader, who claimed they received it from Chinese cook in Arizona. The recipe first listed the ingredients: “One-half to 1 pound raw shrimp, 1 rounded teaspoon black beans, 2 cloves garlic, ½ cup peanut oil, 1 cup water, 1 teaspoon gourmet powder, dash pepper, 3 eggs, 3 scallions with tops, 2 teaspoons corn starch.”

The Tampa Bay Times (FL), April 10, 1949, published a menu for the China Inn noting that Fresh Shrimp with Lobster Sauce cost $2.25 while Fried Whole Lobster Cantonese Style cost $2.50. A very minor difference in price. There was another menu presented in the News-Journal (OH), April 24, 1949, which had a larger difference, with Fried Shrimp with Lobster Sauce for $1.35 and Fried Lobster Cantonese Style for $2.25. And in the Evening Star (D.C.), September 25, 1949, there was a menu that offered Shrimp, Lobster Sauce for $1.50 and Lobster, Cantonese Style for $2.00.

A new name for shrimp with lobster sauce. The Evening Sun (MD), November 8, 1948, published a restaurant ad which referred to shrimp with lobster sauce as Har Loong Woo. The ad also stated their jumbo shrimp had the same sauce as their Lobster Cantonese.

The Los Angeles Mirror (CA), November 9, 1948, explained a bit about the contents of lobster sauce in a review of the Ming Room restaurant. It noted “Canton Shrimp with lobster sauce (garlic, egg, chopped pork, and soy bean).”

Another recipe was presented in the Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph (PA), August 28, 1949, for Shrimps with Lobster Sauce, and the ingredients included: ½ lb. finely ground lean pork, 1 tbsp. minced carrot, 1 tbsp minced celery, 1 tsp. salt, dash pepper, ¼ cup fat or salad oil, 1 tsp salt, dash pepper, 1 clove garlic, 1 cup bouillon, 2 lbs. raw shrimps, 1 egg slightly beaten, 2 tbsps cornstarch, ¼ water, and 2 tbsp minced scallions. This is similar to the prior recipe from the Trenton Evening Times (NJ), April 2, 1942. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle (NY), September 22, 1949, presented a similar recipe for Shrimp with Lobster Sauce, Cantonese.

A variant recipe arose during the 1950s. The Boston Globe, January 22, 1952, published a recipe from one of their readers for Chinese Lobster Sauce. First, you made a mix of salt, pepper, chopped pork, carrot, celery, and scallion or onion. You then fried lobster with the pork, some bouillon, and an egg. Finally, you blended cornstarch, soy sauce, and water, and added it to the sauce.

A cookbook recipe. The Ancestral Recipes of Shen Mei Lon (1954) provided a recipe Chow Loong Har, Lobster Cantonese. This recipe called for lobster, ground pork and soy sauce.

The Boston Sunday Advertiser, December 16, 1956, also provided a recipe for Shrimp with Lobster Sauce, and the ingredients included both light and heavy soy sauce. The Boston Globe (MA), August 19, 1962, had a recipe for Foo-Young-Har-Kow (shrimp with lobster sauce) which used soy sauce and gravy darkener. This would clearly make a darker lobster sauce.

The Chinatown Handy Guide San Francisco (1959), had its own recipe for Shrimp with Lobster Sauce, which didn't call for lobster, but did call for ground pork and soy sauce. This is very similar to the modern version of this dish.

Nowadays, lobster sauce in New England is commonly a brown sauce, while it remains generally white in the rest of the country. Why the difference? I'll address that issue shortly.

A couple explanations were provided for the name of lobster sauce. The Boston Globe, November 29, 1962, published a letter from a reader who stated he was told by a Chinese restaurant owner, of over 30 years, that “lobster sauce never contained lobster. It is called lobster sauce merely because it is usually served over lobster or other sea foods. The trend is now to serve lobster sauce with shrimp.”

The Chinese term for lobster is 龍蝦 (lóngxiā), which roughly translates as "dragon shrimp." In Chinese culture, the dragon represents good fortune and longevity, which they also associate with lobsters.

What is the origin of lobster sauce? Why is it called lobster sauce when it contains no lobster? And why are there two different versions?

Most online sources are of little help in answering these questions, presenting claims without any supporting evidence. Many of these sources believe that lobster sauce originated during the 1950s. These sources also claim that lobster sauce was first used in a different dish, Lobster Cantonese Style, but because of the expense of lobster, a variant dish was created, using shrimp instead of lobster but with the same sauce. Those same sources also provide no real explanation for the regional differences of the sauce.

I agree that the origins of Chinese lobster sauce are murky, but my own research was enlightening in a number of regards. The origins of this dish extend back at least to 1898, when Lobster Cantonese Style was referred to as Chow Loong Har, and there's no proof that "high-priced" lobster led to the replacement with shrimp. In fact, the opposite is true, that shrimp were more expensive than lobster during the 1930s and 1940s. In addition, I have some insight into a possible explanation of the regional differences in the sauce.

There’s evidence that lobster was on the menu at Chinese restaurants in the U.S. at least near the end of the 19th century. For example, the Boston Globe, December 16, 1893, described how the Hong Far Low restaurant, in Chinatown, hosted a special banquet and the menu included fried lobster, birds' nest soup, abalone, fried pigeons, and shark's fin. The Boston Herald, August 18, 1895, reported on a dinner at a new Chinese spot, the Oriental Restaurant, in Boston's Chinatown. One of the courses was “fried lobster,” although there wasn't a mention of any sauce associated with the dish. More lobster dishes were available at this restaurant as well, including Plain Lobster and Lobster Omelet.

The Providence Sunday Journal (RI), March 29, 1896, in an article on slumming in Boston's Chinatown, noted that the largest Chinese restaurant served items including fried lobster (75 cents), chop sooy (25 cents), chow mein (75 cents) and fried boneless chicken (75 cents). It's interesting to see that the lobster and chicken cost the same price.

An interesting book, New York’s Chinatown: An Historical Presentation of its People and Places by Louis J. Beck (NY, 1898), described the various Chinese restaurants in New York City. It was stated there were seven first-class restaurants, which served similar menus. One of those common dishes, priced at 75 cents, was Chow Loong Har (Fried Lobster with Vegetable). This dish was the same price as Fried Boned Chicken and Fried Pig's Paunches.

However, Chow Loong Har is more commonly known as Lobster Cantonese Style, and this may be the first appearance of this dish in a U.S. book or newspaper. Obviously, this dish could have existed prior to this time, but it wasn't noted in any other newspaper or book. Unfortunately, a fuller description of this dish, especially of the sauce, wasn't provided.

The Charlotte News (NC), August 4, 1900, published a menu for the Oriental Restaurant, which offered Plain Lobster (50 cents), Fried Lobster (75 cents), and Lobster Omelet (75 cents). Although Chop Sooy (25 cents) was quite cheap, their Chow Mein (75 cents) was priced similarly to the lobster dishes. Even the Fried Boneless Chicken (75 cents) was a similar price. So, considering the prices, lobster didn’t seem a luxury dish at this point. After this date, numerous Chinese restaurants would offer a wide variety of lobster dishes, from Chop Suey to Chow Mein.

The Courier-Journal (KY), February 8, 1904, noted that at a Chinese New Year’s celebration, one of the dishes served was Chow Loong Har, which was stated to be “fried lobster with vegetables.” As I mentioned above, this dish is more commonly known as Lobster Cantonese Style.

The Boston Herald, March 21, 1907, reported that Governor Guild had been greatly feted in Chinatown, hosted by the Chinese Merchants' Association. A banquet was held at the Red Dragon restaurant, "the most noted restaurant in Chinatown," and 14 courses were served, including, "lobster a la red dragon." Unfortunately that dish wasn't described.

As for other lobster dishes, Lobster Chop Suey (Chow Sarm Hal) made its appearance in an ad in the Oshkosh Northwestern (WI), September 12, 1907, and was also mentioned in the Fort Worth Star-Telegram (TX), November 27, 1907. There would be references to Lobster Chow Mein in the Boston Post, April 7, 1916, and Lobster Chop Suey in the Boston Post, November 27, 1918. Lobster was a popular ingredient at this time.

“Fried Lobster-Canton Style” made another appearance in the newspapers, in a restaurant ad in the Fall River Daily Evening News (MA), August 20, 1916. Unfortunately, once again, there was no description of the sauce.

More Lobster dishes. The Nebraska Signal (NE), November 10, 1921, presented a restaurant menu with various lobster dishes including Lobster Chop Sui (50 cents), which was the same price as Chicken Chop Sui. Lobster Chow Min (75 cents) was also the same price as Chicken Chow Min. Other items included Lobster Egg Fu Yung (35 cents), Fried Lobster with Vegetable (50 cents), Fried Lobster with Waterbeans (35 cents) and Fried Lobster with Green Pepper & Tomatoes (50 cents). As we can see, lobster prices were comparable to chicken dishes, so it still wasn’t a luxury item. Ten years later, the Evening Vanguard (CA), August 20, 1931, printed a recipe for Lobster Chop Suey.

The Chinese love of lobsters! The Boston Herald, April 4, 1931, reported that "That Chinese are also big buyers and connoisseurs of lobsters. For some reason best known to themselves, the Chinese restaurant proprietors, who customarily do their own shopping, almost always pick out female lobsters and refuse to buy males."

During the 1930s, Lobster Cantonese Style began to make more frequent appearances in various newspapers. The Evening Bulletin (RI), May 2, 1932, printed an advertisement for the 6th Anniversary of the Port Arthur restaurant, and its menu included "Chow Loong Har (Live lobster stuffed Chinese Style)" for 80 cents. The Greenwood Commonwealth (MS), June 29, 1934, mentioned “Chinese lobster (Canton style)” while the Brooklyn Daily Eagle (NY), August 7, 1935, had a restaurant ad mentioning “fried lobster, Cantonese style.”

The Hartford Courant (CT), October 9, 1936, also published a restaurant ad noting “Chinese Fried Lobster.” The Times Dispatch (VA). December 3, 1938, mentioned a New York City restaurant serving “Chow Loong Ha (Lobster Cantonese Style)” while the Hartford Courant (CT), December 18, 1938, also noted a new restaurant in New York City that served “fried lobster, Cantonese style.”

However, what was Lobster Cantonese Style? None of these prior newspaper references actually explained the nature of this dish. Some sources claim that it was based on a dish from China, where the sauce was made with ginger and scallions. However, when we finally get a description of the lobster Cantonese Style sauce, it differed significantly from the recipes for Lobster with Ginger & Scallions Sauce. For example, the former usually didn't include the use of soy sauce or ginger though the latter sauce did. In addition, the former included the use of minced pork but the latter sauce did not.

The Times Union (NY), April 17, 1938, presented the first newspaper recipe for Lobster Cantonese. The ingredients for this dish included 1 large boiled lobster, chopped pork, eggs, black beans, scallions, salt, sugar, gourmet powder, corn starch, meat stock or water, and garlic. If this recipe was reflective of the dish at most Chinese restaurants, it shows the differences from Lobster with Ginger & Scallions. It would thus be a significant variation of the original lobster dish. I'll note that no soy sauce was included in this recipe. Without the lobster, this sauce would be close to some modern versions of Lobster Sauce.

A cookbook from 1938 seems to give support to the idea that this recipe was the norm. Cook at Home In Chinese by Henry Low presented a recipe for Lobster Cantonese Style (Chow Loong Ha). Henry was the chef at the famed Port Arthur Restaurant, in New York’s Chinatown, which was opened in 1897 by Chu Gam Fai. Henry worked there for at least ten years, starting in 1928. It stands to reason that the recipe he provided in his cookbook would reflect that served at the Port Arthur Restaurant. The ingredients for his recipe included 1 large lobster, chopped raw lean pork, eggs, black beans, scallions, garlic, salt, pepper, gourmet powder, cornstarch, and stock or water. Very similar to the previous newspaper recipe. And once again, soy sauce and ginger were not used.

1938 was also the year when the phrase "Shrimp with Lobster Sauce" was first mentioned. The Bangor Daily Commercial (ME), March 11, 1938, had an ad for the Pekin Garden restaurant which stated, “try our Fried Fresh Shrimps with Lobster Sauce.” The Montclair Times (NJ), March 11, 1938, also mentioned a New York City Chinese restaurant which served “fresh shrimp with lobster sauce.” The Intelligencer Journal (PA), October 1, 1938, printed an ad for a Chinese restaurant offering “Fried, Fresh Shrimp with Lobster Sauce.” The Milwaukee Sentinel (WI), November 1, 1938, ran ad ad for a Chinese restaurant which served “Fresh Shrimp, Cantonese Style.” And the Evening Bulletin (RI), June 16, 1939, had an ad for the Pagoda Restaurant, which offered “Fried Fresh Shrimp with Lobster Sauce."

However, none of these ads described the “lobster sauce.” Did it actually contain lobster, or was it something very different?

Continued mentions of lobster sauce occurred into the 1940s. The Morning Call (NJ), April 2, 1940, noted a Chinese restaurant that served “fresh shrimp with lobster sauce”

However, what was Lobster Cantonese Style? None of these prior newspaper references actually explained the nature of this dish. Some sources claim that it was based on a dish from China, where the sauce was made with ginger and scallions. However, when we finally get a description of the lobster Cantonese Style sauce, it differed significantly from the recipes for Lobster with Ginger & Scallions Sauce. For example, the former usually didn't include the use of soy sauce or ginger though the latter sauce did. In addition, the former included the use of minced pork but the latter sauce did not.

The Times Union (NY), April 17, 1938, presented the first newspaper recipe for Lobster Cantonese. The ingredients for this dish included 1 large boiled lobster, chopped pork, eggs, black beans, scallions, salt, sugar, gourmet powder, corn starch, meat stock or water, and garlic. If this recipe was reflective of the dish at most Chinese restaurants, it shows the differences from Lobster with Ginger & Scallions. It would thus be a significant variation of the original lobster dish. I'll note that no soy sauce was included in this recipe. Without the lobster, this sauce would be close to some modern versions of Lobster Sauce.

A cookbook from 1938 seems to give support to the idea that this recipe was the norm. Cook at Home In Chinese by Henry Low presented a recipe for Lobster Cantonese Style (Chow Loong Ha). Henry was the chef at the famed Port Arthur Restaurant, in New York’s Chinatown, which was opened in 1897 by Chu Gam Fai. Henry worked there for at least ten years, starting in 1928. It stands to reason that the recipe he provided in his cookbook would reflect that served at the Port Arthur Restaurant. The ingredients for his recipe included 1 large lobster, chopped raw lean pork, eggs, black beans, scallions, garlic, salt, pepper, gourmet powder, cornstarch, and stock or water. Very similar to the previous newspaper recipe. And once again, soy sauce and ginger were not used.

1938 was also the year when the phrase "Shrimp with Lobster Sauce" was first mentioned. The Bangor Daily Commercial (ME), March 11, 1938, had an ad for the Pekin Garden restaurant which stated, “try our Fried Fresh Shrimps with Lobster Sauce.” The Montclair Times (NJ), March 11, 1938, also mentioned a New York City Chinese restaurant which served “fresh shrimp with lobster sauce.” The Intelligencer Journal (PA), October 1, 1938, printed an ad for a Chinese restaurant offering “Fried, Fresh Shrimp with Lobster Sauce.” The Milwaukee Sentinel (WI), November 1, 1938, ran ad ad for a Chinese restaurant which served “Fresh Shrimp, Cantonese Style.” And the Evening Bulletin (RI), June 16, 1939, had an ad for the Pagoda Restaurant, which offered “Fried Fresh Shrimp with Lobster Sauce."

However, none of these ads described the “lobster sauce.” Did it actually contain lobster, or was it something very different?

Continued mentions of lobster sauce occurred into the 1940s. The Morning Call (NJ), April 2, 1940, noted a Chinese restaurant that served “fresh shrimp with lobster sauce”

It's important to note that during the 1930s and 1940s, lobster was actually less expensive than shrimp, which was seen far more as a luxury ingredient than lobster. So, the claim that shrimp with lobster sauce was created due to the expense of lobster lacks any foundation or evidence. If anything, shrimp with lobster sauce should have been a pricier dish, as shrimp were a luxury item.

A recipe for "Shrimp with Lobster Sauce" also appeared in 1940. The Record-Argus (PA), May 4, 1940, provided that recipe for “shrimp with a tasty lobster sauce.” The recipe would be reprinted in newspapers in Texas, New York, Minnesota, Illinois, Indiana, Wisconsin, Maine, New Jersey, and Ohio. However, this was not a Chinese version, didn't resemble Lobster Cantonese Style, and actually used lobster in the recipe.

Continued mentions of this lobster sauce occurred into the 1940s. The Morning Call (NJ), April 2, 1940, noted a Chinese restaurant that served “fresh shrimp with lobster sauce” while the Montclair Times (NJ), November 22, 1940, noted a different Chinese restaurant that also offered “fresh shrimp with lobster sauce.” The Atlantic City Press (NJ), November 29, 1940, had an ad for the Far East restaurant, serving “Special Fried Jumbo Shrimp with Lobster Sauce.” The Evening Sun (MD), December 6, 1940, referenced a Chinese menu for a special event which served “Shrimp with lobster sauce” while the Miami News (FL), February 19, 1941, stated that Ruby Foo’s offered “shrimp with lobster sauce.”

The Brooklyn Eagle (NY), May 5, 1941, provided a recipe for Chow Loong Har, aka Lobster Cantonese Style, calling for lobster and ground pork, but no soy sauce.

In an ad for the Fu Manchu restaurant, in the Miami News (FL), August 20, 1941, it said, “Shrimp with Lobster Sauce is our own creation! Culinary critics say it is beyond compare. Enjoy this seafood masterpiece at The House of Fu Manchu.” No further description of the dish was given.

The Trenton Evening Times (NJ), April 2, 1942, printed a PIC of recipe for "Chow-Loong-Har (Canton Lobster)." The recipe called for "lean pork" as well as actual lobster, and soy sauce was an ingredient although black beans were omitted.

The Savannah Evening Press (GA), April 4, 1942, mentioned a Chinese restaurant which served "Fried Shrimp with Lobster Sauce." The Washington Daily News (D.C.), August 29, 1942, also mentioned a Chinese restaurant which served "Fried Jumbo Shrimp with Lobster Sauce." And in a restaurant advertisement in the Central New Jersey Home News (NJ), December 6, 1946, the dish was referred to as “Foo-Young Har-Kow (Fresh jumbo shrimp with lobster sauce).”

We finally got a peek into the contents of lobster sauce, in a recipe provided in the Boston Globe (MA), December 19, 1946. The recipe for Shrimp with Lobster Sauce had been submitted from a reader, who claimed they received it from Chinese cook in Arizona. The recipe first listed the ingredients: “One-half to 1 pound raw shrimp, 1 rounded teaspoon black beans, 2 cloves garlic, ½ cup peanut oil, 1 cup water, 1 teaspoon gourmet powder, dash pepper, 3 eggs, 3 scallions with tops, 2 teaspoons corn starch.”

Then, it provided the directions: “Soak black beans until soft; crush with garlic. Heat oil in heavy skillet, add raw shrimp, beans and garlic. Saute for 3 to 5 minutes. Add water, gourmet powder and pepper. Cover and cook for eight minutes. Chop scallions with tops into ¼-inch pieces; add to eggs and stir slightly until yolks are broken. While shrimp mixture is boiling pour the scallion-egg mixture into the shrimp. Stir slightly and cook until egg is done. The egg should be cooked into shred-like pieces if mixing is done properly. Mix corn starch in enough water to form a smooth paste. Add to shrimp, stir and cook 2 min. Salt to taste.”

This is essentially the recipe for the same sauce used in Lobster Cantonese Style, however it lacked ground pork. So, “lobster sauce” may have acquired its name because it was the same sauce as that used in Lobster Cantonese Style. Shrimp was, for unknown reasons, substituted for the lobster.

Now, it would have made sense to refer to this dish as “Shrimp Cantonese Style” rather than call it “Shrimp with Lobster Sauce.” And actually, there were mentions of that exact name, extending back at least to 1938. The Columbus News (NE), December 22, 1938, briefly mentioned that someone’s favorite dish was “Shrimp Cantonese.” The Detroit Free Press (MI), January 30, 1941, mentioned a Detroit chef who made “a better shrimp, Cantonese.” Other references were in the Southwest Wave (CA), September 19, 1946, “Fried Shrimp, Cantonese style” and the Herald-News (NJ), April 4, 1947, “Fragrant Jumbo Shrimp—Cantonese Style.” The Tampa Bay Times (FL), January 3, 1948, noted that a restaurant dinner party served “breaded shrimp Cantonese” while a restaurant ad in the Pike County Dispatch (PA), July 1, 1948, included “Lobster Cantonese” and “Shrimp Cantonese.”

However, it seems that the term Lobster Sauce eventually became the more popular term, so that Shrimp Cantonese became much less common over the years. When the term shrimp with lobster sauce was first used, did customers know that the sauce didn't include any actual lobster? However, it seems like some of the earliest dishes of shrimp with lobster sauce might actually have included some lobsters. The menus probably didn't mentioned whether the dish contained actual lobster or not, and it's possible numerous customers didn't know they were eating minced pork rather than minced lobster. Unfortunately, none of the newspapers during this period addressed this issue.

Lobster prices! How much did these dishes cost in the late 1940s? The Baltimore Sun (MD), July 5, 1947, presented a restaurant ad, noting that their week’s special was a dinner of Lobster Cantonese Style, including soup or appetizer, rice, dessert and drink. The lobsters were shipped directly from Maine. The dish normally cost $2 but was on special for $1.25. In September 1947, that same restaurant ran another special, but only lowered the lobster dish to $1.50.

The New York Post (NY), December 5, 1947, provided a recipe for Shrimp with Lobster Sauce, which stated, "Here's how the Cantonsese do it." As we can see, this recipe called for lobster, and no pork. It also called for the use of soy sauce.

However, there was a different recipe in the Sarasota Herald-Tribune (FL), July 17, 1949, which is more like the modern versions. It stated "Shrimp with Lobster Sauce" was known to the Chinese as "chow sang har." This is basically Chow Loong Har, aka Lobster Cantonese Style. This recipe does not include any lobster, but called for lean pork, soy sauce, and molasses. Some sources claim New England lobster sauce is different because Chinese cooks in that region used molasses, but we see that at least one recipe in Florida called for molasses.

This is essentially the recipe for the same sauce used in Lobster Cantonese Style, however it lacked ground pork. So, “lobster sauce” may have acquired its name because it was the same sauce as that used in Lobster Cantonese Style. Shrimp was, for unknown reasons, substituted for the lobster.

Now, it would have made sense to refer to this dish as “Shrimp Cantonese Style” rather than call it “Shrimp with Lobster Sauce.” And actually, there were mentions of that exact name, extending back at least to 1938. The Columbus News (NE), December 22, 1938, briefly mentioned that someone’s favorite dish was “Shrimp Cantonese.” The Detroit Free Press (MI), January 30, 1941, mentioned a Detroit chef who made “a better shrimp, Cantonese.” Other references were in the Southwest Wave (CA), September 19, 1946, “Fried Shrimp, Cantonese style” and the Herald-News (NJ), April 4, 1947, “Fragrant Jumbo Shrimp—Cantonese Style.” The Tampa Bay Times (FL), January 3, 1948, noted that a restaurant dinner party served “breaded shrimp Cantonese” while a restaurant ad in the Pike County Dispatch (PA), July 1, 1948, included “Lobster Cantonese” and “Shrimp Cantonese.”

However, it seems that the term Lobster Sauce eventually became the more popular term, so that Shrimp Cantonese became much less common over the years. When the term shrimp with lobster sauce was first used, did customers know that the sauce didn't include any actual lobster? However, it seems like some of the earliest dishes of shrimp with lobster sauce might actually have included some lobsters. The menus probably didn't mentioned whether the dish contained actual lobster or not, and it's possible numerous customers didn't know they were eating minced pork rather than minced lobster. Unfortunately, none of the newspapers during this period addressed this issue.

Lobster prices! How much did these dishes cost in the late 1940s? The Baltimore Sun (MD), July 5, 1947, presented a restaurant ad, noting that their week’s special was a dinner of Lobster Cantonese Style, including soup or appetizer, rice, dessert and drink. The lobsters were shipped directly from Maine. The dish normally cost $2 but was on special for $1.25. In September 1947, that same restaurant ran another special, but only lowered the lobster dish to $1.50.

The New York Post (NY), December 5, 1947, provided a recipe for Shrimp with Lobster Sauce, which stated, "Here's how the Cantonsese do it." As we can see, this recipe called for lobster, and no pork. It also called for the use of soy sauce.

However, there was a different recipe in the Sarasota Herald-Tribune (FL), July 17, 1949, which is more like the modern versions. It stated "Shrimp with Lobster Sauce" was known to the Chinese as "chow sang har." This is basically Chow Loong Har, aka Lobster Cantonese Style. This recipe does not include any lobster, but called for lean pork, soy sauce, and molasses. Some sources claim New England lobster sauce is different because Chinese cooks in that region used molasses, but we see that at least one recipe in Florida called for molasses.

The Tampa Bay Times (FL), April 10, 1949, published a menu for the China Inn noting that Fresh Shrimp with Lobster Sauce cost $2.25 while Fried Whole Lobster Cantonese Style cost $2.50. A very minor difference in price. There was another menu presented in the News-Journal (OH), April 24, 1949, which had a larger difference, with Fried Shrimp with Lobster Sauce for $1.35 and Fried Lobster Cantonese Style for $2.25. And in the Evening Star (D.C.), September 25, 1949, there was a menu that offered Shrimp, Lobster Sauce for $1.50 and Lobster, Cantonese Style for $2.00.

A new name for shrimp with lobster sauce. The Evening Sun (MD), November 8, 1948, published a restaurant ad which referred to shrimp with lobster sauce as Har Loong Woo. The ad also stated their jumbo shrimp had the same sauce as their Lobster Cantonese.

The Los Angeles Mirror (CA), November 9, 1948, explained a bit about the contents of lobster sauce in a review of the Ming Room restaurant. It noted “Canton Shrimp with lobster sauce (garlic, egg, chopped pork, and soy bean).”

Another recipe was presented in the Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph (PA), August 28, 1949, for Shrimps with Lobster Sauce, and the ingredients included: ½ lb. finely ground lean pork, 1 tbsp. minced carrot, 1 tbsp minced celery, 1 tsp. salt, dash pepper, ¼ cup fat or salad oil, 1 tsp salt, dash pepper, 1 clove garlic, 1 cup bouillon, 2 lbs. raw shrimps, 1 egg slightly beaten, 2 tbsps cornstarch, ¼ water, and 2 tbsp minced scallions. This is similar to the prior recipe from the Trenton Evening Times (NJ), April 2, 1942. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle (NY), September 22, 1949, presented a similar recipe for Shrimp with Lobster Sauce, Cantonese.

A variant recipe arose during the 1950s. The Boston Globe, January 22, 1952, published a recipe from one of their readers for Chinese Lobster Sauce. First, you made a mix of salt, pepper, chopped pork, carrot, celery, and scallion or onion. You then fried lobster with the pork, some bouillon, and an egg. Finally, you blended cornstarch, soy sauce, and water, and added it to the sauce.

A cookbook recipe. The Ancestral Recipes of Shen Mei Lon (1954) provided a recipe Chow Loong Har, Lobster Cantonese. This recipe called for lobster, ground pork and soy sauce.

The Boston Sunday Advertiser, December 16, 1956, also provided a recipe for Shrimp with Lobster Sauce, and the ingredients included both light and heavy soy sauce. The Boston Globe (MA), August 19, 1962, had a recipe for Foo-Young-Har-Kow (shrimp with lobster sauce) which used soy sauce and gravy darkener. This would clearly make a darker lobster sauce.

The Chinatown Handy Guide San Francisco (1959), had its own recipe for Shrimp with Lobster Sauce, which didn't call for lobster, but did call for ground pork and soy sauce. This is very similar to the modern version of this dish.

Nowadays, lobster sauce in New England is commonly a brown sauce, while it remains generally white in the rest of the country. Why the difference? I'll address that issue shortly.

A couple explanations were provided for the name of lobster sauce. The Boston Globe, November 29, 1962, published a letter from a reader who stated he was told by a Chinese restaurant owner, of over 30 years, that “lobster sauce never contained lobster. It is called lobster sauce merely because it is usually served over lobster or other sea foods. The trend is now to serve lobster sauce with shrimp.”

And in the Sunday Herald Traveler (MA), May 3, 1970, it noted: “Don’t look for lobster in Shrimp with Lobster Sauce. The sauce is made of ground beef, of all things. The Cantonese use the same sauce for Lobster with Meat Sauce, which may explain the nonsensical name.” I'll also note that the Boston Sunday Herald, April 9, 1967, provided a recipe for Chinese Lobster Sauce that called for the use of a cup of lean raw pork or beef ground fine.

That was the first mention I found of any Lobster Sauce recipe calling for beef. All of the previous recipes called for pork, which makes sense considering the important role of pork in Chinese cuisine. In addition, during the first half of the 20th century, pork was generally cheaper than beef, so it would have been less expensive to use ground pork in lobster sauce. However, in the 1960s, for the first time that century, beef was less expensive than pork, so that probably explains why references during the 1960s also mentioned ground beef as an option in lobster sauce.

Soy sauce made its appearance in Boston recipes for Shrimp with Lobster Sauce but it’s interesting that soy sauce also made an appearance other recipes for Lobster Cantonese Style, and not just in New England. Both the Philadelphia Inquirer (PA), May 2, 1952 and the Chicago Tribune (IL), May 13, 1955, gave recipes for Chow-Loong Har (Cantonese Lobster), and each used soy sauce.

An explanation for the use of soy sauce in these recipes, including lobster sauce, might have been provided by a Chinese chef in New York City, who was discussed in an article in the New York Times, February 3, 1972. The chef indicated that he prepared Lobster Cantonese Style in two ways, one for Chinese customers and one for Americans. Both recipes were provided and there were a number of similarities and differences.

Both recipes included ¼ cup peanut oil, ¼ pound ground pork, 1 one‐and‐one‐quarter‐pound live lobster, ½ teaspoon salt, ⅛ teaspoon MSG (optional) and 1 egg, beaten. Both recipes also included the following ingredients, although the amounts differed: ¼ (vs ½) teaspoon chopped garlic, ½ cup (vs 1 ½) chicken stock, ¼ teaspoon (vs a few drops) sesame oil, and 1 teaspoon (vs 3 teaspoons) cornstarch. The Chinese version also included several ingredients that were not in the American version, such as 1 teaspoon Chinese salted black beans, 3 or 4 slices fresh ginger root, ⅛ teaspoon dark soy sauce, and 1 or 2 sliced scallions.

Thus, lobster sauce which included the use of soy sauce may have been created more for Chinese customers, although it also became popular with other customers as well.

Finally, an intriguing tidbit about lobster sauce. The Canton Repository (OH), July 5, 1971, reported on a national pasta recipe contest, sponsored by the North Dakota State Wheat Commission and National Macaroni and Durum Wheat Institutes, which was open “only to professionals in the quantity food field.” The winning recipe was "Spaghetti with Chinese Lobster Sauce." The recipe called for the use of lobster tails, ground pork, and soy sauce.

Although the exact origins of lobster sauce are still unknown, we know far more than what many other sources have provided. The dish's origins extend back to at least 1898, to Lobster Cantonese Style (also referred to as Chow Loong Har). It's also clear that the price of lobster wasn't a reason for the substitution of shrimp for lobster, as shrimp were more expensive. It's also clear that ground pork was an original ingredient in most lobster sauce recipes, until the 1960s when beef became less expensive than pork. Plus, we may understand better why the lobster sauce in New England is more of a brown sauce, but a white sauce in the rest of the country.

Soy sauce made its appearance in Boston recipes for Shrimp with Lobster Sauce but it’s interesting that soy sauce also made an appearance other recipes for Lobster Cantonese Style, and not just in New England. Both the Philadelphia Inquirer (PA), May 2, 1952 and the Chicago Tribune (IL), May 13, 1955, gave recipes for Chow-Loong Har (Cantonese Lobster), and each used soy sauce.

An explanation for the use of soy sauce in these recipes, including lobster sauce, might have been provided by a Chinese chef in New York City, who was discussed in an article in the New York Times, February 3, 1972. The chef indicated that he prepared Lobster Cantonese Style in two ways, one for Chinese customers and one for Americans. Both recipes were provided and there were a number of similarities and differences.

Both recipes included ¼ cup peanut oil, ¼ pound ground pork, 1 one‐and‐one‐quarter‐pound live lobster, ½ teaspoon salt, ⅛ teaspoon MSG (optional) and 1 egg, beaten. Both recipes also included the following ingredients, although the amounts differed: ¼ (vs ½) teaspoon chopped garlic, ½ cup (vs 1 ½) chicken stock, ¼ teaspoon (vs a few drops) sesame oil, and 1 teaspoon (vs 3 teaspoons) cornstarch. The Chinese version also included several ingredients that were not in the American version, such as 1 teaspoon Chinese salted black beans, 3 or 4 slices fresh ginger root, ⅛ teaspoon dark soy sauce, and 1 or 2 sliced scallions.

Thus, lobster sauce which included the use of soy sauce may have been created more for Chinese customers, although it also became popular with other customers as well.

Finally, an intriguing tidbit about lobster sauce. The Canton Repository (OH), July 5, 1971, reported on a national pasta recipe contest, sponsored by the North Dakota State Wheat Commission and National Macaroni and Durum Wheat Institutes, which was open “only to professionals in the quantity food field.” The winning recipe was "Spaghetti with Chinese Lobster Sauce." The recipe called for the use of lobster tails, ground pork, and soy sauce.

Although the exact origins of lobster sauce are still unknown, we know far more than what many other sources have provided. The dish's origins extend back to at least 1898, to Lobster Cantonese Style (also referred to as Chow Loong Har). It's also clear that the price of lobster wasn't a reason for the substitution of shrimp for lobster, as shrimp were more expensive. It's also clear that ground pork was an original ingredient in most lobster sauce recipes, until the 1960s when beef became less expensive than pork. Plus, we may understand better why the lobster sauce in New England is more of a brown sauce, but a white sauce in the rest of the country.

(September 26, 2025: This article was revised/expanded.)

Friday, October 21, 2022

Vinarjia Čobanković Winery & Ivan Buhac Winery: Sylvaner to Merlot

On one of our days exploring Slavonia, during our tour of Croatia, we visited six wineries, although the last two visits were relatively brief. Both the Vinarija Čobanković Winery and Ivan Buhac Winery produce a significant amount of value or bulk wines, including box wines, primarily for the local market. However, both also produce some excellent, premium wines,

Most of their production is bulk wines, inexpensive wine that is meant to compete with cheap imported wines, often packaged in boxes or plastic. They also produce about 70,000 bottles of premium wine, although nearly all are sold within Croatia. The winery has about 10-11 labels, and their most popular wine is Graševina, although their Pinot Sivi does very well too. In addition, they produce a Sylvaner wine, which helps make them standout in the region. They also make some red wine, although Ivan stated he would like to age their red wines longer.

The 2020 Vinarjia Čobanković Graševina, with a 12.5% ABV, was fermented in stainless steel and then aged for about 6 months in 1100 liter Slavonian oak barrels. It was an easy-drinking wine, pleasant and crisp, with tasty apple notes.

The 2020 Vinarjia Čobanković Pinot Sivi (Pinot Gris), with a 13% ABV, was aged in barrique. It possessed an interesting taste, with a blend of citrus, spice, toast and savory notes.

My favorite wine of the three we tasted was the 2021 Vinarjia Čobanković Silvanac Zeleni (Sylvaner), with a 12% ABV. On the palate, it presented a complex and delicious melange of flavors, including melon, pear, and herbal notes. It was crisp and dry, refreshing and savory, light bodied and with a satisfying finish. Highly recommended.

Back in 1998, the Ivan Buhac Winery was founded by Ivan and his son, Domagoj. Its interesting to note that "Buhac," in Russian roughly translates as a "heavy drinker" or even "alcoholic." They currently have about 27 hectares of vineyards, 20 they own and 7 they lease, and have a capacity of 300K liters, although they only produce about 200K liters. In 2006, they started making red wines, and were also the first to produce a Merlot wine in their region. 60% of their current production is Graševina, while 20% is Merlot.

The 2021 Ivan Buhac Graševina. with a 12% ABV, is an easy drinking, light bodied, fruity and refreshing wine. A fun summer wine, enjoyable on its own. About 70% of the Buhac production is Graševina, and 80% of that production is sold to Zagreb.

The 2021 Ivan Buhac Sauvignon Blanc, with a 11.5% ABV, was light and aromatic, with flavors of lemon, grapefruit and with some mineral notes. Domagoj noted that this grape is difficult to grow, and hard to preserve its aromas, because of the heat of the region.

The 2021 Ivan Buhac Chardonnay, with a 13.% ABV, sees only stainless steel, although Domagoj believes it needs some oak aging. I found the wine to be fresh and bright, crisp and dry, with pleasing apple and mild tropical notes. I think it was very nice without the oak, although it would be interesting to see what a bit of oak might bring to the wine.

The 2019 Ivan Buhac Merlot, with a 14% ABV, is a blend of 85% Merlot and 15% Cabernet Sauvignon. The bottle is twice as heavy as a normal bottle, and that may reflect that this is a big wine, with a dark red color, rich black fruit flavors, dark spice notes, bold tannins, and a lengthy finish. It is a wine for hearty foods, like a juicy steak.

Pictured above is Ivan Čobanković, the oldest son of Petar Čobanković, a former Croatian Minister of Agriculture, Forestry and Water who also worked at Iločki Podrum for a time. Although their family has made wine for many years, mainly for home consumption, the commercial winery wasn't established until 2003. Back then, the family only owned about 4 hecatres of vineyards, as well as 2 hectares of peaches. Now, they own about 100 hectares of vineyards, producing about 300K liters of wine annually.

Most of their production is bulk wines, inexpensive wine that is meant to compete with cheap imported wines, often packaged in boxes or plastic. They also produce about 70,000 bottles of premium wine, although nearly all are sold within Croatia. The winery has about 10-11 labels, and their most popular wine is Graševina, although their Pinot Sivi does very well too. In addition, they produce a Sylvaner wine, which helps make them standout in the region. They also make some red wine, although Ivan stated he would like to age their red wines longer.

The 2020 Vinarjia Čobanković Graševina, with a 12.5% ABV, was fermented in stainless steel and then aged for about 6 months in 1100 liter Slavonian oak barrels. It was an easy-drinking wine, pleasant and crisp, with tasty apple notes.

The 2020 Vinarjia Čobanković Pinot Sivi (Pinot Gris), with a 13% ABV, was aged in barrique. It possessed an interesting taste, with a blend of citrus, spice, toast and savory notes.

My favorite wine of the three we tasted was the 2021 Vinarjia Čobanković Silvanac Zeleni (Sylvaner), with a 12% ABV. On the palate, it presented a complex and delicious melange of flavors, including melon, pear, and herbal notes. It was crisp and dry, refreshing and savory, light bodied and with a satisfying finish. Highly recommended.

Domagoj Buhac, pictured above, took over the reins of the winery in 2007, and acts as winemaker, although his father still works in the vineyard. After visiting his cellar room, we sat in his kitchen to taste some of this premium wines.

The 2021 Ivan Buhac Graševina. with a 12% ABV, is an easy drinking, light bodied, fruity and refreshing wine. A fun summer wine, enjoyable on its own. About 70% of the Buhac production is Graševina, and 80% of that production is sold to Zagreb.

The 2021 Ivan Buhac Sauvignon Blanc, with a 11.5% ABV, was light and aromatic, with flavors of lemon, grapefruit and with some mineral notes. Domagoj noted that this grape is difficult to grow, and hard to preserve its aromas, because of the heat of the region.

The 2021 Ivan Buhac Chardonnay, with a 13.% ABV, sees only stainless steel, although Domagoj believes it needs some oak aging. I found the wine to be fresh and bright, crisp and dry, with pleasing apple and mild tropical notes. I think it was very nice without the oak, although it would be interesting to see what a bit of oak might bring to the wine.

The 2019 Ivan Buhac Merlot, with a 14% ABV, is a blend of 85% Merlot and 15% Cabernet Sauvignon. The bottle is twice as heavy as a normal bottle, and that may reflect that this is a big wine, with a dark red color, rich black fruit flavors, dark spice notes, bold tannins, and a lengthy finish. It is a wine for hearty foods, like a juicy steak.