"

More than 75% of the population of Mexico may be illiterate. Educational methods in Mexico follow more closely cock-fighting, sotol drinking, and the bull ring rather than the "three R's."

--

Omaha Daily Bee, March 26, 1914:

A letter to the editor written by

Wood B. Wright

This racist comment is interesting for one aspect, that it mentions

Sotol drinking rather than

Mezcal or

Tequila. Today, when discussing Mexico, most people would first mention Tequila and then maybe Mezcal. Very few people though would mention or even know about Sotol. However, back in the early 20th century, Sotol was apparently much more dominant in the northern region of Mexico and Americans on the borders were more familiar with it. Sotol has since been eclipsed by Tequila and Mezcal, but it's starting to make a comeback and you should learn more about it.

The

Sotol plant (

Dasylirion wheeleri), also known as the

Desert Spoon, derives its name from the

Nahuatl word “

Tzotolin,” which basically translates as “

palm with long and thin leaves.” It was once thought to be a type of

Agave but it was eventually discovered that it actually is a succulent that belongs in the

Nolinaceae family. Both the Agave and Nolinaceae families fall under the same plant order,

Asparagales, so they are related to a degree. Sotol grows in northern Mexico and ranges into the U.S., primarily in Texas, Arizona and New Mexico.

Indigenous peoples have been using the Sotol plant for thousands of years, for a number of different purposes. They use the strong fibers of the leaves to make cords and weave baskets. The base of the leaf has been used to make a spoon-like utensil, which led to the Sotol being called the Desert Spoon. The core of the plant has been used as a food source, and some peoples also fermented the plant to make alcohol.

Once distillation was introduced to Mexico, people began to distill the Sotol plant, creating an alcoholic spirit that also was named Sotol. Sotol is primarily produced in the northern Mexican regions of

Chihuahua,

Coahuila and

Durango, though it can be found in other Mexican regions as well. In 2004, Mexico granted Sotol a

Designation of Origin (DO) and formed a

Consejo Mexicano de Sotol to regulate its production. Legally, Sotol can only be produced in the states of

Chihuahua,

Coahuila and

Durango. Generally the producers uses wild Sotol plants, which commonly take about fifteen years to mature, and it is said that one plant can produce a single bottle of Sotol.

In

Texas, a new Sotol distillery,

Desert Door, has opened to the public, raising the issue of whether there is a history of Sotol distillation in the U.S. There appears to be some anecdotal evidence, stories passed down from family members, that Sotol might have been illegally distilled, a form of moonshine, in Texas. It certainly seems plausible that it might have occurred but it would be even more interesting if we could find some documentary evidence to support the belief. In addition, there is the question as to whether Sotol was ever commercially produced in the U.S. or not.

A year ago, my continued research found some historic evidence of Texans illegally producing "moonshine" using Sotol. In addition, I've found a legal rationale for why the commercial production of Sotol, as a spirit for consumption, was illegal and thus apparently never occurred in Texas or any other part of the U.S. in the past. The laws were eventually revised, allowing Sotol production to now occur, but during the 19th and much of the 20th century, it was prohibited.

However, additional research has indicated there actually was a single legal distillery in El Paso, Texas, which commercially produced Sotol. The distillery lasted for only a couple years, closing a short time before the start of Prohibition in Texas. There are still questions about this distillery, especially how it was allowed to legally produce Sotol when the Commissioner of the Internal Revenue had previously declared Sotol and Mezcal production to be illegal

One of the earliest documents I found, with substantial information on Sotol, was in

The American Naturalist Vol. 15, No. 11, Nov., 1881, an article titled

"Sotol" by

Dr. V. Harvard, a U.S. Army Surgeon who was stationed at

Fort Abraham Lincoln in

North Dakota. Dr. Harvard noted that the production of Sotol ".

.. is carried on mostly in the Mexican States of Chihuahua, Cohuihuila and Sonora, and sotol mescal is the ordinary alcoholic beverage of the native population. It is precluded in Texas by the high duties laid on this class of industry." Dr. Harvard doesn't indicate that any "sotol mescal" is produced in Texas, or elsewhere in the U.S.

Dr. Harvard then goes into a detailed explanation of "sotol mescal," from its harvest to a description of the heads, noting harvesting is suspended only during the rainy reason, from June to September. He also notes how the heads are baked in circular pits, which are about ten feet deep, before they are pounded into a pulp. This sounds similar in some respects to the production of Mezcal. However, the pulp is then thrown into vats for fermentation, and for a few days, men tread upon the pulp with their feet. That foot-treading generally doesn't occur when making Mezcal. Once fermentation is complete, it is then placed into a still. "

The first liquor obtained, being richer in alcohol and possessing to a higher degree the peculiar aroma of sotol mescal, is considered of better quality."

Dr. Harvard provides some information on the pricing of "sotol mescal" too. "

A vinata in good running order will turn out a Mexican barrel a day (about twenty-eight gallons), sold at an average price of fifteen dollars, and retailing for thirty or forty centsaquart." He also is appreciative of its taste, "

Sotol mescal is a pure, wholesome alcoholic drink; if the best brand be kept long enough to lose its sharp edge, it compares favorably with good whisky;.." And another benefit is "

On account of its cheapness and characteristic taste, mescal is very seldom adulterated." This is a fascinating article and you should read it for even more information on Sotol.

In some subsequent written references, Sotol in Texas and New Mexico is mentioned as animal feed, with no reference to distillation. A

Colorado newspaper,

Walsenburg World, June 12, 1892, wrote that in the Pacos river valley of Texas, they are using a "

peculiar" sheep feed called Sotol, noting that men with axes must first cut open the Sotol heads and that the sheep are quite fond of the Sotol.

The

Santa Fe Daily New Mexican, April 02, 1895, in an article titled

"Live Stock Interests," wrote "

Attention is now being directed to the nutritive and fattening qualities of sotol, a vegetable growth of the cacti species. Sotol is said by stockmen, who have closely studied its virtues as a stock food, to furnish both feed and water, as it contains sufficient moisture supply stock for long periods without water. Sheep readily fatten on it while cattle and horses take to it as they do to grain. It is not available for sheep unless burst open with an ax." So we see Sotol being used as feed for sheep, cattle and horses, but there isn't any mention that anyone locally is distilling it into alcohol.

There are a number of other newspaper articles during this time frame which discuss feeding sotol to animals, especially sheep, and I haven't added many of them as the information would be duplicative of what I've already mentioned. In none of those articles will you find references to Texans distilling Sotol alcohol.

Mezcal distilleries in Texas? The

Laredo Times, May 5, 1903, published an article,

Mezcal And This Country, subtitled

Why It Can Not Be Distilled In The United States. The article was in response to a question as why no one had ever started a Mezcal distillery, using the abundant maguey that grew in the U.S. Beyond its connection of Mezcal, the answer to this question has important ramifications concernng the production of Sotol, providing a definitive explanation for why no one could commercially produce Sotol liquor at that time.

The answer was provided by the law, in two related statutes.

Section 3248 of the

Revised Statutes of the U.S. defined "

distilled spirits" as "

spirits, alcohol, and alcoholic spirit, to be that substance known as ethyl alcohol, hydrated oxide of ethyl, or spirit of wine, which is produced by the fermentation of grain, starch, molasses or sugar, including all dilutions and mixtures of this substance."

Section 3255 of the

Revised Statutes then allowed the Commissioner of the Internal Revenue to exempt a specific list of fruits, including apples, peaches, grapes, pears, pineapples, oranges, apricots, berries, prunes, figs, and cherries, used to make brandy, from the regulations of the manufacturing of spirits.

Based on these two Sections, the Commissioner had ruled that "

the articles and fruits mentioned in the statues above quoted are the only ones which can be used for the purpose of distilling alcoholic liquors..." Because Sotol and Maguey were not specifically mentioned in these statues, then neither could be legally distilled to produce alcohol. Thus, no one could operate a legal Sotol distillery in Texas, or anywhere else in the U.S. Quite a definitive answer.

I've been unable to find any information that the Commissioner of the IRS changed his decision prior to Prohibition.

The article also briefly mentioned that about two years ago, a man established an illegal distillery in West Texas, and had produced about 600 gallons of "

mezcal" from Sotol. However, the government somehow learned of the operation, and subsequently seized and destroyed the still and illegal Sotol "moonshine." So, we also see evidence of illegal distillation in Texas.

Subsequent references to Sotol being distilled for alcohol aren't quite what you think.

The Brownsville Daily Herald, October 12, 1906, in an article titled "

And Ozona Is Advertised," reports that: "

Another gold mine has been discovered in Texas, namely, the vast quantities of alcohol contained in the sotol bush. At Ozone, in Crockett county, the light and ice company is making its own fuel from the sotol and this same company proposes to supply fuel for power to all the surrounding country from its distilling plant." Again, there is no mention that anyone in Texas was distilling Sotol for alcohol consumption.

There were additional references to the plans to use Sotol for fuel.

The Jimplecute, October 13, 1906 mentions "

San Antonio: John Young of Ozona, who is at the head of the company that proposes to distill denatured alcohol known at (sic) "sotol," is in this city and has shed some new light on the proposed enterprise. He says that sotol plant has somewhat the appearance of a cabbage and grows in great abundance all over West Texas. For many years the Mexicans have manufactured mescal from the plant, producing a good grade of alcohol." Though it mentions Mexicans making alcohol from Sotol, there continued to be a lack of mention of any Texans doing the same.

The San Angelo Press, October 18, 1906 added more detail, stating that the denatured alcohol would replace fuel oil in machinery plants, also stating that: "

Other good uses have been made of sotol, however. Sheepmen in the sotol section have long utilized it as the chief food during the winter for their flocks." And once again, despite referencing other uses for Sotol, there wasn't any mention of Texans making alcohol from Sotol.

Another such reference was in the

El Paso Herald, June 18, 1907. which printed that "

Within six months there will be completed and in operation in El Paso a plant for the extraction of alcohol, ether and fiber from all forms of the cactus plant. This concern will be known as the El Paso Chemical and Fiber Works..." The plant, which was planned to be in an adobe building, would cost $20,000 and have a capacity of 20 gallons a day. "

The alcohol will be denatured alcohol, therefore usable for fuel." Though the article claimed this would be the first plant of its kind in the U.S., the earlier references provided here seemed to indicate there was at least one other plant prior to this planned El Paso plant.

As for the continued use of Sotol as feed, the

Albuquerque Evening Citizen, July 03, 1907 published an article,

Alfalfa versus Sotol for Cattle, discussing a report prepared by a New Mexico agricultural experiment station that conducted a study of the use of Alfalfa vs Sotol. Though they found that Sotol was generally cheaper than Alfalfa, commonly by as much as half, they also concluded that Alfalfa was generally better nutritionally for the animals unless additional ingredients were added to the Sotol feed. In the end, it came down to how inexpensive a farmer could obtain Sotol and the other ingredients as compared to Alfalfa.

Returning to the El Paso plant, the

El Paso Herald, August 12, 1907, indicated the factory would be constructed on three blocks in the Grandview Addition. The plans for the building hadn't been completed yet and construction wouldn't begin until those plans were complete. There was a follow-up in the

El Paso Herald, October 30, 1907, indicating that the main building, the distillery, was nearly completed. A four-room cottage and stable had also been completed, and they were still working on finishing the fiber building and a bonded warehouse. The plant was supposed to begin operation on January 1, 1908, with a capacity of 1,000 gallons of alcohol, far greater than originally planned.

Plans didn't work out as expected. The

El Paso Herald, May 1, 1908, reported that the factory hadn't opened yet, awaiting government authorization for their alcohol distillery, but would open their fiber factory on May 4. Then, the

El Paso Herald, July 29, 1908, discussed the imminent start of the distillery, noting that they had already conducted a test run.

A few changes were made to the process due to findings from that test. They also learned that the "

heart of the cactus...after the fibrous blades had been cut off, was a juicy pulp easily converted into alcohol of a very superior quality." In addition, they decided that they would produce only about 500 gallons per day, finding it more beneficial than trying to reach 1,000 gallons. On August 26, 1908, it was announced that the plant needed up to another two weeks before it could finally start production.

Some general information about Sotol, and a short bit about the proposed El Paso plant, was provided in

The Buffalo Sunday Morning News, Sept. 27, 1908. The article first mentioned how there are millions of acres of Sotol plants in the mountainous area of Western Texas, and that it's said not to grow anywhere else in the U.S. Second, it stated that the Sotol plant can yield a percentage of alcohol greater than any other plant. Third, it mentioned how Congress authorized the construction of a plant to produce denatured alcohol from Sotol, which refers to the El Paso Chemical and Fiber Company.

Fourth, and most interesting, there was a brief historical item, mentioning that when the Spanish came to this area, they found that the "

Pueblo and other Indian tribes" already knew of the alcoholic potential of Sotol. They were already using primitive stills to distill a "

fiery white liquor." It was also mentioned that Sotol was still a favorite drink of the Mexicans, and that "

American cowboys" on the border ranches were familiar with Sotol as well. For example, drinking Sotol was considered one part of the initiation rituals for "

tenderfoots" on these ranches. However, there wasn't any mention that anyone in Texas was distilling Sotol.

There were more problems at the El Paso plant in October. The

El Paso Herald, October 12, 1908, reported that there had been difficulty in getting alcohol from the product, although they weren't having any problems getting tequila. They wanted to bring in a master distiller for assistance. The

November 16, 1908 issue noted the company was still having problems getting denatured alcohol from the yucca plant and they would run the plant for 90 days under the auspices of a distillery expert. Obviously, the plant had significant problems and

The Houston Post, October 1909, noted the El Paso Chemical company had gone into receivership. It apparently never commercially produced Sotol for drinking purposes, and even had extreme difficulty in making denatured alcohol for fuel.

The Bulletin of Agricultural Experiment Station, New Mexico College of Agriculture and Mechanic Arts, Issues 72, August 1909, printed an extended article about denatured alcohol, as well as discussing the El Paso Chemical plant. "

In this investigation we will also include a study of the alcohol obtainable from the sotol and lechuguilla, the two plants that the El Paso Chemical and Fiber Company made an unsuccessful attempt to ferment for alcohol production.

About a year ago this company erected a factory in El Paso. Texas, at a cost of something over $40,000 for the production of denatured alcohol, but for very evident reasons the plant was in operation only a short time."

The article continued, "

El Paso plant was able to produce small quantities of fermentable sugar, would seem to indicate that the high steam pressure of the autoclave must have hydrolyzed some sugars without the presence of any mineral acid. It was not sufficient, however, to place the production of alcohol from these plants on an economical basis, and the factory soon closed its doors." It is clear this distillery was only trying to produce denatured alcohol, and even that was ultimately unsuccessful.

During this time period, smuggling Sotol across the border, from Mexico into the U.S., was a problem and there were multiple references in various newspapers about people being caught smuggling. For example, in the

El Paso Herald, August 04, 1910, there was a report of a Mexican smuggler trying to discard his contraband Sotol, "

the Mexican booze," before he was apprehended by the border authorities. In none of these references was there any indication that Americans were distilling their own Sotol.

In the

Bryan Daily Eagle And Pilot, May 08, 1911 there was a brief mention of Sotol: "

Then there are the sotol and the maguey and other desert plants, which the Mexican well knows how to convert into either food or drink." Once again, Sotol distillation seemed restricted to Mexico and there was no mention of it occurring in the U.S.

Some companies were starting to use Maguey and Sotol to produce alcohol, although not for comsumption. The

News Journal (DE), December 20, 1913, reported that the

Cactus Alcohol Co., incorporated in Delaware with a capital stock of $250,000, was formed to engage in the extraction or distillation of alcohol and other products from cactus.

As a follow-up, the

El Paso Herald Post (TX), March 16, 1914, indicated, “

The Cactus Alcohol company will be in operation in El Paso in 60 days, tuning out denatured and the regular kind of alcohol, and fiber articles of various kinds.”

Dr. Frank T. Thatcher, of El Paso, was the president and general manager while

L.M. Stiles, also of El Paso, was the vice-president and treasurer. Some of the other investors in this corporation were from outside of El Paso, although no other details on them was provided.

The Cactus Alcohol Co. didn't do well, so it was reorganized, becoming a different company, with the objective of producing spirits for public consumption. The

Austin American-Statesman (TX), April 22, 1916, reported that the

Cactus Fiber and Reduction Company of El Paso has been incorporated, with a capital stock of $18,500. The incorporators included:

Gunther R. Lessing, Oscar L. Bowen, and

Jose D. Madero. And then the

San Antonio Light, November 10, 1916, noted the corporation had increased its capital from $18,500 to $30,000.

The company seems to have started selling their spirits in early 1917, and the first advertisement I found for it was in the

El Paso Times (TX), February 9, 1917. The ad mentioned it was for "

Cactus Mezcal," distilled in El Paso under Government inspection. It also mentioned that Mezcal is "

a preventative and remedy for tuberculosis and kidney troubles." In addition, the ad stated it was "

Genuine Mexican Mezcal." The company's office was at 511 East San Antonio Street and that the distillery was located at the Grandview Addition, Blocks 112-114. Based on this ad, it would seem the company was only producing Mezcal from agave, but that turned out not to be the case.

The Spanish edition of the

El Paso Times (TX), February 9, 1917, presented a similar advertisement, except there were some intriguing differences as well. Rather than a heading of Cactus Mezcal, this ad was headed by

Mezcales Mexicanos. The ad also indicated they had managed to produce for the first time in the U.S. a Mexican Mezcal. Curiously, their first label was "

Sotol Fino," which was said to have an exquisite taste, delicate aroma, and unbeatable quality and purity.

However, there appears to be some confusion as to whether Mezcal and Sotol were two different spirits. Were they actually making Mezcal or Sotol? With the Sotol plant on the label, and the words "Sotol Fino" on the bottle neck, it seems that they were producing Sotol and not Mezcal. Why didn't the English advertisement mention Sotol?

Finally, the Spanish ad mentioned that in the future, the company would be producing Tequila and Bacanora, but they would be importing the maguey from Mexico.

A better photograph of the bottle and labels can be found in

El Paso Prescription Bottles, the Drug Stores That Used Them and Other Non-Beverage Bottles (2015) by

Bill Lockhart, a privately published work. In

Chapter 8, p.191, there is a color photograph of the labels from an Ebay listing. It clearly shows a Sotol plant in the lower right of the main label, along with a Mexican flag, eagle and medal. The top label states, "

Sotol Fino."

The

El Paso Times (TX), March 6, 1917, presented a brief ad for the company, stating: “

America First. Try ‘Mezcal Mexicano.’ Not Mexican stuff, but real, genuine ‘Mezcal,’ manufactured in America. Cactus Fiber & Reduction Co., El Paso, Tex.”

The

El Paso Times (TX), March 6, 1917, also had another ad, where the Cactus Fiber & Reduction Co., offered to Cattlemen to clean their pastures and grazing fields of all "

Agane Cactus (Maguey)," which gives them no benefit and can hurt their cattle. So, if the company was acquiring all this Maguey, were they then also making Mezcal, and not just Sotol?

There was another ad in the

El Paso Times (TX), March 8, 1917, which referred to the product as "

new American Brandy. Bottled under bond in America." It also stated it was available in hotels, cafes and "

in the better places." The Spanish edition of this issue was similar, but noted it was produced from the finest Sotol.

A Spanish ad in the

La Prensa, April 3, 1917, noted that the Mezcal Mexicano was the "

salvation" of those afflicted with tuberculosis. The first ad of the Cactus Fiber & Reduction Co. had also mentioned how it helped against this disease. The ad also stated, “

Este elixir de la vida aleja para siempre la turberculosis, los resfrios, toses, etc" which can be translated as "

This elixir of life forever drives away turberculosis, colds, coughs, etc." We also see that this spirit had ranged beyond El Paso and was now available in San Antonio as well.

Sotol cocktails? The

El Paso Times (TX), May 6, 1917, had an ad for

Mezcal Fizz, sold at all saloons, and using the spirit from Cactus Fiber & Reduction Co. Even though it's called a Mezcal Fizz, it would actually be a Sotol Fizz. And this might be the first reference to a Sotol cocktail in the U.S.

Another Sotol cocktail. In

El Paso Times (TX), May 13, 1917, there was a similar ad but for a Mezcal Rickey, which again is really a Sotol Rickey.

The

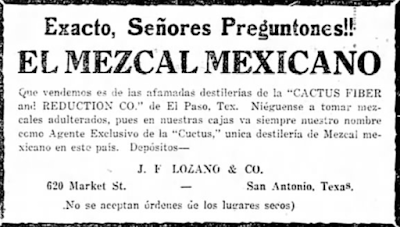

La Prensa (TX), May 27, 1917, printed another advertisement, from

J.F. Lozano & Co., the exclusive agent for the Cactus Fiber & Reduction Co., which was said to be the only Mexican Mezcal distillery in the U.S.

These advertisements continued to appear in the newspapers through June 1917, but vanished after that month. Did the company stop selling their Sotol? The company was apparently still in business as there were a couple mentions of it in August 1917. The

El Paso Herald, August 2, 1917, briefly noted that the Cactus Fiber and Reduction Co. had been granted a petition for a sewer connection. The

El Paso Herald, August 23, 1917, had a Help Wanted ad for an “Expert boiler erector” for the Cactus Fiber Co.

The El Paso Times, November 13, 1918, then reported that the Cactus Fiber & Reduction Co. would "shortly liquidate its business” and offer for sale its location and factory.

The resolution of the fate of the company was detailed in the El Paso Times, November 21, 1920. The article stated that “.., the plant once built in El Paso for extracting the sap of the cactus for commercial purposes is being moved back to its native land—Mexico.” When the Cactus Alcohol company was reorganized, becoming the Cactus Fiber & Reduction company, Francisco Arredondo Cepada of Mexico became one of its vice presidents. It was noted that, “With Mexican initiative and exclusive knowledge of vintage and its processes of manufacture, the industry has persistently failed to pay dividends in El Paso, so that Cepada is having the machinery shipped to his properties in Cuetro Cienegas, Coahuila.” In Mexico, they planned to use the machinery to distill their own maguey spirits.

An article in

The Houston Post, March 26, 1917, discussed moonshine operations in Texas. "

Of course there have been in Texas the moonshine distilleries which were so common in more eastern states...Be that as it may, distilleries, legal or illegal, have never been a success in this state." This section only mentioned Texan's difficulties in making whiskey from corn.

The article then printed, "

At this time only one distillery of any kind, so far as known to the officials, is operating in Texas. This prosperous concern is located in El Paso. It supplies to the Mexicans of that city and contiguous territory their natural drink, mescal, which is distilled from sotol." This distillery was not named, and no other identifying information was provided.

Previously, I thought this article might have been in error, but the additional research clearly indicates they had to be referring to the Cactus Fiber & Reduction Co. However, it doesn't seem the company was actually prosperous, but this article seems to make it clear they were producing sotol, although it was also referred to as mescal still.

Back to Sotol as animal feed. The use of Sotol for animal feed took a technological step forward as reported in

El Paso Herald, July 04, 1917. A new company was formed in El Paso,

Sotol Products, to produce feed for livestock derived form the Sotol plant. The company had a new patented process which produced a nutritious Sotol molasses. This molasses was then combined with the pith of the Sotol as well as some Alfalfa or other vegetable material. This livestock feed could be sold at "

an extraordinary low price."

In a follow-up, in

El Paso Herald, July 27, 1918, there was an advertisement for this new Sotol animal feed. The "

Sotol Molasses Mixed Feed" contained a blend of 25% Alfalfa Meal, 25% Ground Sotol Plant, and 40% Sotol Molasses. There was then a breakdown touching on the feed's Fats, Protein, Nitrogen Free Extract & Crude Fiber and comparing them to beet pulp, showing that the molasses mixed feed was better for livestock. And the advertisement also stressed the low cost of this product.

Finally, I've heard some claim that there might have been a Sotol distillery in

New Mexico, but that seems to be based on an incomplete information. The

El Paso Times, September 24, 1923, detailed an account of a couple murders, and some other news accounts of this incident were much less detailed. Those shorter reports seemed to indicate one of the bodies was found near a Sotol distillery south of Columbus, New Mexico. That is factual, except that actually it was far enough south that it occurred in Mexico, not New Mexico.

The El Paso article noted that Holly Herring's body was found in a hollow near a Sotol distillery, but the article stated it was located on the south side of the

Ojo Federico ranch, which is in Mexico. This was confirmed as the authorities in the U.S. had to obtain the permission of Mexico to retrieve the body and then it to the U.S. The Sotol distillery was thus located in the Chihuahua region of Mexico, and not in New Mexico.

There is limited evidence of Texans making illegal Sotol "moonshine," as well as smuggling over the border. Sotol was used to produce denatured alcohol for fuel, though even that production was relatively small, as the companies ran into an assortment of problems producing it. There was also a single legal Sotol distillery in El Paso, which primarily produced Sotol during 1917. How it got around the law making Mezcal and Sotol distilleries illegal in the U.S. remains a mystery. Maybe new research will one day resolve that matter.

As more Mexican Sotol becomes available in the U.S. market, I recommend you seek it out. You'll find some local Mexican restaurants may carry one or two Sotol. Be adventurous and enjoy a new spirit!

"

There is some resemblance between the cabbage and sotol, but there is no reason to conclude that cabbage beer is anything like mescal, one drop of which, it has been said, will make a rabbit go out and hunt a fight with a bulldog."

--Bryan Daily Eagle And Pilot, August 26, 1911

(

Please be advised that my original article on Sotol was first published in 2017, but has since been revised and expanded a few times, due to additional research. This latest edition owes a big debt of gratitude to Steve Swinnea for pointing me toward the Cactus Fiber & Reduction Co., a legal distillery in Texas which produced Sotol.)