Curries and rice. Vindaloo to Tikka Masala. Naan to Poori. With its many regional cuisines, the food of

India is diverse and delicious. There are roughly 6,000 Indian restaurants in the U.S., a relatively low number considering that Indians constitute the second largest population of Asian-Americans in the U.S. Compare this to the approximately 45,000 Chinese restaurants in the U.S.

What was the first Indian restaurant in the U.S.?

That question spurred on my research to try to discern the answer. A surface examination indicated that the alleged first Indian restaurant was the Ceylon India Inn, established in New York City around 1913-1915. However, on a deeper research dive, I found a different answer, that the first Indian restaurant was actually the Omar Khayyam, in New York City, which was likely founded in December 1901.

The Omar Khayyam restaurant lasted for about only six months, but its chef, Prince Ranji Smile, who was likely also the first Indian chef in the U.S., continued to cook East-Indian dishes in the U.S. for over twenty-five years. Prince Ranji Smile was a fascinating character, an extremely talented chef but also a self-promoter and showman who played loose with the truth. Some people have considered him to be a confidence man, and there may be an element of truth to that designation, although he generally didn't try to fleece people of their money.

As Ranji embellished, and even lied about his life, it’s difficult to determine the entire truth about this man. We cannot even be sure of his birth name or date of birth, although there is some reasoned speculation. At times, Ranji claimed to be Indian royalty, although he also denied that claim at other times. Ranji offered contradictory stories about his background and family, failing to provide evidence or proof to support his claims.

What doesn’t seem to be in dispute was his culinary skill, as he worked for some of the best hotels in London and the U.S., and maybe elsewhere as well. His culinary career in London started when he was young, approximately when he was 21 years old, although even that age is suspect. However, how he acquired those culinary skills remains a question. Some was undoubtedly due to natural talent, but he likely received some type of culinary training as well.

Let’s explore what’s known, and unknown, about the life of Prince Ranji Smile, and try to better understand his legacy.

According to Eight Flavors: The Untold Story of American Cuisine (2016) by Sarah Lohman, “On

May 11, 1879, …, Ranji Smile was born near Karachi, India, possibly in the province of Balochistan.” In addition, “Smile’s real name might have been Ranji Ismaili, pronounced “Iss-smile-ee.” However, various newspapers and magazines contradict these matters, complicated by Ranji himself providing contradictory information about himself.

For example, let’s address his age. The Harper’s Bazaar, October 28, 1899, noted Ranji had first come to London, about five years ago, which would have made it 1894, and when Ranji was twenty-one years old. However, by Lohman’s date of birth, Ranji would have been only 15 years old in 1894, which is improbable. The Philadelphia Inquirer (PA), November 10, 1901, later stated that Ranji was currently 24 years old, but by Lohman’s date of birth, he would have been 22 years old.

Six years later, the St. Louis Post-Dispatch (MO), December 2, 1907, claimed that Ranji was 28 years old, which coincided with Lohman’s date of birth. And then The Evening World (NY), August 6, 1912, noted that two years previously, in 1910, Ranji was allegedly 30 years old, although he also claimed to only be 30 years old in 1912 as well. By Lohman’s date of birth, he would have been 31 years old in 1910. In the end, Ranji's date of birth is speculative.

As for Ranji’s birthplace, a couple sources claim he was from Karachi, but other sources claim he was from Baluchistan, once a region in India but which is now part of Pakistan. Around 1901, there were rumors that Ranji was an actual “prince,” but in the Providence Daily Journal (RI), November 8, 1901, Ranji noted that his first name was actually “Prince,” and it wasn’t a title of royalty.

However, around 1904, Ranji started to claim he was actually royalty, one of the sons of the Ameer of Baluchistan. Different accounts placed him as the third, fourth or fifth son of the Ameer (with the fifth being the most common attribution). His oldest brother was currently the Ameer as their father had apparently died over 20 years ago. Although most newspapers seemed to accept Ranji's claim of royalty, a few newspapers noted that there was no evidence that Ranji was actually royalty.

Merchant, not Amber! The Providence Daily Journal (RI), November 8, 1901, mentioned that Ranji’s father was a merchant of Sidhpoor, “a self-made man,” and not royalty. Ranji claimed, “My father travelled over India selling goods and took me and my brother with him.” He then mentioned that he eventually ran away from home, joining a ship and becoming their cook. The Brantford Daily Expositor (Ontario, Canada), November 8, 1901, added that Ranji had worked as a cook on a ship of the Peninsular & Oriental line of London. It's possible this was Ranji first learned to cook when he was a teenager.

However, in the Philadelphia Inquirer (PA), October 13, 1904, Ranji claimed “My father took me around for seven years to study the best cooking in the world and soon I could surpass all the chefs because I could originate.” He then alleged that his first cooking job was for Sultan Mulik, who would not let Ranji resign his position or leave his employ. So, Ranji fled for his life, but it was also said that, “A few weeks later the Prince received a token of forgiveness from the Sultan. This took the form of a letter written on gold tablets, and the Prince now wears this letter as an ornament upon his turban.”

Fifteen years later, the Variety, January 10, 1919, reported that “… Prince Ranji is the portion given him when born, by his royal father, a Rajah of India, and the wealthiest noble of Punjab, a province at the foothills of the Baluchistan mountains.” Then they posted quite a wild story. Ranji allegedly “… left his home when a boy, wandering into the hills, becoming lost and finally picked up by bandits, who held him for a ransom approximating $100,000 in American money, when learning who he was. Hearing of the large forces sent by the Rajah to recover his son, the bandits turned the boy adrift and fled. Having carried the Prince by this time far into the mountains, the youngster led a wild life for several years, until at about 16 he was taken in by the colonel of an English regiment, sent to Burmah; but having forgotten his name and residence while the fears of the jungle were forced upon him in his wanderings, the Prince could furnish no information regarding himself. The English at Burmah developed a fondness for the boy and sent him to Calcutta. He eventually left there and traveled until 22, when reaching London. Here some folks interested themselves in him and through their efforts memory of his home was restored; illustrations of the scenes and the mention of his family name bringing back his early youth. Writing to his father, who had spent over $2,000,000 attempting to locate his lost son, the father replied, saying he believed the letter to have been written by an imposter. It embittered the Prince, who has never returned to India.”

The article further noted that Ranji is still terrorized by a memory of awakening one night in the jungle to find a 10-foot tiger softly pawing his face, although the tiger didn’t harm him. “The Prince said he had not been eating regularly in the jungle and the animal might have decided he was indigestible.”

Ranji's actual background is lost within the contradictory stories he offered over the years, so let's try to establish some facts of his life, in a rough chronological order, although noting that some of this information is speculation and others may be false claims by Ranji himself.

At some point, maybe around 1896 (although it might have even been a year or two earlier), when Ranji was 17-21 years old, he traveled to London. Ranji might have worked at a few hotels before being hired by the

Hotel Cecil, a grand hotel which opened in 1896. The Cecil was supposed to be the largest hotel in Europe, with over 800 rooms, and its dining room could seat over 600 people. Ranji’s culinary skills must have been impressive for him to secure a position at such a high-end hotel.

Although Ranji was not named, it’s clear that he was the curry chef described in an article in

The Pall Mall Gazette (England), March 29, 1897. There's no evidence that the Cecil had a different curry cook than Ranji at this time. The article was written by a famous gourmet,

Lieutenant Colonel Newnham Davis, who wrote the book “

London Dinners and Diners.”

Davis described a dinner he enjoyed at the Hotel Cecil with one of his uncles, known as the Nabob, “—so-called by us because he spent many years in the gorgeous East—." The Nabob also “affects the belief that there is no good curry to be had outside the portals of his club, the East India;..” The writer wanted to introduce the Nabob to the curries available at Hotel Cecil.

Their multi-course dinner included numerous French dishes, from Filet de sole a la Garbure to Mousse de Foi Gras et Jambon au Champagne. It also included “Curry a l’Indienne” and “Bombay Duck.” The writer and Nabob got to meet the curry cook, who was “clothed in white samite, and with his turban neatly rolled,…” The Nabob, in fluent Hindustani, cross-examined the cook as to the art of curry-making, and found his answers apparently satisfactory.

The curry then arrived at their table. “Then came the dish of the evening, a tender spring-chicken for the foundation of the curry, and all the accessories, Bombay duck, that crumpled in our fingers to dust, paprika cakes, thinner than a sheet of notepaper, and chutnees galore to add to the savoury mess. It was a genuine Indian curry, and the curry cook, his hands joined in the attitude of polite deference, stood and watched rather anxiously the Nabob take his first mouthful.” The Nabob then stated, “Er, um, yes, good… Good, decidedly. I don’t say as good as we get it at the club but decidedly good.” Davis added that the Nabob “was bound to say this,” that he wouldn’t admit that his own club’s curry might not be as good as the one at the Hotel Cecil.

Ranji probably worked at the Hotel Cecil for about 12-18 months, and then got a job as a curry cook at the Savoy, another luxury hotel in London. Why he left the Hotel Cecil is unknown. He might have worked at the Savoy for about a year, before leaving London and traveling to New York City to work at Sherry’s. The famous restaurateur, Louis Sherry, owner of Sherry's in New York City, had traveled to London, met Ranji, enjoyed his cuisine, and convinced him to come to the U.S. and cook at his restaurant.

An intriguing article later appeared in the Philadelphia Inquirer (PA), December 2, 1901, providing the reminisces from someone, M. MacM, 3rd, who had known Ranji when he worked at the Hotel Cecil. The writer met Ranji in early 1897, but claimed that his name wasn’t “Ranji” or “Smile” when they first met, although he failed to provide his actual name. He very much enjoyed Ranji's curries, and stated he was "an undoubted artist at the game of curry building." Ranji had been provided his own section of the kitchen to make his curries, which he could make from mild to very hot. “In fact he very often combined the functions of the physician with those of the chef, and frequently made cures which were remarkable.” It was also noted that while he worked at Cecil, he was smooth faced, although he would later acquire a beard and mustache.

The writer alleged that he was the first person who started called the curry cook “

Ranji,” as he resembled a famous Indian cricketeer who was popularly called Ranji. Others soon started calling him Ranji as well, and the moniker stuck. The writer also stated that Ranji acquired the name “

Smiler” from Lieutenant Colonel Newnham Davis, who I mentioned above, sometime while he worked at either Cecil or the Savoy.

In

London Dinners and Diners (1899) by

Lieutenant Colonel Newnham Davis, he described a visit to the Savoy where he met Smiler, the curry cook. “

Because I talk a little bad Hindustani, Smiler has taken me under his protection, and thinks that I should not go to the Savoy for any other purpose than to eat his curries.”

The

Buffalo Courier (NY), October 15, 1899, mentioned that Ranji Smile (pictured above), familiarly called “

Joe,” was the first Indian chef in the U.S. He had arrived a few weeks ago, and was working at Sherry’s Fifth Avenue restaurant. Louis Sherry had opened his fine restaurant, Sherry's, in 1898, at Forty-Fourth Street and Fifth Avenue.

The writer noted, “

The fancy for curries, which is the foundation of all India dishes, seems to have taken possession of everyone who has eaten of them.” Commenting on Ranji, he also wrote, “

He enjoys posing for the photographer and thinks himself handsome.” Finally, he quoted Ranji as stating, “

If the women of American will but eat the food I prepare, they will be more beautiful than they as yet imagine. The eye will grow lustrous, the complexion will be yet so lovely and the figure like unto those of our beautiful Indian women.”

The

Los Angeles Times (CA), October 15, 1899 ran a similar article as the Buffalo Courier, but added additional information, including a multi-course East-Indian menu that you could enjoy at Sherry’s. Ranji stated, “

This…is the typical dinner as to the number of courses that ladies in the better stations of life would have in India.” He continued, “

So many ladies are fearful of my preparations, thinking that everything must be very hot and peppery. This is not so of India cooking. All things must be so nicely even, and such care as to smoothness, that it will be of so pleasant a taste they can but ask for more.”

Then Ranji provided some specific culinary advice. “

It is a mistake to boil curries. They should simmer gently and not lose their flavor.” In addition, “

Now, do not boil the rice. Cleanse it, using three times as much water in boiling as there is rice, and never stir it, and then it all comes out like so many separate snowflakes.” As for Ranji himself, it was said, “

Joe makes all his own curry powders and pastes, and makes them so they suit the palates of different nationalities. Just how he does this it is difficult to say, as he follows no special rules, except the spontaneous inspiration of his own head.”

Finally, Ranji stated, “

The reason Americans do not succeed, as a rule, with curries, which form such a background of India cooking, is that they are always in too much of a rush, and they curry everything alike; for to curry a chicken the same as a piece of fish, or a piece of beer, trouble is bound to arise, and, in disgust, the cook layers it onto the curry.”

This article would be reprinted across the country, in newspapers in many other states, including Georgia, Idaho, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Massachusetts, Michigan, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, Texas, Utah, Washington D.C., and Wisconsin. This would probably be the first exposure that many Americans had to an Indian chef, and may have enticed them to seek out Indian recipes to replicate at home.

An article in

Harper’s Bazaar, October 28, 1899, offered information on how Ranji allegedly acquired his culinary skills. He “

… served his apprenticeship in his native town of Karachi, and afterwards in the large hotels of Calcutta and Bombay. When he felt that he was competent to stand as an exponent of the best Eastern cooking, he made a tour of the world, preparing East-Indian dinners for the dignitaries of many cities.” The initial comments, about his apprenticeship and work at Indian hotels seems plausible. However, a world tour is more suspect, and isn’t supported by any other references.

Next, “

He took up his abode in London, about five years ago, when he was twenty-one. At the Hotel Cecil, and afterward at the Savoy, at clubs and residences, he served the aristocracy of England, and in several instances members of the royal family.” Ranji’s age is also suspect, especially if you accept Lohman’s proposed date of birth of May 11, 1879.

The Harper’s Bazaar article then continued, “

Among these the rice, the chief food of India, has perhaps the place of honor. Ranji gives it the superlative degree of excellent that might be expected from the most celebrated of Eastern cooks,…” The rice was then described, “

…the silver platter upon which is heaped the snowy mound. Over the plates of the guests he lightly sprinkles the grains, each being noticeably large and white, and so dry as to fall separately.” Ranji imported the rice from India, because he felt the local rice was more or less broken, or too small and yellow for him.

Once a guest received their rice, they were asked whether they desired mild or hot curry, noting “

the golden brown of the sauce of the curry of chicken, or lobster, or veal, or whatever it may be,..” Accompanying the dish was “

the Indian biscuit—biscuit as large as a dinner plate and as light and thin as paper….They are made of little yellow pease ground up, fresh cocoa milk, the yellow of eggs, and a little flour mixed into a dough and rolled very thin. The dough is cut into large round pieces, which are dropped into a kettle of boiling butter. Ranji withdraws them in an instant, crumpled and twisted, rich brown in color, and of a brittleness that causes them to break at a touch.” Overall, “

He regards his work as an art, and has the enthusiastic artist manner and the deft artistic touch.”

It was later said that Ranji left Sherry’s restaurant around May 6, 1900, after having worked there for only about seven months. Soon after leaving Sherry’s, Ranji departed from the U.S. and headed back to India. So, why did he leave Sherry’s?

The

Providence Daily Journal (RI), November 8, 1901, claimed that Ranji left Sherry’s because needed to return to India as his mother was ill. Although his mother recuperated, his father then died. Ranji stated, “…

I became the head of the family and received some money.” The

Brantford Daily Expositor (Ontario, Canada), November 8, 1901, also stated that Ranji had inherited money upon the death of his merchant father. The

Boston Globe (MA), November 8, 1901, added a comment from Ranji, “

I am a native of India, where my father amassed a large fortune as a merchant. He has recently died and left me the bulk of his wealth. I went to India to take possession of this fortune and came back to America.”

These statements would later contradict Randi's claims that his father had been an Ameer, and that upon his father's death, his older brother assumed the throne. Later, Ranji claimed that he was the fifth son of his father, and thus wouldn't have become the head of the family. As his royalty claims have always been suspect, it seems more likely that his father was a merchant.

It was also around this time that there were mentions that Ranji was married. The Boston Globe (MA), November 8, 1901, reported that his wife was an English woman whom he married when he lived in London. The Evening Star (D.C.), November 8, 1901, added that when Ranji returned to India, he left his wife behind at their residence at 161 East 95th Street in Harlem.

After leaving for India in May 1900, Ranji didn’t return to the U.S. until about November 1901, roughly eighteen months later. He didn’t come alone, and first visited London and Montreal before returning to New York City. Ranji was accompanied by a “retinue” of about 28 people, all men except for one woman. While in London, some people believed that he was actually “Prince Ranjit of Baluchistan,” Indian royalty traveling with a retinue.

The

Philadelphia Inquirer (PA), November 10, 1901, reported that Ranji (pictured above) had arrived in London with his retinue, and occupied nearly an entire floor of a big hotel, and many assumed he was of royal blood. The article also claimed that Ranji was 24 years old. Previous speculation was that as Ranji now had a beard and mustache, and had been clean shaven during his previous time in London, many people didn't know he was the same person as the prior curry cook. Later, it also appeared that the people of Montreal seemed to believe he was royalty.

There was also a photo of Ranji's wife (pictured above), although her first name was not provided.

The

St. Louis Globe-Democrat (MO), November 7, 1901, reported that Ranji came to New York City, from Montreal, with a retinue of 29, including

Bahar Bux, a "

dancing girl." The

Providence Daily Journal (RI), November 8, 1901, added that when Ranji arrived in Harlem, he went to his own residence with his wife, and the retinue went to Forty Second street to find their own lodgings (where they would eventually reside at two rooms at 503 Greenwich Street).

Ranji also denied that his traveling companions were a “retinue.” He stated they actually included a servant, his nephews and three brothers, and that Buhar Bux was actually his niece. “

They have come here to learn American ways.” If true, and if later accounts were true that those three brothers were older than Ranji, then did they seem to take an inferior position to Ranji? Why didn't they stay with Ranji, or stay at much better quarters than the rest of the "retinue?"

The article noted that Ranji was wearing a small silver box. “

Fastened to his right arm by a silk cord was a small silver box.” Ranji explained, “I

t was my father’s and my father’s father, and now it’s mine because I am the head of the family. It is the karon, and it is our custom to wear it so.” Again, this contradicts Ranji's later statements that his oldest brother had become the Ameer upon his father's death, and thus he would have been the head of the family, entitled to wear the karon.

The article finally mentioned that the

U.S. Immigration Bureau was investigating Ranji and his "retinue," to determine whether there was a violation of the

Alien Contract Labor Law. This law, also known as the

Foran Act, was established in 1885, and essentially prohibited any company or individual from bringing unskilled immigrants into the U.S. to work under contract. There were exceptions under the law, such as for servants and domestics. If it were believed that Ranji had brought a royal retinue with him, then there wouldn't have been a violation of the law. However, if Ranji intended these people to work for him at a new restaurant, then the law might have been violated.

The

San Francisco Examiner (CA), November 24, 1901, provided maybe the first recipes from Chef Ranji, in an article titled “

Thanksgiving Recipes by Sherry’s Indian Curry Expert.” The article though referred to him as "

Prince Jack Rinzi," of Harachi, Beloochistan. He was said be be an expert curry cook, and who also prepared a number of other East Indian dishes. The article stated, “

He was a feature of Sherry’s. He was an artist chef and a chef artist.” It was then noted that he might open an East Indian restaurant and cooking school on Fifth Ave next month, once he has finished his “

Omar Khayyam” cook book (which he apparently never finished).

The article then provided some recipes from Ranji's book in progress, including:

Stewed Bananas,

East India Coffee,

Favorite Indian Entrée (like meatballs),

Indian Green Salad, and

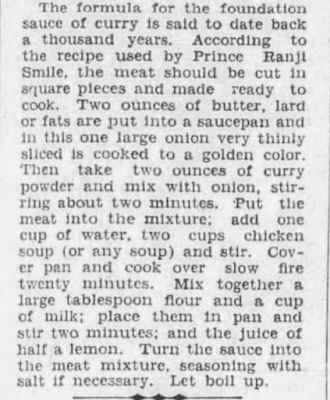

Favorite Indian Dessert or Kandahr. There was also a recipe for

Real Indian Curry (pictured above), which required Ranji's "

special curry powder."

It appears that Ranji opened his own East-Indian restaurant, the

Omar Khayyam (located at 325 Fifth Avenue, between Thirty-second and Thirty-third streets) in December 1901, which would close approximately six months later, in June 1902. This would be the first Indian restaurant in the U.S., although Sherry's, which concentrated on French cuisine, had previously served a few Indian dishes, prepared by Ranji. It wasn't too long before Ranji encountered some legal difficulties with his restaurant and workers.

The Leavenworth Times (KS), February 5, 1902, reported that Ranji had appeared before the supreme court on a complaint from Bahar Bux, who had alleged that she had been held as a prisoner at his restaurant. Seven other Indians joined the suit, claiming “they were inveigled to the United State under false pretenses by Ranji and are now penniless.” In front of the judge, Bahar denied her prior claim and stated she wished to continue working for Ranji, so her matter was discharged.

The other seven men alleged that they had first met Ranji in Bombay, and had been misled as Ranji had claimed he was an actual Prince. He told them that his plans were to travel to Genoa, Paris, London, Montreal, and finally New York City, and that those seven men would be his retinue. When they arrived in New York, Ranji them he wasn't actually royalty and that they would work at his new restaurant. In the end, the judge discharged their claims as well.

It was interesting to note that the article mentioned that Ranji’s business card read “Jo Ranji Smile, Indian Chef and Artist, Purveyor of All High-Class Indian Condiments; Major Domo of Sherry’s Restaurant, New York; late of Kaidonhi Lindh, London and Liverpool.”

The legal problems weren't over yet. The New York Tribune (NY), March 13, 1902, reported that the government had initiated a civil action against Roland R. Conklin, Stanley Conklin, and “Joe” Rangi Smile, for 35 violations of the Alien Contract Labor Law. The government sought to recover $1000 for each of those violations. All 35 of these Indians claimed they had worked at Ranji's restaurant but had received no wages.

Who were the Conklin's? The eldest Conklin, had lived in the building where Sherry's restaurant was located and met Ranji when he was cooking there. At some point, Ranji asked the Conklin's for $5000 to start his restaurant, and they gave him the money. They paid the rent for the first-quarter, and were listed on the lease, and then gave Ranji cash to journey to India, and obtain ornaments, furniture and more. As the Conklin's were seen as his backers, they were included in this suit. The hearing was then continued.

During these legal troubles, a fascinating article, titled Food and its Effect on Personal Beauty, appeared in Collier’s Weekly, May 10, 1902. The author was stated to be Ranji Smile, and it would include a number of recipes. The article was probably ghost written, as it was said Ranji couldn't write English.

The article began, “Physical Beauty, like good health, is all a matter of what one eats. Tell me what food a nation consumes most of and I will tell you the characteristics of its accepted type of loveliness.” It continued, “The national dish, I might say, always modifies the beauty as well as the health of the race which eats it. You cannot look for fair, shell-tinted complexions among a race of people who eschew the meat diet, nor can you hope to find soft, languorous eyes among a race of people who do not use hot seasonings in their food.” In addition, it was stated, “It is an undisputed fact among the best medical authorities that the ideal menu, from the standpoint of good digestion, comprises a liberal variety of diet. The same can be said of the ideal menu from the standpoint of personal beauty.”

Ranji also noted, “There is only too much of a tendency to restrict our diet to a few favorite dishes. That is a great mistake. We should all try to be cosmopolitan livers. We should try to cultivate taste for all wholesome dishes, and avoid, as much as possible, getting into what Americans term a “rut,” because culinary ruts are quite as detrimental to the digestion, as well as to beauty, as mental ruts are to the mind.” It was also mentioned, “It is sometimes objected that it is impossible, or at least impracticable, to elaborate the home menu without serious inconvenience in the kitchen, Especially is this cry raised in families where there is only one servant. This is not true, however. The average American of moderate means can have quite as much variety on his table as the millionaire. He can be quite as much of a culinary cosmopolitan as if he dined every day in a fashionable restaurant.”

The article then discussed Indian cuisine specifically. “The cookery of India especially recommends itself for the experiment of the American family. It is on the whole extremely simple, wholesome and nutritious, and in its inevitable use of sharp, hot seasonings adds an element wholly lacking in the food put upon the average home table, an element conducive alike to good digestion and to the development of those subtle physical qualities which come under the category of charm and beauty." Then, a series of Indian recipes were provided, although it seems clear that some of these recipes were the creation of Ranji, especially those dishes named after him.

“Kalook Ranji:—Select five fresh oysters—Blue Points preferably--half shell them, and sprinkle with black pepper and very fine pulverized salt. Pour a little tap sauce on the top of each oyster, and grate a liberal quantity of good cheese over this—any preferred variety of cheese will do--and put into a very hot oven for just two and one-half minutes by the watch."

“Kalook Omar Khayyam.—Put a piece of butter about the size of a walnut into a chafing-dish, melt the butter over a gentle flame, and squeeze into it the half of a good-sized lemon. Take a dozen nice large oysters and drop them one by one into this mixture, adding a teaspoonful of sharp chutney sauce, Stir gently until oysters are thoroughly hot and cooked through and serve in shells."

“Mulligatawny Omar Khayyam.—The bones of one large chicken from which the meat has been removed should be chopped into pieces about two inches long. Take a sprig of parsley, two sticks of celery and four onions, the latter sliced very thin. Put a large tablespoonful of butter into the saucepan, and when the butter melts put in the sliced onions and stir around with a silver spoon until the mass becomes a rich brown color. Add a dessert spoonful of best Madras curry powder, stirring vigorously all the while. Throw in the broken chicken bones, the celery and the parsley and add three and one-half cups of boiling water. Cook for two hours over a slow fire. Take out of sauce pan and strain through a finely woven muslin cloth. Return to cooking vessel, and add two teaspoonfuls of freshly boiled rice. Skim any fat that may come to the top and serve in bowls. This recipe, if followed closely, will result in a most delicious thin Mulligatawny."

"Fish Chowder.—Take an ordinary sized fish of almost any seasonable kind, boil until tender, and chop up bones and meat together into the consistency of ordinary hash, Add half a teaspoonful of curry powder, two tablespoonfuls of tap sauce, two tablespoonfuls of raw rice, two tomatoes sliced thin, one onion, half a cup of thick cream and two cups of water. Cook for half an hour over a slow fire, stirring gently from time to time. When done, run through a colander, season with pepper and salt, and return to fire until very hot before serving."

"Murghi Sindh.—Remove the skin and bones from a nice boiled fish. Chop up the meat very fine, together with a little parsley. Add a teaspoonful of Ranji chutney and mix the entire composition well with pepper and salt. Mold into croquettes, and dip each croquette into the beaten yolk of an egg, then dip into bread-crumbs, and fry in butter until brown. Serve with any desired sauce."

"Kafto.—Take cold chicken, lamb, mutton or beef as a basis for this dish. Remove skin, gristle and bones, and chop up exceedingly fine. Add a tiny piece of garlic, a small bit of fresh ginger, one green pepper sliced thin; mix well, and then add pepper and salt and a teaspoonful of tap sauce, Mold into patty-cakes and let them remain in hot oven until brown."

"Indian Murghi (Roast Chicken)—After one has eaten chicken roasted in Indian style one rarely wishes to eat it any other way. The chicken selected must be plump and tender, but not fat enough to be greasy. Take half a loaf of dry bread and soak it in rich fresh milk. Have ready prepared a little chopped up parsley and one Chile pepper and one onion, also chopped very fine. Mix, and add a scant teaspoonful of English mustard and a pinch of fresh ginger. Mix thoroughly and put into the milk-soaked bread. Fill the chicken with the stuffing and place in a pan into which, has been dropped a bit of butter the size of a walnut. Bake in hot oven until cooked through."

"Bombay Salads.—Peel and slice half a dozen oranges, take the inner leaves, the hearts, of half a dozen lettuces, wash well and drip. Place in bowl and sprinkle pepper and salt, placing orange slices on top. Mix a little olive oil with good white vinegar and pour over salad and serve from bowl."

"Omar Khayyam Salad.—Lettuce, watercress, tomatoes and celery are the ingredients of this delicious salad. Wash all thoroughly and put in icebox for some time before preparing. Skin the tomatoes, and chop up the celery and watercress. Take the yolk of a hard-boiled egg, a little milk, a teaspoonful of chutney, mix well and add pepper and salt, Then beat until perfectly smooth and pour over salad."

"Souf.—Peel six juicy apples and slice thin. Take the juice of six oranges, a cup of thick cream, a handful of almonds chopped fine, a half-dozen pistaches, mix well and flavor with grated nutmeg; pour over sliced apples and put in hot oven for ten minutes or until such time as the apples are cooked through. Serve hot with cream."

"Khurbooja Smile.—Take one of all the different fresh fruits obtainable—oranges, apples, bananas, cherries, berries or whatnot —wash, peel, slice or cut as may be respectively necessary, into pieces about one and one-half inches square. Slice any kind of rich cake and soak in rich milk. When thoroughly soaked, beat into a batter and stir in the chopped fruit. Flavor with a little grated nutmeg and two or three chopped almonds. Bake in hot oven, and when done put in icebox until ready to serve."

"Chavel (Cold).—Prepare rice same as in direction for hot chavel. Put on ice, and when cold serve with strawberry, vanilla and pistache ice cream heaped together on the dish."

Ranji then added, "Certain districts of India are famous for the peculiar excellence and delicate flavor of their coffee. The Indian chef probably prepares coffee in more different fashions than any other, and of these many recipes I select the following as possibly capable of the best results in the American kitchen:"

"Indian Rose Water Coffee.—Only the purest straight Mocha should be used in the preparation of this aromatic beverage. The coffee berries must have been carefully roasted, but not too well done, and should be ground very fine. A silver coffee-pot should be used; no tin or granite ought ever to be used in making coffee. Put four cupfuls of freshly boiled water into the pot and add eight heaping teaspoonfuls of coffee. Stir until the coffee boils up, and before, removing from the fire throw in three teaspoonfuls of pure rose water. Serve in small cups with sugar, but no cream."

Randi's legal woes worsened. The New York Tribune (NY), May 21, 1902, reported that Ranji and 18 members of his "retinue" had been taken to Ellis Island, and another dozen men were being collected. Ranji was being called to explain why he felt he hadn't violated the Alien Contract Labor law. It was also stated that Ranji had not been seen at the restaurant for several months, and “…it is said that owing to a lack of patronage many of the waiters were likely to become public charges.” Of the 37 men that came to New York with Ranji, several had already returned to India.

The Philadelphia Times (PA), May 23, 1902, then reported that Ranji and 31 of his men were still on Ellis Island and were probably to be deported.

The Sun (NY), July 1, 1902, provided a brief synopsis of the arc of the Omar Khayyam restaurant. Initially, when the restaurant opened, the walls were hung with Indian draperies and dim lights from hanging lanterns. There were white robed waiters, in voluminous turbans, and live Indian music played in the background. “Everything that could make the restaurant a success was done, but the public, after the first few weeks, showed no inclination to patronize the place.”

It also noted, “The restaurant struggled through the winter, with Ranji hoping for its success, but the spring brought no better luck.” The Lincoln Journal Star (NE), July 21, 1902, added “The opening night was celebrated by a banquet, which was attended by many New York millionaires and their families, and the place became the talk of the town.”

Why did the restaurant fail, and so quickly? No explanation seems to have been provided. Although curry had been popular throughout the 19th century, maybe it was seen as more an occasional treat, and not something for common consumption. Maybe the public was not ready for a full Indian menu, except maybe for special occasions. This must have been very disappointing to Ranji, who would never open his own restaurant again. Instead, he would travel from location to location, cooking for weeks or months, before moving on to another place.

The Lincoln Journal Star (NE), July 21, 1902, noted that Ranji had been found liable by the courts, and owed $1000 to each of 14 former employees for violations of the Alien Contract Labor Law. Why only 14 violations, when there had been over 30 initial charges? No explanation was provided. those 14 former employees later claimed that Ranji had transferred the restaurant to different owners, and somehow evaded payments of these fines. And as these employees were also deported, back to London, they had little recourse.

Was Ranji actually deported? It doesn't appear so, although if he had been, he was able to return to the U.S. in less than six months. He would then begin traveling across the U.S., cooking at many different locations.

The

New York American & Journal (NY), November 30, 1902, noted that Prince Ranji Smile, and a suite of East Indian attendants, would conduct cooking demonstrations in the Lectura Hall of

Simpson Crawford Co., a retail store. Where did these attendants come from? Did Ranji bring them from Indian, or were they already in the U.S.?

Good Eating, January 1903, a magazine published by Simpson Crawford Co., provided a list of their grocery prices. Not only was Ranji doing cooking demos for them, he also allowed them to sell packets of his curry powder. Under “Sauces and Relishes”, the store sold two brands of Curry Powder, including one from Cross & Blackwell’s, which sold 2 ounces for 12 cents, a bottle for $1.40, and 4 ounces for 18 cents. The other brand was by Prince Ranji Smile, which sold a small package for 25 cents (equivalent to about $9.00 in 2025), a medium for 55 cents, and a large for $1.25 (equivalent to about $45.00 in 2025).

The Masonic Standard, March 7, 1903, mentioned that E. Sir James T. Clyde, of the Palestine Commandery, with an elegant restaurant at Broadway and Seventy-fifth Street, had hired Ranji to prepare Indian dinners.

In 1904, Ranji petitioned for U.S. citizenship, but apparently it was denied, probably due to the color of his skin. It's also around 1904 that Ranji started to once again claim that he was actual royalty, and embellish his history. Could the two issues be related? It's possible that Ranji created this royal persona to avoid potential deportation, as well as a way to avoid some discrimination. By creating this larger-than-life persona, and becoming a bigger celebrity, he gained much more support and became a much-valued chef all across the country.

The Philadelphia Inquirer (PA), October 13, 1904, mentioned that Ranji's father had once reigned in Karochi, India. While Ranji had previously worked at the Hotel Cecil in London, he now claimed that Albert, the Prince of Wales (who was currently the King) had attended the opening dinner. At that dinner, Ranji had prepared a special cocktail, the Omar Khayyam: a blend of Indian wine, rosewater, crème de menthe and a “brand of spirits that is preserved as a secret by the royal families of India.” The Prince was quite taken with it all and allegedly had his jewelers create a set of gold buttons, marked with the royal crest, as a gift to Ranji, who still wears them. Three buttons are worn on each sleeve, and five buttons on the front of the coat.

Ranji claimed to be the “King of the Chafing Dish,” the “sole inventor of the Omar Khayam cocktail,” and the “originator of Kalloh-raji.” Recently, Ranji was hired by G. Jason Waters, of Philadelphia, who wanted something new for his city. The dining hall of the Flanders was closed for the summer and then reopened with Ranji, accompanied by 7 other East Indians, which included a band and a “real live East Indian fakir, who will entertain the guests by making rose bushes grow from the plates in front of them and perform the world celebrated rope trick.” It was also mentioned that “All cooking is done by the Prince directly in front of the person to be served.”

A chafing dish is a metal cooking or serving pan on a stand with an alcohol burner beneath it. It can be used as a warming tray, or for table-side cooking, also known as gueridon service. This table-side service was often conducted at high end restaurants, and apparently Ranji often engaged in this type of service. This appears to be the first time though that a newspaper quoted Ranji claiming to be the “King of the Chafing Dish.”

The Press of Atlantic City (NJ), October 31, 1904, noted that “A real nobleman, a Prince in rank, will, in all probability, preside over the kitchen of the Hotel Windsor next season.” It continued, "He’s employed by G. Jason Waters, owner of the hotel and the Flanders, where Prince is currently working.

The Scranton Truth (PA), July 9, 1905, mentioned, “Prince Ranji Smile, whose eldest brother is the present reigning Ameer of Baluchistan, is in Chicago. He is making a tour of the world.”

Meeting an actual king! The Inter Ocean (IL), June 14, 1906, stated that Ranji was now working at the Auditorium Annex in Chicago. The Maharajah Gaekwar, King of Baroda in India, came to Chicago and dined at the Annex. It was then reported that when Ranji tried to greet the King, he was ignored, and the King later said, “He is a cook."

However, the

St. Joseph News-Press (MO), June 15, 1906, presented a drastically different view, stating, “

There was a joyful meeting between the maharajah and Prince Ranji Smile,..." They conferred on lunch and came up with menu pictured above. The

Evening Nonpareil (Iowa), August 4, 1906, later added, "

Yesterday, the Gaekwar of Bovoda, India, declared Prince to be a “real prince.” He also said, Ranji is the “

fifth son of my old friend, the ameer of Beloochestan—one of our important provinces.” Did Ranji somehow persuade the Gaekwar to play along with his ruse, and claim that Ranji was truly of royal blood?

A new location. The

Atlantic City Gazette-Review (NJ), July 2, 1907, reported that Ranji, formerly of the Auditorium Annex, was now working at the

Windsor Café.

Two months later, the Times Herald (D.C.), September 14, 1907, noted that Ranji, the 5th son of the late Ameer of Baluchistan, was now in Washington, D.C., a guest at the Riggs House. Allegedly, a year ago, Ranji married an American girl in Chicago, the former Rose Schlueter of Philadelphia. She was said to be not quite 21 years old and “a striking type of the American beauty.” About a year ago, Ranji visited London and met some Americans who were friends with Rose. When he returned to Chicago, he found her there and they married within 3 months.

As to his former wife, she allegedly died, but there seems to be lacking evidence of such, and the fact her first name wasn't provided by the press, it's difficult to track her down. There also appears to be a lack of evidence that Ranji actually married Rose. Ranji would eventually have a track record of allegedly marrying women, but many of those marriages never occurred.

The Times Herald also stated that Ranji had been offering cooking demos in different cities and “These are made in a set of silver chafing dishes,..” He allegedly had a retinue of 23 servants, which included a juggler and dancing girl. Ranji planned to remain in the city for an indefinite stay, having just come from the Windsor, an exclusive hotel patronized by millionaires from New York.

His time in Washington, D.C. was apparently short as he next appeared in Indiana. The Indianapolis News (IN), October 19, 1907, stated Ranji would work at the café of a local hotel for several days, “announcing an intention to give demonstrations of his superiority over all other kings of the chafing dish and rough-riders of the gas range.”

Next stop, St. Louis! The St. Louis Post-Dispatch (MO), December 2, 1907, reported that Ranji, who was 28 years old and the fifth son of the late Ameer of Beluchistan, had come to St. Louis and would hold a cooking demo at a local hotel. Ranji stated, “The seat of character is in the kitchen...Laxity in morals springs from the beefsteak and virtue has its root in a light diet of fruit, eggs, and chickens,…” He continued, “You Americans hustle too much...You eat too much beefsteak. Beefsteak makes a man wild, like a beast.” And then he said, “In India we don’t eat beefsteak and we think 102 or 105 is a nice ripe age to say good-bye.”

Ranji then noted, “I shall teach the people of St. Louis how to live long and be honest and not fierce.” He then boasted, “I am a genius at the cooking,..” He also discussed his culinary beginnings, “When I was a baby I used to cry. They wouldn’t know what I was crying for. Then they would give me something to mix and cook, and I would be happy and keep quiet.”

Continuing, Ranji addressed the topic of compensation. “

It is not a question of money. I have a royal revenue from Beluchistan, but I like to get away from there. I hate the royal etiquette. Here I am free. I go. I come. It is nobody’s business. At home it is different. Everything must be just so.” Plus, “

He makes no charge for communicating his secrets—how to make curries, how to mix wonderful drinks.”

The

St. Louis Post-Dispatch (MO), December 15, 1907, provided a little more information about the new wife of Ranji,

Rose Schlueter, including her photo above. The article stated that in February 1908, she would travel to India and be presented at the royal court of the Ameer of Baluchistan. Only royalty would be invited to this special event. There was a lengthy description of the preparation and ceremony that would occur. It was also noted that Baluchistan was one of the largest provinces in East India, being 550 miles wide and 450 miles long, and that there were about 1.5 Million people under the direct power of the Ameer.

The article then noted, “Prince Ranji Smile is the third brother of the ruling Ameer, and the youngest one in the royal family, and the special pet. He was educated in India, being taught English, and then sent by his brothers abroad. His mission was a double one—he was to broaden his education and to act as a diplomat for his country.” Most other articles claimed that Ranji was the fourth brother of the ruling Ameer, and no other article claimed that he had been sent anyway as a diplomat.

The article continued, “He first went to London and there met Miss Rose Schlueter, who was traveling and studying in England. That was six years ago. He became such an ardent admirer that he joined her party and traveled over Europe. After she returned to the United States he soon gave up his diplomatic duties and followed her. He went to her Chicago home, and found her father to be a rich banker and broker.” Then, a few months ago, they were married. This information conflicts with the earlier report that he first met Rose last year in London.

Finally, the article added, “Prince Smile has a hobby, and that is for pretty women and longevity. He attributes long life to careful eating.” It also noted, “He is a famous cook, and has many different kinds of chafing dishes, knows more about royal cooking than almost anyone, and has invented many new dishes.”

The

St. Louis Post-Dispatch (MO), January 28, 1908, apparently corrected their prior error and now noted that Ranji was the 4th brother of the Ameer. Ranji was now working as a major domo at the

Hotel Jefferson, where he had another problem with an employee and wages. Ranjo had hired

Sahi N. Buchakji, a 20 year old "

Hindoo" fakir, who had sued Ranji for due wages. Ranji told the police that Sahihad had stolen from him, 3 trunks of costly Eastern wares and stuffs which were worth about $20,0000. Sahi was arrested, but when the police learned of the quarrel between the two men, he was released.

The

St. Louis Post-Dispatch (MO), February 9, 1908, noting that Ranji was “

the Indian culinary curry artist,” presented his recipe for

Curried Chicken. The recipe isn't fully useful as it asks you to use "

the proper proportion of curry powder," but fails to note that proportion.

Seven months later, Ranji headed to Virginia. The

Ledger-Star (VA), September 9, 1908, stated that Ranji had visited the

Hotel Fairfax, in

Norfolk, having coming from Atlantic City, New Jersey. He came to Norfolk with 7 attendants and 22 trunks, stating his stay would be indefinite and didn't give a reason for the visit. The

Virginian-Pilot (VA), September 10, 1908, then added that Ranji would give a cooking demo, and was awaiting 58 attendants, who should arrive in a day.

A no show! The

Virginian-Pilot (VA), September 11, 1908, reported that Ranji's 57 attendants had failed to arrive. Nonetheless, Ranji was going to take charge of the new tea room at the Fairfax. The

Virginian-Pilot (VA), September 13, 1908, then reported that the new

Oriental Tea Room at the Fairfax had opened last night, and about 1000 people attended, which was obviously a great showing.

The

Virginian-Pilot (VA), September 16, 1908, printed the above ad for their new Oriental Tea Room, noting Ranji was "

The King of the Chafing Dish."

Ranji's time at the Fairfax would only last a couple weeks, before he moved on to a new location. The

Washington Post (D.C.), September 18, 1908, printed the above ad, noting that Ranji, the "

King of Curry Cooks" would appear at

Harvey’s restaurant, on October 1, for a few weeks.

Ranji's time at Harvey's was also short. The

Plain Dealer (OH), October 9, 1908, had an ad indicating Ranji was now working at the

Hotel Lincoln in

Pittsburg, Pennsylvania.

As for his time at the Hotel Fairfax, the

Virginian Pilot (VA), October 18, 1908, indicated that Ranji had "

silently departed" from the town, which might indicate he didn't mention to the Hotel that he had another job at Harvey's. The article also stated, “

But Ranji was a good cook. He fixed dishes fit for a king and the hundreds who partook of them at the Fairfax said they were the best ever. And there were some connisseurs among the patrons.”

More traveling. The

Portsmouth Star (VA), November 11, 1908, noted that Ranji was staying at the

Park Hotel in

Richmond, Virginia, having come from Norfolk a week or so ago, seeking work.

A week later, the

Baltimore Sun (MD), November 18, 1908, indicated that Ranji was staying at the

Hotel Kernan, in Baltimore, and was cooking his own meals. The next day, the

Baltimore Sun (MD), November 19, 1908, it was said, “

The Smile family rules Beluchistan. His father was ruler of the province until his death 25 years, and Ranji’s oldest brother succeeded to the place.” Ranji also claimed that he had come to the U.S. in 1901, and blamed the customs men for nearly putting him out of business, which would have been when they deported his employees.

Earlier newspaper accounts claimed that Ranji had returned to Indian in 1901 and his father had died. That was only 7 years ago, and not the 25 years he now claimed. It was his father's death in 1901 which had allegedly garnered Ranji's wealth as his inheritance. In addition, as Ranji was likely born around 1879, and if his father had died 25 years ago, Ranji would have only been about 4 years old when his father died. That would contradict a number of previous statements Ranji made about his time with his father.

The article continued, noting Ranji returned to the U.S. in 1902 and has since has been traveling throughout the country. It was also said that Ranji married his current wife in Chicago in 1906, and that she was on her way to Baltimore from India, where she had been visiting her brother-in-law,

Borokan, the ruler of Baluchistan.

The

Hotel Monthly, December 1908, provided a menu for an special Indian dinner event, presided over by Ranji, and held at the

Hotel Lincoln in

Pennsylvania.

The Columbus Sunday Dispatch (OH), December 6, 1908, mentioned that Ranji's wife had been in India, and “she liked so well that she would have remained” except that Ranji threatened to find another wife so she hurried back to the U.S.

Another new city. The Buffalo News (NY), December 31, 1908, reported that Ranji had registered at the Hotel Statler and was seeking a new job. It was also briefly noted that his father had died 23 years ago. That contradicts numerous prior accounts.

The Buffalo Evening News (NY), January 2, 1909, later added that Ranji was still at the Hotel Statler. In addition, it was alleged that Ranji had been knighted by the Prince of Wales back in 1893, when Ranji would have been only 14 years old. Ranji claimed the Prince had enjoyed his cuisine, and knighted him as a reward, as well as giving him a number of gold buttons with the royal seal. However, at the time, only the King technically could knight someone, so the Prince couldn't have done so.

The Democrat & Chronicle (NY), January 14, 1909, noted that Ranji, starting on January 14 and for a limited time, would give a culinary demo at the Powers Hotel in Rochester.

The New York Times (NY), July 31, 1909: indicated that Ranji was now working at the Modern Island Hotel at Oscawana-on-Hudson. He would work here at least through September, although possibly longer.

After a gap of almost a year in newspaper coverage, the Alexandria Gazette (VA), March 15, 1910, briefly noted that the Prince’s wife was currently in Philadelphia with her family. However, two months later, the New York Evening Journal (NY), May 20, 1910, reported that Ranji was going to marry Anna Maria Washington Davies, of West One Hundred and Fourth Street of Newport Court. However, that was also one of Ranji's former addresses. What happened to his previous wife?

In addition, it was mentioned that Ranji was cooking at a hotel on Oscawanna Island. So, it's possible that Ranji had been working there for almost a year.

The Baltimore Sun (MD), May 20, 1910, reported that Ranji had acquired a wedding license to marry Anna Maria Washington Davies, age 24, who was born in Wales. They were supposed to wed on May 24. It was also noted that Ranji's father was named Haji and his mother was Princess Zora. Subsequent newspapers though didn't confirm that the wedding ever took place, and soon enough, Ranji had moved on to marry someone else.

The

Times Union (NY), August 6, 1912, reported that Ranji had married

Violet Ethel Rochlitz, age 20, of 41 East Twenty-second St. She was the daughter of

Julian W. Rochlitz. At this time, Ranji claimed to be 30 years old. The two planned to move to Delhi, Indian, and open a hotel, like an American one, for American tourists. That would never actually happen.

The

Evening World (NY), August 6, 1912, provided the above photo of Ranji's new bride. The article also stated that the Prince had gotten married a year ago, to Anna, which would have been 1911, but that she had died. The prior articles had indicated Ranji's plans to get wed in 1910, but the marriage license was never returned, as was required by clergymen. So, the marriage might not have actually taken place. On his new marriage license, Ranji noted once again that he was 30 years old, the same as he had two years ago. This helped to cloud his true age. Ranji's was also noted to be residing at the

Café Beaux Arts on East Fortieth Street.

More about his prior "wedding." The Sun (NY), August 7, 1912, reported that previously, on May 19, 1910, Ranji had secured a wedding license with Anna Maria Washington Davies. A few months later, Ranji sent out a circular stating “My wise and adored Princess wanting a home, I found this beautiful, enchanting island.” That referred to Oscawanna Island, where Ranji worked for a time. Then, the article reported that yesterday, Ranji claimed that Anna had been dead for nearly two years. In addition, Ranji Prince now said his mother was Princess Zora Kahlekt, although two years ago, her name was given as Princess Zora Narbeboxy.

Royalty or not? The

New York Times (NY), August 7, 1912, reported, “

No records have ever been found proving that “Joe” Smile is a real Prince.” This was one of the only newspapers at this time which came forward to contest that Ranji was royalty. Most of the other newspapers seemed to accept his claim as true.

The

New York American (NY), October 6, 1912, and

Brooklyn Eagle (NY), November 3, 1912, mentioned that Ranji was working for the

Simpson Crawford Co., where he previously worked back in 1902.

The

Brooklyn Daily Times (NY), November 9, 1912, printed an ad for the Grand Opening of

Raub's new Oriental Dining Rooms. Prince Ranji, the King of the Chafing Dish, would cook at the new dining rooms, with "

Hindoo Girls as Waitresses" and "

Hindoo Boys as Attendants," all garbed in Oriental Costume.

Ranji arrived in Massachusetts! The

Springfield Daily Republican (MA), March 23, 1913, posted an advertisement that Ranji would be cooking at the

Hotel Kimball in

Springfield, serving East Indian dishes at noon, the tea hour and dinner. The ad also claimed that Ranji was royalty, the son of the late Ameer of Balouchistan. The

Springfield Evening Union (MA), March 27, 1913, added, “

That Prince Ranji Smile will be retained in the Hotel Kimball for some time to come is evidence from the instant popularity of his dishes. Despite the inclement weather, the crowds in the dining and grill rooms kept the prince busy at every meal yesterday…”;

The Springfield Daily Republican (MA), April 6, 1913, provided another ad for Ranji and the Kimball.

The Springfield Daily Republican (MA), April 9, 1913, noted that Ranji's wife, the former Violet Hochlitz, had come to town from New York. It was claimed that they met at an East Indian dinner party held on Oscawana Island, and then they were married in New York on August 6, 1912. In the future, Ranji and her are planning to travel to Delhi to open a large hotel. She will also then renounce her Christian tradition and be married “under Mohammedan law.” It then appeared his time in Springfield may have ended in the first week of May.

The Evening Sun (MD), May 1, 1913, added some information about Ranji's wife, claiming that “her husband permits her to eat only dishes he choose and prepares for her.” Ranji “ascribes her rare beauty to his case of her food.” The article then alleged they had eloped in New York, and then traveled to India, where his wife became a Muslim. This contradicts the previous article that she hadn't yet become a Muslim.

Ranji working in Boston! The Boston Post (MA), May 1, 1913, noted that Ranji and his wife were now in Boston, and in two days, he would offer cooking demos, especially to women, at the Copley-Plaza. The article also claimed that Ranji was of royal blood, which would soon be disputed!

The Boston Post (MA), May 2, 1913, published an article titled, "Calls Prince of India Imposter." Editor and Lecturer Rustom Rustomjee declared that at his lecture next Monday, he would declare Ranji to be an imposter, and not of royal blood. Rustom and his wife have been in Boston for two years, and he had previously been in the newspaper industry in Bombay, India. In response, Ranji stated he should hire an attorney and that Rustom should be arrested for slander.

Rustom stated, "He may be a prince of cooks, but he is not a prince of the Indian aristocracy." In response, Ranji said, "Mr. Rustomjee is a low caste fire worshipper and a parsee, and he is jealous of me because I am a Mahometan." Rustom also claimed he had known Ranji when he first came to New York to cook at Sherry's, but Ranji initially denied ever knowing him. However, Ranji changed his statement, and claimed he did know Rustom and said, "He was not an editor, not even an East Indian. Rustomjee is from Persia, a low caste fire worshipper, who came to this country to be a fortune teller, a palm reader down in New York and Coney Island."

However, information about Rustom's Monday lecture does not seem to indicate he followed through on exposing Ranji. Instead, the lecture warned against East Indian swamis, seers and prophets in some of the major cities of the U.S.

The Boston Journal (MA), May 10, 1913, noted that Ranji was now cooking at the Copley-Plaza Hotel, and one of his guests was Charles M. Schwab, the steel king. He enjoyed Ranji's cuisine so much, he tried to hire him away from the hotel but Ranji refused his offer.

The Boston Journal (MA), May 13, 1913, reported that Ranji would host the Aub Che-Mahabani luncheon at the Copley-Plaza. The article also stated that Ranji's most famous menus were composed of the most part by rice and curries, and that Ranji claimed he possessed over 500 recipes of curries and rice dishes.

The

Boston Globe, June 8, 1913, printed ad ad for

Henry Siegel Co., located at Washington and Essex Streets, Boston. Ranji was booked for a two-week stay, serving his curried dishes in their 5th floor restaurant.

Six months later. The

Boston Evening Transcript, December 6, 1913, noted that Ranji would be again serving his curried dishes at Henry Siegel Co. It's unclear whether Ranji had been continually working at Henry Siegel for the past six months or not.

The

Pawtucket Times (RI), April 22, 1914, provided an for the

Dreyfus French Café-Restaurant, where Ranji would be cooking.

The Washington Post (D.C.), July 24, 1914, stated that "Miss Violet Rochlitz," who had been and might still be the wife of Ranji, was now on the chorus line of "The Passing Show of 1914." Her father, Julian, had been a photographer and Violet sometimes worked at his studio. Violet was initially educated in a convent school and then later a Quaker academy. Other newspapers also referred to Violet as "Miss." Had she divorced Ranji by this time? Or was she using "Miss" as a stage name?

The

Newark Evening Star (NJ), September 24, 1914, indicated that

Violet Rochlitz was going to be part of the chorus of a theater company performing in

Dancing Around, beginning on October 5. The

Springfield Daily News (MA), October 22, 1914, stated that

Dancing Around was a "

musical spectacle," as well as a "

pretentious and mammoth production which embraces a little of everything,..." The featured performer was

Al Jolson.

The

New York Hotel Record, October 27, 1914, noted that Ranji was now working at the

Hotel Imperial. Ranji stated, “

We could live so much longer if we would take daily a little simple food. There is so much indigestion in America. Americans eat too fast and too much. We don’t find it so in India. People there are not dosing all the time. They are living simple lives and are destined to live longer than the westerners.” Ranji also stated, “

There is not a meal that should be without rice. It can be cooked in many ways.” And he added, “

Keep your youth by the proper food. Don’t resort to cosmetics for beauty.”

This article also presented two recipes, for curry of chicken and rice.

Continuing to contest Ranji's claims to be royalty, the

New York Times (NY), June 7, 1915, stated, “

Ranji Smile, a curry cook from India, who was called a Prince until it was discovered that he wasn’t one,…” The article reported that Ranji had been arrested for not paying his check, for $6.50, at an Italian restaurant for a meal of spaghetti and wine. Ranji told the judge, who knew him from his days at Sherry's, that as he sat in the restaurant, many people came over to see him and drank wine. When they all left, Ranji and a barber, were stuck with the check. The judge discharged the entire matter against Ranji.

The

Evening World (NY), June 18, 1915, presented an ad for the

Cosmopolitan Garden, the "

World’s largest pure food market." Ranji would be there, at the "

Hindoo Market booth,“ and the ad also had a coupon for a free $25 recipe, in Ranji's own writing, for curried chicken and rice. It was claimed that “

This famous recipe was sold to Lady Vectam DuLupsing of India for two hundred and fifty dollars.”

Over a year later, the

New York American (NY), September 17, 1916, mentioned that

Julius Keller would be

opening an East Indian palace with Ranji as cook at

Maxims. However, it might not have come to fruition as the

Buffalo Courier Express (NY), September 30, 1916, noted that Ranji would be appears at the

Cataract House Gardens in Niagara Falls.

The

Record (NJ), September 14, 1917, stated that Ranji would make an appearance for a time at the Robert Treat Hotel, during lunch, dinner and supper. He would remain there at least through October 25.

Back to Massachusetts. The

Worcester Evening Gazette (MA), February 11, 1918, reported that Ranji had been working at the Copley-Plaza but now had moved on, with a trio of Hindu girls, to work in the

Colonial room at the

Bancroft Hotel.

Back to New Jersey. The News (NJ), April 9, 1918, noted Ranji was once again working at the Robert Treat Hotel, during lunch, dinner and supper.

Wedding bells! The Brooklyn Daily Times (NY), April 11, 1918, reported that Ranji, age 36 of 250 East Sixty-First Street, Manhattan, had acquired a marriage license to wed Mae Walter, age 19, of 1069 Lafayette Avenue. The article stated, “A real Prince visited the Marriage License Bureau today.” It was also claimed, “This is his second marriage, and his bride’s first,” and they were to be married on April 13. The Brooklyn Eagle (NY), April 15, 1918, then reported he had been married the previous night. It was also noted that Ranji's business cards had " H.R.H.," standing for “His Royal Highness.”

Back to New Jersey. The News (NJ), May 31, 1918, noted Ranji was once again working at the Robert Treat Hotel, during lunch, dinner and supper.

Marital discord! The Brooklyn Eagle (NY), June 7, 1918, reported that Ranji, who was said to be 39 years old, claimed his proper wife, Violet Ethel Rochlitz, was dead. Sarah Lohman indicated that Violet Rochlitz died of an infection, which unfortunately spread to her heart, killing her.

Ranji's current wife had brought a complaint against him for disorderly conduct, and after that complaint, Ranji went to her parent's home, where he smashed a window. He was arrested and held on $200 bail. The Brooklyn Daily Times (NY), June 8, 1918, then reported that the case against Ranji was discharged. Ranji stated, “The girl only married me for my money. I know she’s a good girl and I’m willing to go back and live with her. It is her parents that caused all this trouble." His wife was now living with her parents.

Back to New Jersey. The News (NJ), October 1, 1918, noted Ranji was once again working at the Robert Treat Hotel, during lunch, dinner and supper. This was maybe his fourth time period working here.

Variety, January 10, 1919, published a lengthy article about “Prince Ranji Smile of India, Culinary Expert of the Chafing Dish; East India Dishes and Curry.” Ranji was now cooking at the Hotel Majestic, New York City. The article claimed, "The 'Smile' in the Prince’s title has been modernized from his native name, but Prince Ranji is the portion given him when born, by his royal father, a Rajah of India, and the wealthiest noble of Punjab, a province at the foothills of the Baluchistan mountains."

Ranji was then described as "picturesque in his costume of an East Indian. He is swarthy in coloring, with a mustache tightly rolled to either side, and his turban has just the least of a military tilt to it."As his his life story, the article alleged, "He left his home when a boy, wandering into the hills, becoming lost and finally picked up by bandits, who held him for a ransom approximating $100,000 in American money, when learning who he was. Hearing of the large forces sent by the Rajah to recover his son, the bandits turned the boy adrift and fled."

The article then continued, "Having carried the Prince by this time far into the mountains, the youngster led a wild life for several years, until at about 16 he was taken in by the colonel of an English regiment, sent to Burmah; but having forgotten his name and residence while the fears of the jungle were forced upon him in his wanderings, the Prince could furnish no information regarding himself. The English at Burmah developed a fondness for the boy and sent him to Calcutta. He eventually left there and traveled until 22, when reaching London."

The story then went on, "Here some folks interested themselves in him and through their efforts memory of his home was restored; illustrations of the scenes and the mention of his family name bringing back his early youth. Writing to his father, who had spent over $2,000,000 attempting to locate his lost son, the father replied, saying he believed the letter to have been written by an imposter. It embittered the Prince, who has never returned to India. Embarrassed in London by his family’s repudiation, the Prince came to America."

The article also stated, "The Prince is said to be the most proficient East Indian chef in Europe or America, but says the honor was thrust upon him by his guests." It also claimed that he had been married three times. Ranji "thinks a well-cooked curry is preferable to wealth." He also allegedly "came to New York with the idea of starting a dancing cabaret on Broadway, wholly built of glass and cupaloed."

The Chicago Defender (IL), March 6, 1920, mentioned that The Hindustan, which supplanted the Libya, would soon have an Indian garden and restaurant for the summer months, with Ranji as the proprietor.

The Intelligencer Journal (PA), October 23, 1920, noted Ranji was performing cooking demos at the Watt and Shand, a large store.

Six months later, the Cincinnati Enquirer (OH), April 30, 1922, said Ranji, who had come from the Hotel Breslin in New York, was now at the Hotel Sinton, and would prepare East Indian dishes at luncheon and dinner. The Cincinnati Enquirer (OH), June 6, 1922, mentioned that Ranji would be serving dishes such as chicken or crab meat Indian curry with Bengal chutney and spiced cocoanut.

The New York Hotel Review, September 2, 1922, mentioned that Ranji was once again a chef at the Breslin Hotel.

Ranji wouldn't be mentioned in the newspapers for about another four years. The Cincinnati Enquirer (OH), June 2, 1926, mentioned that Ranji was working once again at that Hotel Sinton, after Ranji had previously spent many months in Havana and Miami.

And the next mention was in the

New York Evening Journal (NY), July 12, 1926, under an article titled, "

Hindoo Mystic Puts Jinx On Giants' Rivals." It was claimed that the Giants met Ranji at the Sinton Hotel, and that Ranji was an old friend of

John McGraw, the manager of the Giants. Ranji told McGraw that he would bring the Giants luck. The article stated that Ranji is, "

...master of the Indian sign which he is employing on behalf of John McGraw's reawakened pennant chasers. Ranji put the Hindoo hoodoo on the Reds over in Cincinnati, and the world knows now what happened to the Reds." Ultimately, the Giants never made it to the World Series that year, so Ranji's power was obviously limited.

The

Evening Sun (MD), April 22, 1927, provided a recipe for Ranji's curry, which could be prepared with any type of meat.

References to Ranji then nearly dried up, and his ultimate fate is unknown. In Eight Flavors: The Untold Story of American Cuisine (2016), Sarah Lohman stated, "In 1929, just a few months before the stock market crashed, Smile boarded a steamship bound for England. He went alone—no wife or children by his side, despite his many relationships. When he arrived in Southampton, the ship’s manifest listed that his destination was the Hotel Cecil, his old employer. He might have returned to a job there, but the ship’s manifest also indicated he didn’t intend to make his home in the United Kingdom. I wonder if he was just passing through on his way back, finally, to Karachi. Either way, that’s the last known record of Smile; there are no further documents to indicate how he might have lived the rest of his life and how he might have died."

There was a final reference to him in the newspapers, the Brooklyn Eagle (NY), May 10, 1937, where Mae Smile filed for an annulment of her marriage to Ranji. Why did it take so long, nearly 20 years after her wedding, for her to file for an annulment? It's likely she didn't know where Ranji was now living, or whether he was even still alive or not.

Prince Ranji Smile obviously was an ardent promoter for Indian cuisine, exposing many Americans, across the country and over the course of nearly 30 years, to curries and other Indian dishes. His culinary skills were impressive, and no one ever seemed to have a criticism of his dishes. However, he told numerous lies and false stories about his background and personal history, sometimes claiming to be royalty. These tales, even though often untrue, helped to bring him additional fame and celebrity, atop that achieved through his amazing culinary skills. Maybe one day we will learn the ultimate fate of Ranji Smile.