--The New England Magazine, v.28 (March to August 1903), China in New England by Herbert Heywood

Take a leisurely walk through Boston's Chinatown, exploring Harrison Avenue, Beach Street, Tyler Street, Knapp Street, and more. You'll quickly note numerous restaurants, offering a variety of Asian cuisines, although Chinese restaurants, including a number of regional spots, predominate. So many delicious options, from Soup Dumplings to Dim Sum, Banh Mi to Ramen, with many restaurants offering excellent value as well.

However, what was the first restaurant to ever open in Chinatown? This question intrigued me so, back in 2019, I conducted an initial, limited online search to try to determine the answer.

Chinatown, as an established neighborhood, has been around for roughly 140 years, and most sources I found claimed that the first Chinese restaurant in Chinatown was Hong Far Low, though the sources vary as to when it was established. Various sources have suggested dates including 1875, 1879, or even 1890. The problem is that little documentary evidence has been provided to support any of these claims. Instead, the claims have taken on a life on their own, becoming "common knowledge" and then repeated by numerous other sources.

The most evidence, though still scant, was provided in the book, Chinese In Boston 1870-1965, by Wing-kai To and the Chinese Historical Society of New England (2008). Their first piece of evidence was a photo, circa 1916, of a tiled door stop that stated "Hong Far Low Established 1879." The authors thought the tiled door stop might have been created in 1896 during building reconstruction, though it's possible it was created even later. Can we trust the date on this door stop?

Another piece of evidence offered in this book is a menu from Hong Far Low, allegedly from the early 1900s, with a photo of a Chinese man, stated to be, "This is the first man in Boston who made chop suey in 1879." The name of this man was not provided. In addition, this menu is from The Harley Spiller Chinese Menu Collection, and they indicate the menu is actually circa 1930, so it wasn't from the early 1900s. The Menu lists 6 types of chicken chop suey as well as 13 other types of chop suey, including "Tomato with Beef."

Initially, we should be at least a bit skeptical of this book's evidence as it was provided only by the restaurant itself. They certainly wouldn't be the first restaurant or business to create a myth around themselves, making claims that weren't actually true. At the very least, we should seek out additional information, which could either support or refute these claims. If the claim is true, then we should expect to find additional supporting evidence through more research.

I chose to delve deeper into this question, engaging in my own extensive research into newspaper archives, old books, city directories. I published my initial article, The First Restaurants in Boston's Chinatown, in 2019, and continued my research, leading to a series of articles on the history of Chinatown and its restaurants. I've continued to expand and revise my prior articles as well as write additional ones based on my continued research. Eventually, I hope to put all of this together into a book.

Through my research, I've concluded that the evidence, most probably, does not indicate that the Hong Far Low restaurant was established in 1879, and was more likely founded about ten years later, around 1888 or 1889. In addition, if it had actually been founded in 1888 or 1889, then it definitely wasn't the first Chinese restaurant in Chinatown nor the first to serve chop suey. I didn't find any evidence to support their claim of being around since 1879.

Though the focus of this series is on Chinatown restaurants, I've included plenty of additional historical information about Chinatown for background, context and more completeness. The more we understand about the historical context and historical background of Chinatown, the better we can understand its restaurants and the community of Chinatown.

Though the focus of this series is on Chinatown restaurants, I've included plenty of additional historical information about Chinatown for background, context and more completeness. The more we understand about the historical context and historical background of Chinatown, the better we can understand its restaurants and the community of Chinatown.

Let's begin with a historical look at the first connections between Massachusetts and the Chinese, starting with trade and tea.

During most of the 18th century, Americans didn’t know much about China, but they were intrigued by the trade goods coming from China, from silks to tea. At this time, one of the most famous books about China was The General History of China by Jean-Baptiste Du Halde, a Jesuit priest. Interestingly, Jean-Baptiste never journeyed to China, compiling his book from numerous reports of other Jesuit priests who had travelled there. The book was translated into English in 1738, and it also had a powerful impact in Europe, leading to a thirst for more knowledge of China.

The British East India Company began importing tea from China in the latter half of the 17th century, though initially it was expensive. Over the course of about thirty years, the price dropped until eventually it was cheap enough for everyone, spreading tea consumption throughout the country. In addition, as the 18th century began, the East India Company had garnered a monopoly in the British Empire of trading with China.

Tea was introduced into the American colonies during the mid-17th century. Around 1650, Peter Stuyvesant, the director-general of New Amsterdam (which would become New York), introduced tea to the colony, where it became extremely popular. By the end of the century, it’s said that more tea was being drunk there than in England. During the 18th century, tea spread throughout the colonies, becoming common for all social classes, and by the middle of the century, the average colonist was consuming at least one cup of tea per day.

In general, the colonies had to purchase tea from British traders, though sometimes they bought from smugglers. And during the early 1770s, with tensions with Britain increasing, it’s said that about 75%-95% of the tea drank by colonists was smuggled into the country. Even with the Boston Tea Party and similar protests, colonists continued to drink plenty of tea, simply obtaining it elsewhere than from the British.

After the Revolutionary War, when the U.S. was no longer part of the British Empire, they were finally able to begin their own trade with China, generally selling sea otter pelts, silver, ginseng, furs, sandalwood, sea cucumbers, cotton fabric, and other items for various Chinese goods. American ships sailed around the Cape of Good Hope and Cape Horn on their way to China. U.S. received silks, porcelain, furniture, and hundreds of thousands of tons of tea.

According to When America First Met China: An Exotic History of Tea, Drugs, and Money in the Age of Sail, by Eric Jay Dolin, “The China trade was critical to the growth and success of the new nation. It bolstered America’s emerging economy, enabling Boston, New York, Philadelphia, Salem, Providence, and other ports to thrive after the ravages of the war. In doing so it helped create the nation’s first millionaires, instilled confidence in Americans in their ability to compete on the world’s stage, and spurred an explosion in shipbuilding that led to the construction of the ultimate sailing vessels—the graceful and exceedingly fast clipper ships.”

Some statistics on this China trade were provided by The Trouble with Tea by Jane T. Merritt (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2017). “All told, between 1784 and 1790, forty-one American maritime ventures exchanged goods in Canton markets; some ships, such as the Empress of China, made several voyages. Over the next decade (1791–1800) another 166 American vessels sailed directly to China.” As for the tea trade, Merritt wrote, “Into the 1790s, tea made up at least half of the cargo value for most American ships trading in China.” In addition, “Whereas Samuel Wharton had reckoned that Americans drank 2 pounds of tea annually in the 1770s, a typical family of the 1790s might purchase and drink 4 to 5 pounds each year.”

The above photograph is from the Boston Daily Globe, August 17, 1902, and the accompanying article alleged that in 1846, Oong Ar-Showe was the first Chinese man to come to Boston. Although I'll discuss the life of Ar-Showe shortly, as it's important, he actually wasn't the first to come to Boston. For the first, or at least the first for who we have documentation, we must go back about fifty years earlier, to 1796. However, we need to quickly delve another 11 years before that, to see the roots of this matter.

On September 30, 1787, Captain Robert Gray, financed by Boston merchants, sailed the Colombia Redidiva out of Boston on a trading voyage to China, first stopping in the Pacific Northwest to obtain some trade goods, such as otter pelts. The ship returned on August 9, 1790, and then left for a second voyage on September 28, 1790, reaching China in 1792 and returning to Boston in July 1793. One of the seaman on this second journey was John Boit, from Boston, who was only 15 years old and the 5th officer aboard the ship. He kept a detailed log of the voyage, of which a copy survived, providing lots of valuable information about the journey.

A year after Boit returned to Boston, when he was 19 years old, he was made the Captain of his own ship, the Union. The ship, with a crew of 22, set sail on August 1, 1794, headed to the Northwest and then onto China. After a successful journey, the ship returned to Boston in July 1796. Apparently while in China, Boit hired a Chinese servant, called Chou, who was about 15 or 16 years old, and took him back to Boston with him. It’s likely Chou lived with Boit, especially considering they were only in Boston for about a month before departing on another voyage.

Chou would thus be the first known Chinese person to live in Boston. Around this time, other Boston captains may have also hired Chinese servants, and brought them to Boston, but if so, we lack documentation. Such servants likely lived with their their employers, especially if they only spent a short time in Boston before sailing off on a new journey.

Boit was given the command of another ship, the Snow George, which departed in August 1796 to the “Isle of France,” aka Mauritius, which is located about 500-600 miles east of Madagascar. Chou accompanied Boit on this voyage. The ship arrived in March 1797, and was later sold in May 1797, after which Boit decided to spend some vacation time in Mauritius. According to The Boit Family and their Descendants by Robert Althorp Boit (1915), John Boit wrote, “Took a house on shore, attended by my faithful servant Chou (a Chinese)—kept Bachelor’s hall—and in the gay life that is generally pursued by young men on this island passed a few months away in quite an agreeable though dissipated manner.”

Sounds like Boit enjoyed quite a fun time on Mauritius, and it then appears that he returned to Boston sometime during the summer of 1798, and again, it is very likely that Chou lived with Boit in Boston at that point, especially as it would only be for a short time before tragedy took Chou. On September 11, 1798, Chou fell from the masthead of the ship Mac of Boston, though details of this accident are scant. Boit took an extraordinary step at this point, having Chou interred in the Central Burying Ground in Boston, and erecting a tombstone for him.

The epitaph read, “Here lies interred the body of Chou Mandarien. A native of China. Aged 19 years whose death was occasioned on the 11th Sept. 1798 by a fall from the masthead of the Ship Mac of Boston. This stone is erected to his memory by his affectionate master John Boit, Jr.” Chou is probably the first Chinese person buried in Boston, and you can still visit this cemetery and view his tombstone. In the epitaph, the term “Mandarien” is not intended to be a surname, but simply a term at that time meaning “Chinese.”

Although Boit called himself “master,” it doesn’t seem that Chou was a slave, but it was more a master/servant relationship. Though the burial and tombstone may create the impression that John Boit was an empathetic person, there is a darker side to this story which most sources writing about this matter omit, likely more out of ignorance than intent.

At the time of Chou's death, it appears that Boit was preparing the Mac of Boston to illegally engage in the slave trade, and if Chou had lived, he would have accompanied Boit on this expedition. The Lancaster Intelligencer (PA), September 25, 1799, reported that the Mac of Boston was condemned in the District Court of Maine for a “breach of the laws of the United States against the slave trade.” The ship apparently left Boston in November 1798, two months after the death of Chou, and allegedly was headed to Cape de Verde but Captain Boit had different plans in mind, desirous of going to Africa to purchase slaves. The crew was unaware of his plans until several weeks into the journey. Boit eventually acquired 270 slaves, male and female, and sailed to Havana, Cuba, where he sold the 220 slaves which survived the trip.

The newspaper stated, “The record of these facts, will remain an eternal monument of disgrace to mankind. A savage, who had not abjured both nature and its God, would shrink with horror at this complicated tale of crime and misery. What then shall we say of a Christian, a Bostonian, who accumulates his wealth by this nefarious and infernal traffick.” Unfortunately, I’ve so far been unable to find out what happened with this court case though it doesn't seem likely Boit received any significant punishment as he continued to captain other ships.

For example, The Boit Family and their Descendants by Robert Althorp Boit (1915) noted that Boit was married in August 1799, and “During the first years of marriage, Boit’s wife, Eleanor, lived in Newport while he was at sea; later they moved to Jamaica Plain and then Boston.” In addition, Boit made voyages on the Mount Hope from Newport, Rhode Island, to the East Indies and back in 1801-02 and 1805-6. It seems likely that if he was convicted, any punishment he received was relatively minor.

*****

In the early 19th century, there were some Chinese who, though they didn't live in Boston, passed through the city, generally as part of an exhibition, seen as curiosities. First, on August 16, 1829, the Sachem, captained by Abel Coffin, sailed into Boston Harbor, bearing with it Chang and Eng, eventually known worldwide as the “Siamese twins.” Robert Hunter, a British merchant, was also aboard, working with Coffin, hoping to financially benefit from displaying Chang and Eng to the world.

Though they were born in Thailand, Chang and Eng possessed Chinese ancestry, on both their father and mother's side, and were conjoined twins, bound at the abdomen by a five-inch long section of skin. The Boston Patriot, August 17, 1829, printed, “We have seen and examined this strange freak of nature. It is one of the greatest living curiosities we ever saw.” A number of physicians would also spend time, examining Chang and Eng. Then, Chang and Eng were exhibited at the ruins of the former Exchange Coffee House, which had burned down in 1818.

In Inseparable: The Original Siamese Twins and Their Rendezvous with American History by Yunte Huang (Liveright, 2018), it stated, “In the last week of August 1829, thousands of Bostonians, lured by a blizzard of publicity via newspaper reports, advertisements, handbills, and eye-catching posters, stood in long queues outside the tent at the Exchange, eager to get a peek at the curiosity from afar. Each of them would pay a stiff fifty-cent admission fee.” Soon after this display in Boston, Chang and Eng were taken to Providence, Rhode Island.

Another curiosity arrived in the U.S. on October 7, 1834, arriving first in New York City, allegedly the first Chinese woman to arrive in the country. She soon adopted the name of Afong Moy, and was more commonly known as the "Chinese Lady." Afong was put on display in New York City, for an admission of fifty cents, and eventually left the U.S. in 1837, only to return about ten years later. On September 7, 1847, she made an appearance in Boston, for only a 25 cent admission, for several days at the Tremont Temple.

The Boston Post, September 7, 1847, noted that she would “appear in her native costume, composed of the most superb Chinese Embroidery, and will also exhibit her magnificent Worshipping Robe!” In addition, it was mentioned that would would speak in Chinese, sing a Chinese song, and eat with chopsticks. She would also walk across the elevated stage, intended to “display (the extraordinary and peculiar characteristic of the higher classes of her countrywomen) her wonderful little feet.” At this time, the Chinese were still seen primarily as exotic curiosities.

In 1853, a troupe of "Chinese Artists" performed in Boston. The Boston Herald, March 28, 1853, printed an advertisement that a troupe of Chinese Artists would make their first appearance in Boston at the Meledeon, before they left to tour Europe. There would be “...astonishing feats of Magic, Legerdemain, Jugglery, Dexterity, & c.” The troupe had 14 performers, both male and female, children and adults. One of the noted performers was Chin Gan, a "Double-jointed Dwarf," who was 29 years old and 30 inches high. He had “...double processes in all the joints of his limbs and body” and was said to be a special favorite of the Emperor of China.

Though they were born in Thailand, Chang and Eng possessed Chinese ancestry, on both their father and mother's side, and were conjoined twins, bound at the abdomen by a five-inch long section of skin. The Boston Patriot, August 17, 1829, printed, “We have seen and examined this strange freak of nature. It is one of the greatest living curiosities we ever saw.” A number of physicians would also spend time, examining Chang and Eng. Then, Chang and Eng were exhibited at the ruins of the former Exchange Coffee House, which had burned down in 1818.

In Inseparable: The Original Siamese Twins and Their Rendezvous with American History by Yunte Huang (Liveright, 2018), it stated, “In the last week of August 1829, thousands of Bostonians, lured by a blizzard of publicity via newspaper reports, advertisements, handbills, and eye-catching posters, stood in long queues outside the tent at the Exchange, eager to get a peek at the curiosity from afar. Each of them would pay a stiff fifty-cent admission fee.” Soon after this display in Boston, Chang and Eng were taken to Providence, Rhode Island.

Another curiosity arrived in the U.S. on October 7, 1834, arriving first in New York City, allegedly the first Chinese woman to arrive in the country. She soon adopted the name of Afong Moy, and was more commonly known as the "Chinese Lady." Afong was put on display in New York City, for an admission of fifty cents, and eventually left the U.S. in 1837, only to return about ten years later. On September 7, 1847, she made an appearance in Boston, for only a 25 cent admission, for several days at the Tremont Temple.

The Boston Post, September 7, 1847, noted that she would “appear in her native costume, composed of the most superb Chinese Embroidery, and will also exhibit her magnificent Worshipping Robe!” In addition, it was mentioned that would would speak in Chinese, sing a Chinese song, and eat with chopsticks. She would also walk across the elevated stage, intended to “display (the extraordinary and peculiar characteristic of the higher classes of her countrywomen) her wonderful little feet.” At this time, the Chinese were still seen primarily as exotic curiosities.

In 1853, a troupe of "Chinese Artists" performed in Boston. The Boston Herald, March 28, 1853, printed an advertisement that a troupe of Chinese Artists would make their first appearance in Boston at the Meledeon, before they left to tour Europe. There would be “...astonishing feats of Magic, Legerdemain, Jugglery, Dexterity, & c.” The troupe had 14 performers, both male and female, children and adults. One of the noted performers was Chin Gan, a "Double-jointed Dwarf," who was 29 years old and 30 inches high. He had “...double processes in all the joints of his limbs and body” and was said to be a special favorite of the Emperor of China.

The troupe has performed in many U.S. cities, including San Francisco, Sacramento, New Orleans, St. Louis, Cincinnati, Pittsburgh, New York, Baltimore and Washington. It was said this troupe would provide “...opportunities they will furnish to obtain correct impressions concerning the peculiar character, manners and customs of a nation whose history is more remarkable and worthy of investigation than that of any other people in the world.” The cost of admission to the show was 50 cents for adults and 25 cents for children.

Another newspaper, form Louisiana, provided some more details about this troupe, so we have a better idea of what Bostonians got to experience. The Times-Picayune (LA), December 3, 1852, stated the troupe was “The great company of Chinese Jugglers, Magicians, Necromancers, Tumblers, Rope Dancers, etc.” It included performers such as Wan Sing (great Knife Thrower and legerdemain with Stone Balls), Tack Quy (famous juggler, performs The Fan & Flying Knives), Ching Moon (magician, balances on his nose Chinese coins affixed to the end of a straw), Thong Mong (stilt walking), Loi Pha (pupil of Thong Mung), Lo Pu (pupil of Thong Mung), Yan Yow (magic and legerdemain) and Chinese music by Ar Sam, Loi Pha, Lo Pa and Chin Gan.

The troupe proved so popular in Boston that the Boston Herald, April 29, 1853, reported they would also give performances at the Lyceum Hall for two nights, at the request of the residents of South Boston. They also had an afternoon matinee for children under 15 years old .

One of the next documented cases of a Chinese actually living in Boston for a time occurred during the 1840s. The Boston Globe, June 19, 1910, in an article titled, How Ah Soon Came To Boston-The Pilgrim Father of the Chinese, related the tale of Ah Soon, who initially worked as a clerk for a Chinese tea merchant in Hong Kong. One day, in 1840, when he was 17 years old, he was sent to deliver some tea chests to a Yankee ship. The captain of the ship needed a new cabin boy and decided to kidnap Ah Soon. When Ah Soon went below decks with the tea, the captain ordered the ship to set sail. Once Ah Soon realized what was happening, he asked to be returned to shore though the captain came up with an excuse why he couldn't do so, offering Ah Soon the position of cabin boy and ensuring he would be returned to China during their return trip. Ah Soon decided to accept the position, though he had little choice.

In the summer, the ship landed in Boston and Ah Soon disembarked to explore this new city. When the ship departed, Ah Soon remained behind and eventually was hired as an assistant storeman in the warehouse of a merchant who engaged in business with China. Ah Soon faced almost no prejudice in Boston, and was seen more as a curious novelty by the people of Boston. In time, he became wealthy, with a store located at 27 Union Street, and moved to the Maplewood area of Malden.

He eventually married an American woman and they had seven daughters. Since 1843, unlike a number of other states, interracial marriages in Massachusetts were legal. All of Ah Soon's daughters married Americans, as there were no Chinese men available. Sadly, just after their last daughter was married, Ah Soon's wife died, and he travelled back to China, thinking he would remain there. Two years later, he returned to the Boston area, living for another five years at his residence in Malden.

We now return to the matter of Oong Ar-Showe. In 1846, six years after the arrival of Ah Soon, Oong Ar-Showe traveled from the Chinese town of Chirmee, located about 60-70 miles from Makowe, and settled in Boston. Though he wasn't the first to come to Boston, he certainly made a significant mark in Boston, more than any other Chinese who might have predated him. There is a possibility that a few other Chinese might have come to Boston after Ah Soon, but before Ar-Showe, but we know nothing about their identities.

When Ar-Showe arrived, he was about 22 years old and spoke only a few words of English. It didn't take him long to be hired by Redding & Co., as a tea salesman. Redding & Co. had a tea shop on Washington Street, and had recently started specializing in tea. They figured that the addition of a Chinese employee might be beneficial to their business. The company also employed a woman, Louisa M. Heuss, to work with Ar-Showe, including helping him to learn English. Ar-Showe also adopted an American name, Charles.

Ar-Showe spent five years working for Redding before taking a job with P.T. Barnum, to accompany him to the World’s Fair as an interpreter for a Chinese family. Ar-Showe spent about 18 months in Europe, before returning to Boston. None of the sources I found gave any reasons why Ar-Showe would choose to leave the tea business and take a job with P.T. Barnum. Did he just want to see more of the world? Had he been made a significant financial offer? Was he bored of the tea industry?

Upon his return, sometime in 1852, Ar-Showe opened a store to sell tea and coffee, located at 21 Union St, between Hanover St and Dock Square. The Boston Post, October 1, 1852, noted the opening, and praised Ar-Showe, stating, “He has had great experience in the tea business in China, and is called the best judge of teas in this country,..” The above advertisement is from the Boston Post, June 9, 1853, and you can see that it describes eight of the teas which are available for sale at his shop. The teas were sold in five-pound bags and could be purchased at his shop or through mail order.

In addition to starting his own business, Ar-Showe decided to marry, and a wedding was held in January 28. His bride was Louisa M. Heuss, the same woman who had been his attendant when he worked for Redding & Co. The Liberator, January 28, 1853, wrote, “Oong Ar-Showe, the well known China tea merchant of Boston, was married at South Boston, on Sunday, to a young German woman. The bridegroom, for some time past, has discarded the Chinese dress, with the exception of the queue, which is kept beneath the collar of his coat, and at first sight, no one would suspect him of being a native of China.”

Ar-Showe and Louisa had a son, also called Ar-Showe though he was christened as Charles in 1854, and they would also later have two daughters. They lived in South Boston for a number of years and then moved to the Maplewood neighborhood in Malden, which is where Ar Soon also lived. Ar-Showe was an excellent businessman, acquiring a significant amount of wealth. He was naturalized as a citizen in 1860, probably the first Chinese ever to do so, and voted in every Presidential and State election afterwards. Unfortunately, his wife died in 1877 or 1878, and Ar-Showe moved back to China for two years. He returned to Malden, staying only a short time, before returning to China permanently. His children remained behind.

The year 1870 would see the first significant influx of Chinese into Massachusetts. In 1865, Chinese started to work on the construction of the transcontinental railroad, and it's said that by 1867, 90% of those railroad workers were Chinese. The completion of the railroad at the end of that decade led to significant unemployment among the Chinese. The 1870s also saw a nation-wide depression, which led many Chinese to leave California and spread across the U.S., seeking employment. Many came to the East Coast, where manufacturers were willing to hire, except that they often paid them less than they did the previous white workers the Chinese replaced.

The troupe proved so popular in Boston that the Boston Herald, April 29, 1853, reported they would also give performances at the Lyceum Hall for two nights, at the request of the residents of South Boston. They also had an afternoon matinee for children under 15 years old .

*****

In the summer, the ship landed in Boston and Ah Soon disembarked to explore this new city. When the ship departed, Ah Soon remained behind and eventually was hired as an assistant storeman in the warehouse of a merchant who engaged in business with China. Ah Soon faced almost no prejudice in Boston, and was seen more as a curious novelty by the people of Boston. In time, he became wealthy, with a store located at 27 Union Street, and moved to the Maplewood area of Malden.

He eventually married an American woman and they had seven daughters. Since 1843, unlike a number of other states, interracial marriages in Massachusetts were legal. All of Ah Soon's daughters married Americans, as there were no Chinese men available. Sadly, just after their last daughter was married, Ah Soon's wife died, and he travelled back to China, thinking he would remain there. Two years later, he returned to the Boston area, living for another five years at his residence in Malden.

We now return to the matter of Oong Ar-Showe. In 1846, six years after the arrival of Ah Soon, Oong Ar-Showe traveled from the Chinese town of Chirmee, located about 60-70 miles from Makowe, and settled in Boston. Though he wasn't the first to come to Boston, he certainly made a significant mark in Boston, more than any other Chinese who might have predated him. There is a possibility that a few other Chinese might have come to Boston after Ah Soon, but before Ar-Showe, but we know nothing about their identities.

When Ar-Showe arrived, he was about 22 years old and spoke only a few words of English. It didn't take him long to be hired by Redding & Co., as a tea salesman. Redding & Co. had a tea shop on Washington Street, and had recently started specializing in tea. They figured that the addition of a Chinese employee might be beneficial to their business. The company also employed a woman, Louisa M. Heuss, to work with Ar-Showe, including helping him to learn English. Ar-Showe also adopted an American name, Charles.

Ar-Showe spent five years working for Redding before taking a job with P.T. Barnum, to accompany him to the World’s Fair as an interpreter for a Chinese family. Ar-Showe spent about 18 months in Europe, before returning to Boston. None of the sources I found gave any reasons why Ar-Showe would choose to leave the tea business and take a job with P.T. Barnum. Did he just want to see more of the world? Had he been made a significant financial offer? Was he bored of the tea industry?

Upon his return, sometime in 1852, Ar-Showe opened a store to sell tea and coffee, located at 21 Union St, between Hanover St and Dock Square. The Boston Post, October 1, 1852, noted the opening, and praised Ar-Showe, stating, “He has had great experience in the tea business in China, and is called the best judge of teas in this country,..” The above advertisement is from the Boston Post, June 9, 1853, and you can see that it describes eight of the teas which are available for sale at his shop. The teas were sold in five-pound bags and could be purchased at his shop or through mail order.

In addition to starting his own business, Ar-Showe decided to marry, and a wedding was held in January 28. His bride was Louisa M. Heuss, the same woman who had been his attendant when he worked for Redding & Co. The Liberator, January 28, 1853, wrote, “Oong Ar-Showe, the well known China tea merchant of Boston, was married at South Boston, on Sunday, to a young German woman. The bridegroom, for some time past, has discarded the Chinese dress, with the exception of the queue, which is kept beneath the collar of his coat, and at first sight, no one would suspect him of being a native of China.”

Ar-Showe and Louisa had a son, also called Ar-Showe though he was christened as Charles in 1854, and they would also later have two daughters. They lived in South Boston for a number of years and then moved to the Maplewood neighborhood in Malden, which is where Ar Soon also lived. Ar-Showe was an excellent businessman, acquiring a significant amount of wealth. He was naturalized as a citizen in 1860, probably the first Chinese ever to do so, and voted in every Presidential and State election afterwards. Unfortunately, his wife died in 1877 or 1878, and Ar-Showe moved back to China for two years. He returned to Malden, staying only a short time, before returning to China permanently. His children remained behind.

The year 1870 would see the first significant influx of Chinese into Massachusetts. In 1865, Chinese started to work on the construction of the transcontinental railroad, and it's said that by 1867, 90% of those railroad workers were Chinese. The completion of the railroad at the end of that decade led to significant unemployment among the Chinese. The 1870s also saw a nation-wide depression, which led many Chinese to leave California and spread across the U.S., seeking employment. Many came to the East Coast, where manufacturers were willing to hire, except that they often paid them less than they did the previous white workers the Chinese replaced.

The Boston Globe, September 19, 1873, discussed some of the findings of the 1870 census. The city of Boston, with a population of 250,526, didn't have any Chinese. The communities of Brighton, Cambridge, West Roxbury and Charlestown also didn't have any Chinese. Somerville and Brookline each had a single Chinese person listed in their census results. We know there were a handful of Chinese scattered in other communities, such as Chelsea and Malden, but overall, the Chinese were clearly a rarity in most of Massachusetts.

In the far west of the state, the situation was a bit different. On June 15, 1870, 75 Chinese workers, who travelled from San Francisco, arrived in North Adams to work in a shoe factory. C.T. Sampson, the owner of the shoe factory, previously had labor difficulties with his workers, who all belonged to the Knights of St. Crispin, a trade union. The Knights were upset about the arrival of the Chinese, though they still worked at 4-5 other large shoe shops in the town. Within a week or so, the Legislature also tried to enact a law that would void any contracts with the Chinese that were for a term longer than 6 months. Fortunately, the House voted against it so it didn't come to pass.

It cost Sampson nearly $10,000 to hire and transport the 75 Chinese workers, who were mostly 16-22 years old and none had previously worked in shoe making. This group included 72 workers, 2 cooks (who were about 35 years old) and 1 foreman. The foreman was Ah Sing, who took on the name of Charlie, and had been in the U.S. for about 8 years. He was 22 years old, spoke English fluently, could read English, and was a Methodist. Of the other workers, they were divided into three companies, and each company was composed of cousins.

According to their three-year contract, the foreman was to receive $60/month for overseeing 75 men, and 50 cents more for each worker over that total. The cooks and workers was to receive $23/month for the first year, $26/month for the second and third years, and $28/month for any time after the third year. They also received room and board, and were housed at the shoe factory, with their own kitchen.

The Pittsfield Sun, August 11, 1870 reported that Sampson would soon send for 50 more Chinese workers as the initial group was working out so well, except for 4-5 of them who he might send back to San Francisco. By October 1870, Sampson claimed that he had now spent about $30,000 on his Chinese workers but he had already saved money on shoe production. In addition, the Chinese were learning English and had already sent $1600 westward, to pay off their debts, such as their original cost of passage across the Pacific Ocean. However, there is no indication at this point that Sampson followed up on his previous plan to send for 50 more workers.

The Berkshire County Eagle, December 1, 1870, noted how the Chinese workers were attending Sunday School at the shoe factory, which included learning English. Initially, a 12 year old boy, with a primer, showed up at the shoe factory to help teach the Chinese. Since then, other boys, from 12-14 years old, helped with the teaching, and some girls and older men joined them too. The Chinese integrated fairly well in North Adams and even the unions generally left them alone, primarily because the Chinese had willingly come to the shoe factory, and weren't actually slaves who had been forcibly brought there.

In the Pittsfield Sun, August 31, 1871, Sampson proudly stated that the Chinese workers had saved him about $40,000 in the past year and were producing 10% more shoes than the previous workers. And in November, Sampson noted that so far, he only had to send one Chinese worker back to San Francisco. By March 1872, one additional Chinese worker had returned to San Francisco on his own. Unfortunately, in August 1872, a 20 year old Chinese worker died, from rheumatism of the heart, and this was the first worker death. Thirty more Chinese workers came to the shoe factory in November 1872. A second Chinese worker died in February 1873, from pneumonia after two months of being ill.

The original three-year contract with the Chinese workers was set to run out in June 1873 but by the end of May 1873, all but 6 of the workers agreed to extend their contract. Those six workers generally either returned to San Francisco or China. In July 1874, there was a third worker death, from dropsy. By September 1875, there were still 93 Chinese workers at the shoe factory, so we can see that nearly all of the original workers had remained there for over five years, though that apparently changed during the next year.

The Boston Post, June 12, 1876, reported that Sampson only had 85 Chinese workers, which included 40 who had arrived a year ago. So where did approximately 50 Chinese workers go? Some likely returned to San Francisco or China, but at least a few of them may have remained in Massachusetts. The foreman, Charley Sing, was still at the shoe factory, and in October 1876, he was the first Chinaman in the area who was allowed to vote, and he opted for the Republican platform.

By February 1879, a sixth Chinese worker died, from typhoid pneumonia. A year later, in February 1880, there were only about 40-50 Chinese workers still at the shoe factory though several months later, it was noted that all of the Chinese workers would soon be gone. Some of these workers may have moved to other parts of Massachusetts though the newspapers didn't mention whether any of them so relocated.

During the 1870s, other Chinese men came to Massachusetts, including to the Boston area, and one of the first types of business that a number of them started were laundries. The first Chinese laundry in the U.S. likely opened in San Francisco in 1851 and according to New England Farmer, February 6, 1875, the first Chinese laundry in Boston, noted as a "California Chinese Laundry," had just opened at 299 Tremont Street. It was owned by Wah Lee & Co., a group of four Chinese businessmen.

A lengthy article in the Boston Daily Advertiser, February 18, 1875, went into great detail about the new Chinese laundry, as well as discussing the alleged "Chinese problem," fears of cheap Chinese labor. It began noting that the “Chinese problem” hadn’t bothered Boston yet. Even the arrival of the Chinese in North Adams, to work at the shoe factory, wasn't considered a problem. However, the writer was now concerned that Boston had “been invaded, and a veritable Chinese laundry is in successful operation in our city.”

It was feared that this Chinese laundry would cause white washing-women to go out of business, who already made barely enough money for their needs, for “wearing and exhaustive labor.” It was claimed that the Chinese charged “ruinously low charges for their work” and their “inexplicable economy of living, which allows them to live and thrive contented with these wages.” The writer then went into great detail about the operations of the Chinese laundry.

Located at 275 Tremont Street, it was mentioned to be a cheap wooden building, poorly lighted, which employed 4 Chinese workers. There was a printed list of prices and when you dropped off clothes, you received a check inscribed with Chinese characters and a duplicate was kept by the laundry. Their prices included shirts for 15 cents (or 2 for 25 cents), collar 4 cents, handkerchief 4 cents, pair stockings 5-10 cents, neckties 4 cents, table covers 15-75 cents, and overskirts 50 cents-$2.50. Clothes would also be washed and dried for 80 cents a dozen.

Clothes were taken every day of the week and returned 3-4 days later. If you want the clothes delivered to you, you simply had to pay in advance. In addition, there was “no allowance for clothes said to be lost unless reported within 24 hours after delivered." Wah Lee owned a chain of laundries, his other locations in Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, Indianapolis, Chicago, and maybe elsewhere. His other laundries were much bigger, most with about 50 employees. The laundry workers were paid about $15 a week.

By May 1875, another Chinese laundry, Sum Kee, was opened at 217 Shawmut Avenue. Others soon opened too, and the Boston Globe, August 3, 1875, noted, "The rapid increase of 'California Chinese Laundries' in Boston is noticeable."

At this time, laundry work, which was done by hand, was laborious and time-consuming, so not many whites wanted to do such work. In addition, crowded housing conditions made it more difficult for people to do their own laundry. The Chinese were willing to do so, faced little initial competition, and quickly turned it into a wide-spread industry. In addition, starting a laundry cost very little, making it attractive to the Chinese who had little starting capital. For example, it's said that in 1900, it cost about $500 to purchase a Chinese laundry. This situation was common throughout the U.S.

Commonly, these laundries had three main rooms, including the front room where customers came to drop off and pick up their laundry. A second room would be the residence while the third room would be where all the washing occurred. That stove in the washing room would also be used as their kitchen. Laundry was a laborious job, and the Chinese usually worked six days a week, and sometimes even seven. On Sundays, when they usually didn't work, they might visit and socialize with their friends and family in other parts of the city, such as eventually in Chinatown.

In September 1875, two Chinese laundries opened on Howard Street while there was mention of another Chinese laundry, owned by Wahlee Ah Gewe, at the corner of Blossom and Cambridge Streets. In January 1876, there was reference to a Chinese laundry, owned by Sing Lung and his brothers, under the Newport House at 5 Cambridge Street. In January 1878, there was mention of a Chinese laundry at the corner of Northhampton and Washington streets. And in June 1878, there was mention of another Chinese laundry at the corner of Howard and Bulfinch streets. In comparison, the Boston Globe, August 30, 1877, noted how New York had over 800 Chinese laundries. According to the Boston Daily Globe, June 18, 1878, there was another Chinese laundry located at the corner of Howard and Bulfinch streets.

Despite the proliferation of Chinese laundries, a "Chinatown" still hadn't formed in the city. The Boston Globe, December 22, 1877, published an article, The Heathen Chinee, and noted that six years ago, there were only about three or four Chinese in Boston but now there were about 150-200 Chinese. The article stated, "One thing Boston lacks which San Francisco has--Chinatown. But how long will it be before there is such a noisome quarter?" That writer definitely wasn't pleased about such an idea.

Two years later, the Boston Globe, March 25, 1879, ran another article titled, John Chinaman. How He Lives And Thrives in the Hub. The article mentioned that there were about 100 Chinese laundrymen in Boston, and a few other Chinamen, and it was alleged most were just here to earn money so they could eventually return to China. As the laundries were spread across Boston, the Chinese lived in various areas, as they usually lived in the laundry building. There still wasn't a mention of a Boston "Chinatown" or any Chinese restaurants. It also stated that there wasn't a "joss house," or Chinese temple in Boston.

There was a brief follow-up article in the Boston Globe, March 31, 1879, noting that the Chinese laundry trade had fallen off a bit, and that the owners of some of the first laundries had returned to China. The Boston Weekly Globe, September 9, 1879, went into more detail in an article titled, Washee. Washee. How John Chinaman Makes Money in Boston. The Chinese population in Boston was estimated at about 120, who were generally aged from 12-40 years, with an average of 25 years. The youngest one worked at a laundry on Leveret St, and the two oldest, around 40 years old, lived in the South End and East Boston.

About 100 of them were involved in the laundry business, working in 40 different Chinese laundries. These laundries were broken down into 30 in Boston proper, 4 in Charlestown, 3 in East Boston, and 3 in South Boston. Of those in Boston, 18 were in the South End, 10 in the West End, and 2 in the North End. The remaining 20 Chinese were involved in selling fruit, cigars, tobacco, and tea. There were several tea merchants, who had been in the city for a number of years, including Ar Showe on Union St., Ar Chang in the South End on Washington St, across from the Rockland Bank, Wong Ariock at 101 Pleasant St., and James Williams (who dropped his Chinese name) at 264 Hanover St. There was also one Chinese man with a fruit and nut store on Tremont Street.

In comparison, Sweet and Sour: Life in Chinese Family Restaurants by John Jung (Yin & Yang Press, 2018), mentioned that "The 1870 U. S. Census listed 3,653 launderers and laundresses, as the fourth leading occupation among Chinese following miners, laborers, and domestic servants, but only 66 “restaurant keepers” near the bottom of the list."

What might surprise you is that there probably were not any Chinese women living in Boston at this time. In addition, there were only a small number of Chinese woman living in other communities in Massachusetts. We know that Ah Soon had seven daughters, who married Americans, but we don't know where they settled. Ar-Showe also had two daughters and we aren't sure where they settled either, though it is possible they continued to live in Malden.

In addition, we know that one Chinese woman lived in Chelsea. In the late 1850s, Robert S. Ar Foon and his wife came to Massachusetts, where Robert acquired a job as a cook for Josiah Caldwell, a wealthy American who spent Spring in Boston, Summer and Fall in Lenox, and Winter in Cuba. Robert travelled with Caldwell for a number of years. On March 28, 1872, while living in Boston, Robert and his wife had a son, Henry Smith Ar Foon, though a couple months later they moved to Chelsea.

Prior to 1872, Robert had become a naturalized citizen, so Henry was an American citizen by birth, likely the first Chinese to achieve that honor. Robert eventually partnered with Ar Showe, the wealthy tea merchant, and opened a restaurant and ice cream café on Broadway in Chelsea. At some point, these businesses were relocated to Winnisimmet Street, and they also opened a tea shop. These businesses may have closed around 1889.

Another Chinese wife lived in Cambridge with her husband and children. On May 26, 1879, Harvard University signed a contact with Ko Kun Hua to teach Mandarin Chinese at the university. The contract was three years and Ko was to be paid $200 a month. Ko arrived in Cambridge in September, with his wife, a female servant, six children and an interpreter, Chin-Tin-Sing. His Mandarin course was intended for commercial purposes, for those planning to travel for business to China. It was open to undergraduates as well as anyone else who was interested, except for women. Initially, he had a single student, who wasn't even an undergraduate. By August 1880, this student had done so well that he left for China for business. By February 1881, Ko was instructing three students, though by the start of June, he no longer had any students. Unfortunately, In February 1882, he became ill and died from pneumonia.

In the far west of the state, the situation was a bit different. On June 15, 1870, 75 Chinese workers, who travelled from San Francisco, arrived in North Adams to work in a shoe factory. C.T. Sampson, the owner of the shoe factory, previously had labor difficulties with his workers, who all belonged to the Knights of St. Crispin, a trade union. The Knights were upset about the arrival of the Chinese, though they still worked at 4-5 other large shoe shops in the town. Within a week or so, the Legislature also tried to enact a law that would void any contracts with the Chinese that were for a term longer than 6 months. Fortunately, the House voted against it so it didn't come to pass.

It cost Sampson nearly $10,000 to hire and transport the 75 Chinese workers, who were mostly 16-22 years old and none had previously worked in shoe making. This group included 72 workers, 2 cooks (who were about 35 years old) and 1 foreman. The foreman was Ah Sing, who took on the name of Charlie, and had been in the U.S. for about 8 years. He was 22 years old, spoke English fluently, could read English, and was a Methodist. Of the other workers, they were divided into three companies, and each company was composed of cousins.

According to their three-year contract, the foreman was to receive $60/month for overseeing 75 men, and 50 cents more for each worker over that total. The cooks and workers was to receive $23/month for the first year, $26/month for the second and third years, and $28/month for any time after the third year. They also received room and board, and were housed at the shoe factory, with their own kitchen.

The Pittsfield Sun, August 11, 1870 reported that Sampson would soon send for 50 more Chinese workers as the initial group was working out so well, except for 4-5 of them who he might send back to San Francisco. By October 1870, Sampson claimed that he had now spent about $30,000 on his Chinese workers but he had already saved money on shoe production. In addition, the Chinese were learning English and had already sent $1600 westward, to pay off their debts, such as their original cost of passage across the Pacific Ocean. However, there is no indication at this point that Sampson followed up on his previous plan to send for 50 more workers.

The Berkshire County Eagle, December 1, 1870, noted how the Chinese workers were attending Sunday School at the shoe factory, which included learning English. Initially, a 12 year old boy, with a primer, showed up at the shoe factory to help teach the Chinese. Since then, other boys, from 12-14 years old, helped with the teaching, and some girls and older men joined them too. The Chinese integrated fairly well in North Adams and even the unions generally left them alone, primarily because the Chinese had willingly come to the shoe factory, and weren't actually slaves who had been forcibly brought there.

In the Pittsfield Sun, August 31, 1871, Sampson proudly stated that the Chinese workers had saved him about $40,000 in the past year and were producing 10% more shoes than the previous workers. And in November, Sampson noted that so far, he only had to send one Chinese worker back to San Francisco. By March 1872, one additional Chinese worker had returned to San Francisco on his own. Unfortunately, in August 1872, a 20 year old Chinese worker died, from rheumatism of the heart, and this was the first worker death. Thirty more Chinese workers came to the shoe factory in November 1872. A second Chinese worker died in February 1873, from pneumonia after two months of being ill.

The original three-year contract with the Chinese workers was set to run out in June 1873 but by the end of May 1873, all but 6 of the workers agreed to extend their contract. Those six workers generally either returned to San Francisco or China. In July 1874, there was a third worker death, from dropsy. By September 1875, there were still 93 Chinese workers at the shoe factory, so we can see that nearly all of the original workers had remained there for over five years, though that apparently changed during the next year.

The Boston Post, June 12, 1876, reported that Sampson only had 85 Chinese workers, which included 40 who had arrived a year ago. So where did approximately 50 Chinese workers go? Some likely returned to San Francisco or China, but at least a few of them may have remained in Massachusetts. The foreman, Charley Sing, was still at the shoe factory, and in October 1876, he was the first Chinaman in the area who was allowed to vote, and he opted for the Republican platform.

By February 1879, a sixth Chinese worker died, from typhoid pneumonia. A year later, in February 1880, there were only about 40-50 Chinese workers still at the shoe factory though several months later, it was noted that all of the Chinese workers would soon be gone. Some of these workers may have moved to other parts of Massachusetts though the newspapers didn't mention whether any of them so relocated.

During the 1870s, other Chinese men came to Massachusetts, including to the Boston area, and one of the first types of business that a number of them started were laundries. The first Chinese laundry in the U.S. likely opened in San Francisco in 1851 and according to New England Farmer, February 6, 1875, the first Chinese laundry in Boston, noted as a "California Chinese Laundry," had just opened at 299 Tremont Street. It was owned by Wah Lee & Co., a group of four Chinese businessmen.

A lengthy article in the Boston Daily Advertiser, February 18, 1875, went into great detail about the new Chinese laundry, as well as discussing the alleged "Chinese problem," fears of cheap Chinese labor. It began noting that the “Chinese problem” hadn’t bothered Boston yet. Even the arrival of the Chinese in North Adams, to work at the shoe factory, wasn't considered a problem. However, the writer was now concerned that Boston had “been invaded, and a veritable Chinese laundry is in successful operation in our city.”

It was feared that this Chinese laundry would cause white washing-women to go out of business, who already made barely enough money for their needs, for “wearing and exhaustive labor.” It was claimed that the Chinese charged “ruinously low charges for their work” and their “inexplicable economy of living, which allows them to live and thrive contented with these wages.” The writer then went into great detail about the operations of the Chinese laundry.

Located at 275 Tremont Street, it was mentioned to be a cheap wooden building, poorly lighted, which employed 4 Chinese workers. There was a printed list of prices and when you dropped off clothes, you received a check inscribed with Chinese characters and a duplicate was kept by the laundry. Their prices included shirts for 15 cents (or 2 for 25 cents), collar 4 cents, handkerchief 4 cents, pair stockings 5-10 cents, neckties 4 cents, table covers 15-75 cents, and overskirts 50 cents-$2.50. Clothes would also be washed and dried for 80 cents a dozen.

Clothes were taken every day of the week and returned 3-4 days later. If you want the clothes delivered to you, you simply had to pay in advance. In addition, there was “no allowance for clothes said to be lost unless reported within 24 hours after delivered." Wah Lee owned a chain of laundries, his other locations in Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, Indianapolis, Chicago, and maybe elsewhere. His other laundries were much bigger, most with about 50 employees. The laundry workers were paid about $15 a week.

By May 1875, another Chinese laundry, Sum Kee, was opened at 217 Shawmut Avenue. Others soon opened too, and the Boston Globe, August 3, 1875, noted, "The rapid increase of 'California Chinese Laundries' in Boston is noticeable."

Commonly, these laundries had three main rooms, including the front room where customers came to drop off and pick up their laundry. A second room would be the residence while the third room would be where all the washing occurred. That stove in the washing room would also be used as their kitchen. Laundry was a laborious job, and the Chinese usually worked six days a week, and sometimes even seven. On Sundays, when they usually didn't work, they might visit and socialize with their friends and family in other parts of the city, such as eventually in Chinatown.

In September 1875, two Chinese laundries opened on Howard Street while there was mention of another Chinese laundry, owned by Wahlee Ah Gewe, at the corner of Blossom and Cambridge Streets. In January 1876, there was reference to a Chinese laundry, owned by Sing Lung and his brothers, under the Newport House at 5 Cambridge Street. In January 1878, there was mention of a Chinese laundry at the corner of Northhampton and Washington streets. And in June 1878, there was mention of another Chinese laundry at the corner of Howard and Bulfinch streets. In comparison, the Boston Globe, August 30, 1877, noted how New York had over 800 Chinese laundries. According to the Boston Daily Globe, June 18, 1878, there was another Chinese laundry located at the corner of Howard and Bulfinch streets.

Despite the proliferation of Chinese laundries, a "Chinatown" still hadn't formed in the city. The Boston Globe, December 22, 1877, published an article, The Heathen Chinee, and noted that six years ago, there were only about three or four Chinese in Boston but now there were about 150-200 Chinese. The article stated, "One thing Boston lacks which San Francisco has--Chinatown. But how long will it be before there is such a noisome quarter?" That writer definitely wasn't pleased about such an idea.

Two years later, the Boston Globe, March 25, 1879, ran another article titled, John Chinaman. How He Lives And Thrives in the Hub. The article mentioned that there were about 100 Chinese laundrymen in Boston, and a few other Chinamen, and it was alleged most were just here to earn money so they could eventually return to China. As the laundries were spread across Boston, the Chinese lived in various areas, as they usually lived in the laundry building. There still wasn't a mention of a Boston "Chinatown" or any Chinese restaurants. It also stated that there wasn't a "joss house," or Chinese temple in Boston.

There was a brief follow-up article in the Boston Globe, March 31, 1879, noting that the Chinese laundry trade had fallen off a bit, and that the owners of some of the first laundries had returned to China. The Boston Weekly Globe, September 9, 1879, went into more detail in an article titled, Washee. Washee. How John Chinaman Makes Money in Boston. The Chinese population in Boston was estimated at about 120, who were generally aged from 12-40 years, with an average of 25 years. The youngest one worked at a laundry on Leveret St, and the two oldest, around 40 years old, lived in the South End and East Boston.

About 100 of them were involved in the laundry business, working in 40 different Chinese laundries. These laundries were broken down into 30 in Boston proper, 4 in Charlestown, 3 in East Boston, and 3 in South Boston. Of those in Boston, 18 were in the South End, 10 in the West End, and 2 in the North End. The remaining 20 Chinese were involved in selling fruit, cigars, tobacco, and tea. There were several tea merchants, who had been in the city for a number of years, including Ar Showe on Union St., Ar Chang in the South End on Washington St, across from the Rockland Bank, Wong Ariock at 101 Pleasant St., and James Williams (who dropped his Chinese name) at 264 Hanover St. There was also one Chinese man with a fruit and nut store on Tremont Street.

In comparison, Sweet and Sour: Life in Chinese Family Restaurants by John Jung (Yin & Yang Press, 2018), mentioned that "The 1870 U. S. Census listed 3,653 launderers and laundresses, as the fourth leading occupation among Chinese following miners, laborers, and domestic servants, but only 66 “restaurant keepers” near the bottom of the list."

What might surprise you is that there probably were not any Chinese women living in Boston at this time. In addition, there were only a small number of Chinese woman living in other communities in Massachusetts. We know that Ah Soon had seven daughters, who married Americans, but we don't know where they settled. Ar-Showe also had two daughters and we aren't sure where they settled either, though it is possible they continued to live in Malden.

In addition, we know that one Chinese woman lived in Chelsea. In the late 1850s, Robert S. Ar Foon and his wife came to Massachusetts, where Robert acquired a job as a cook for Josiah Caldwell, a wealthy American who spent Spring in Boston, Summer and Fall in Lenox, and Winter in Cuba. Robert travelled with Caldwell for a number of years. On March 28, 1872, while living in Boston, Robert and his wife had a son, Henry Smith Ar Foon, though a couple months later they moved to Chelsea.

Prior to 1872, Robert had become a naturalized citizen, so Henry was an American citizen by birth, likely the first Chinese to achieve that honor. Robert eventually partnered with Ar Showe, the wealthy tea merchant, and opened a restaurant and ice cream café on Broadway in Chelsea. At some point, these businesses were relocated to Winnisimmet Street, and they also opened a tea shop. These businesses may have closed around 1889.

Another Chinese wife lived in Cambridge with her husband and children. On May 26, 1879, Harvard University signed a contact with Ko Kun Hua to teach Mandarin Chinese at the university. The contract was three years and Ko was to be paid $200 a month. Ko arrived in Cambridge in September, with his wife, a female servant, six children and an interpreter, Chin-Tin-Sing. His Mandarin course was intended for commercial purposes, for those planning to travel for business to China. It was open to undergraduates as well as anyone else who was interested, except for women. Initially, he had a single student, who wasn't even an undergraduate. By August 1880, this student had done so well that he left for China for business. By February 1881, Ko was instructing three students, though by the start of June, he no longer had any students. Unfortunately, In February 1882, he became ill and died from pneumonia.

By 1900, there were only about 12 Chinese women living in Chinatown, with over 2000-3000 men. These women were generally the wives of merchants, and they were often very traditional, remaining in their homes most of the time, rarely seen by anyone but their husbands. In other Chinatowns around the country, there were significantly more Chinese women than in Boston, but that also led to additional problems that Boston never experienced.

In San Francisco, far more Chinese women came to the city, but the majority of them ended up as prostitutes, nearly all of them as sex slaves, and it should be noted that prostitution was not illegal at that time. For example, in 1870, there were about 2,000 Chinese women in the city, and 71% of them were identified as working as prostitutes.

There are multiple reasons why so few Chinese women came to the U.S. at this time. First, many Chinese men came to the U.S. to make money, with plans to return to China once they had made a sufficient amount. It wasn't cheap to travel across the Pacific and would have been much more expensive for them to travel with their wives. U.S. law also eventually placed barriers upon Chinese women from entering the U.S. In 1880, the ratio of Chinese men to women was at 21:1, rising to 27:1 in 1890. This large disparity between Chinese men and women would last into the 20th century.

With so few Chinese woman in the Boston area, a number of Chinese men would eventually marry white women. Probably the first white woman to live in Chinatown, and marry a Chinese man, was a woman known as Bella, and she soon acquired the title of Queen of Chinatown. Bella arrived in Chinatown sometime around 1880-1882 and trying to determine the facts of her history before she arrived in Boston isn't easy. Bella may not have even been her birth name.

For example, the Boston Sunday Post, March 31, 1901, claimed that her prior name was “Oklahoma Belle,” which she acquired from her time as a bareback rider in the circus. In addition, she was supposed to be a doctor, having graduated from a medical college in Poughkeepsie. She was also now supposedly providing medical care for the Chinese. Much of this wasn't mentioned again in any other newspapers and can't be confirmed, except that a later newspaper specifically stated she never completed any medical studies.

Later, the Boston Globe, May 15, 1906, printed that Bella was an Englishwoman, who came to New York when she was very young. She eventually married a "renegade sailor," a white man and when he died, she moved to Boston. There was no mention that she was a doctor or had even been a bareback rider.

We know that Bella married Yuen Song (also known as Wee Yuen) prior to 1889, and likely during the early 1880s, and they lived at 29 Harrison Avenue, a residence that Bella would remain in throughout her entire life. In the Boston Daily Globe, June 13, 1889, the police stated, during an opium investigation, that “There is one white woman in Chinatown but as she is legally married to a Chinaman, the police could not molest her.” Though Bella isn't mentioned by name, it seems clear that it refers to her. As Bella might have been the only woman in Chinatown at this time, it's not too surprising that she was popular and would receive the designation of Queen of Chinatown, a role she apparently relished greatly.

Six years later, the police finally chose to move against Bella in a new opium investigation. The Boston Daily Globe, May 13, 1895, noted that the police made a raid on her residence, as they had information that it was an alleged opium joint. The police found plenty of opium, pipes and other paraphernalia, was well as four other Chinese men who had been partaking. Yuen and Bella were arrested, though the ultimate disposition was not mentioned. Based on similar cases at this time, they might have been able to pay a small fine to resolve the matter.

The Boston Sunday Post, March 31, 1901, referred to Bella as the Queen of Chinatown, and noted that she was now married to a second Chinese man, Jim Gong, who was dying of consumption. But, from the previous 1895 article, it seems that her marriage to Jim wasn't contemporary to this article.

An article in the Boston Sunday Post, September 13, 1903, discussed that a number of white women had married Chinese men, noting that there were only 14 Chinese women living in Boston. “The police say that these mixed marriages rarely result in trouble. The white woman usually bosses the outfit and is careful to do nothing that would attract the attention of the police. She keeps her husband out of trouble and, as a general rule, is devoted to him.” The article also stated that none of these wives would dare anger or oppose Bella, the Queen of Chinatown.

Bella's residence was raided again, this time for illegal gambling rather than opium. The Boston Post, August 15, 1904, reported that in an adjoining room to Bella’s residence, the police were found "Chinese playing picu." They were arrested for the crime of “gaming on the Lord’s day,” a crime which was enforced numerous times, especially against the Chinese.

In the Boston Globe, August 23, 1905 and Boston Sunday Post, August 27, 1905, there was discussion that Bella Long, the Queen of Chinatown, might marry for the 4th time. Her third husband, Jim Long, also known as Ah Long, who had been a gambler, had died about a month ago. Her new beau appeared to be "Jim the Guide," who did guided tours of Chinatown, and his last name wasn't known by any of the reporters. The Globe article also mentioned that Bella was about 45 years old, still an opium smoker, and that in a racist comment, “She has lived among Chinamen so long that it seems as though her eyes had grown on a slant.”

Unfortunately, like her third husband, Bella was the victim of tuberculosis. According to the Boston Herald, December 23, 1905, the board of health viewed her as a health menace and had her removed to the Long Island Hospital. Bella didn't resist the removal. The newspaper noted, "She has been the Chinamen's acute adviser. She was true blue. She could be trusted. To her they turned when danger threatened and they found themselves at a disadvantage because of their inability to speak English fluently."

The article also mentioned how she mainly remained in her apartment, which was described as "dark, dirty, ill-ventilated and choky with the fumes of opium." As the officers came to take her to the hospital, she became chatty, talking about her life. She claimed to have been smoking opium for about 26 years, having started when she was 17 years old. Her original home was allegedly in Hudson, New York, though she eventually moved to New York City. While in NYC, when she was 17, she and a cousin went to the a theater and later stopped in an opium den. She spent seven weeks in NYC, before returning to Hudson, continuing to smoke opium, and became an addict. The opium sapped her ambitions, including her desire to study medicine.

In New York, she married her first husband, who was lost at sea while racing a yacht from New York to Ireland. Then, while living on Pell Street in NYC, she married a jealous Chinese man, who eventually tried to kill her. He was convicted and sentenced to 10 years, though Bella pled for leniency so he only served eighteen months. Once he was released from prison, they moved to Boston, where he died. The article also noted her name was once Bella Hubbell, though it isn't clear if that was her maiden name or her first married name.

Bella also claimed to have been related to the Coffins of Nantucket. In addition, she stated that her father was still living in Jersey City. She claimed to still have wealthy and powerful friends, but she was a slave to the opium pipe and it guided her life. And it is clear that she never married Jim the Guide.

The Boston Herald, May 1, 1906, stated that Bella was dying, and probably only has days remaining. She had been a good patient, and received many Chinese visitors from Boston, some bringing her news, others seeking her advice. The doctors also felt that some of the visitors were bringing her opium, though they tried to deter it. This article also makes it clear that her maiden name was Bella Hubbell.

The Boston Globe, May 15, 1906 reported that Bella had died of consumption. When she arrived in Chinatown, she was young and pretty, and quickly a big hit in that neighborhood. She used to give audiences in her home at 29 Harrison Avenue, often reclining on her couch, smoking opium, though also warning people about the dangers of opium. The Boston Post, May 16, 1906, reported that Bella Long would be buried quietly and was unable to receive a Chinese funeral as her ancestors didn’t lie honored in Chinese graves. What is also interesting to note is that Hong Far Low, a leading restaurant manager, had acted as Bella’s prime minister.

A bit more information about Bella was presented in the Boston Herald, July 16, 1929. The newspaper spoke to a British musician, W.F. Cooper, who claimed to have met Bella back in 1903. He had heard stories that Bella subsisted only on tobacco, about two pounds a day. When he met Bella, she confirmed this story to him. However, he either misunderstood or was intentionally misled, as Bella smoked opium, not tobacco. The article also mentions that after Bella's death, her apartment became a tourist attraction, which cost people 50 cents to visit and view.

At this point, before progressing further, I should mention a dark aspect of American history, involving abject racism against the Chinese.

The boys had been mutilated and the article noted: “Through the left side of the neck were two dagger thrusts, another through the side of the left cheek, given with such force as to knock out the under double teeth. The queue has been cut off, the spinal column severed and the head nearly cut off.” And in addition, "according to the custom prevailing in China" the killer had "drawn the knife deeply across the stomach.” It was believed that the killer had first attacked the victim while he was sleeping. A few Chinese told the police that the victim had potentially violated the laws of a Chinese secret society.

The Boston Globe, July 19, 1886, provided more details, noting that Ding Chong, who was about 50 years old, had come to Boston six years ago. He started working for Quong at his laundry, and the three years later, he bought the laundry from Quong who returned to China. Ding was polite and friendly, and about a month ago, he told some friends that he had $400, and would soon sell his laundry and return to China, where he had a wife and child.

There was another article about Chinese New Year in the Boston Globe, January 30, 1889, and it mentioned how Moy Auk and his band came from New York City to play at the celebrations. Based on other information, it appears Moy Auk chose to settle into Chinatown at this time, thinking he might be able to make a living with his band. This article also mentioned two restaurants in Chinatown, located at #26 Harrison and #88 1/2 Harrison Avenue. No names were provided for the restaurant or their owners. These also appear to have been the only two restaurants in Chinatown at this time, and Hong Far Low was not located at either of those addresses. This seems to indicate that Hong Far Low did not yet exist.

Moy Auk finally decided to get involved in food in Chinatown. The Boston Globe, June 11, 1889, reported on a banquet celebration of the Chinese Free Masons, which was held at their hall on 36 Harrison Avenue. The caterer and chief cook of this banquet, for about 500 people, was Moy Auk, who also led the band. It wasn't clear in this article whether Moy Auk actually ran a Chinese restaurant or was more just a caterer.

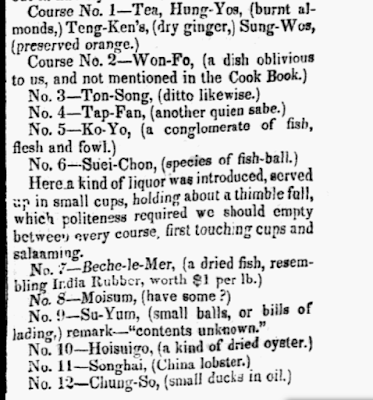

More information about Moy was provided in the Boston Globe, June 23, 1889. The article, titled Chinese Restaurants, indicated that there were six Chinese restaurants in Chinatown. There had been a "swell" Chinese restaurant at #24 Harrison Avenue, just over the store of the Quong Hing Wah Company, but the restaurant owner was a serious gambler. He lost much too much money and the restaurant had to close. The article then mentioned that the two best Chinese restaurants were now Moy Auk's at 36 Harrison Avenue and Hong Far Low at 38 1/2 Harrison Avenue. So, Moy had actually started a restaurant and wasn't just a caterer.

This is the first newspaper reference to Hong Far Low I found, and very little information was provided about it, except that it had an English painted sign that could be seen from the street. For how long had Hong Far Low been in business, considering it had a reputation as one of the best in Chinatown? The article doesn't answer that question though we can look through the lens of the other best restaurant, Moy Auk, which featured as the main topic of this newspaper article.

Moy was referred to as the "Delmonico's of the Celestials in this city." At this time, Delmonico's, in Manhattan, was considered one of the finest restaurants in the country so this was very high praise. Moy came to Boston, hoping to be able to play music year round, but learned that wasn't possible so he decided to open a restaurant. The talented Moy was a butcher, meat cook, and pastry chef. His restaurant, which was located beneath the hall of the Free Masons, was where the Chinese celebrities and dignitaries dined, as well as some white men, for a dish of "chop sui."

The article also stated that "Chop siu is Chinese for mixture, and it is a mixture which proved to be excellent eating. It is composed of chickens' and ducks' livers, gizzards and hearts cut into small pieces, fresh pork, celery, asparagus tops, bamboo shoots, and one or two other Chinese vegetables or greens, and dried mushrooms. These are all cut up into convenient pieces for the mouth, some sort of gravy is poured over the mass, which is then put in a spider and fried. While cooking the mixture sends out a very savory odor, and although its appearance on the table is rather against it, it is, nevertheless, very palatable." There isn't any mention that Hong Far Low was the first to bring chop sui to Chinatown, which casts doubt on their claim.

Moy's great culinary fame apparently arose within a time span of less than six months, so it wouldn't be a stretch to believe that Hong Far Low had also been in existence for less than six months. However, Hong Far Low hadn't garnered the same culinary recognition, though it was still seen as one of the best restaurants in Chinatown. If Hong Far Low had been in operation since 1879, you would likely assume that it would have been considered the premiere restaurant in Chinatown in 1889. In addition, the lack of any prior mention in the newspapers of the existence of Hong Far Low before 1889 casts more doubt on their claim to have been established in 1879.

As a follow-up to this article, the Boston Globe, June 30, 1889, wrote that Moy Auk was very pleased with the write-up review of his restaurant. Moy just wanted to correct one point, that he did not generally keep chickens in the back of the kitchen, except for a single rooster at any time. His chickens, hundreds of them, were raised at his place in Winter Hill.

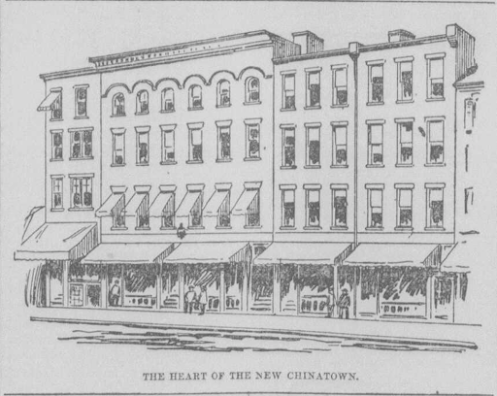

More details were provided in the Boston Globe, February 20, 1893, including the above diagram of the proposed street changes. The article was titled, "Boston's Chinese Quarter. It's Squalor and Bad Sanitary Condition--Room Wanted for Rapid Transit." A city official stated, "The section of our city popularly known as 'Chinatown' is fast becoming one of the most valuable pieces of real estate in Boston." Chinatown was surrounded on three sides by "big and costly business blocks" and Chinatown was considered "huddled and congested." The price of widening Harrison Avenue had now increased to $400,000.