Finally, the article briefly discussed

Andrew A. Badaracco, a Councilman who was the first Italian representative in an elective office. He was also a business man of good standing, and it was said, “

In his political office, as among his business acquaintances, he is respected as a man of honor and integrity.”

Where did the North End get its groceries? The

Boston Globe, October 28, 1900, stated that “

Little Italy is full of ‘grosserias’ or Neapolitan and Genoese ‘botteghe,’ that sell all kinds of Italian provisions.” Most of those shops were supplied by New York farms, or received imports from Italy.

“But the most prosperous ‘grosseria’ in the North end is the one exception that proves this rule, since it is supplied in all these particulars by the products of an Italian farm in Milford, Mass.”

This farm was owned by Sig Enrico Tasinari, a prosperous Italian from Bologna, although the farm was originally owned by Bernardo Ambrosoli. Upon Bernardo's death, the farm was put up for auction and Tasinari bought the buildings and 85 acres of farmland. He even grows some grapes there, to make “vino nero,” black wine.

Italians and Thanksgiving! The Boston Herald, November 30, 1900, reported that Thanksgiving had been celebrated in Little Italy. It was said, “fat, brown, juicy turkeys were on nearly all the Italian dinner tables. It was a home day, and the Northenders ate at home and entertained at home, there being no society parades, banquets or concerts.” In addition, “There were feasts, however, at the Hotel Italy in North square and the Hotel Piscopo on Fleet street.” The article continued, “The Italians do not do things by halves. They began their feasting and celebrating early yesterday morning and did not stop until this morning. It was a lively and picturesque night in the North end, and there was nothing to mar its pleasures.”

Bad news for the hotels in Little Italy. The Boston Herald, December 5, 1900, reported that the highest court in Massachusetts had declared that licensed inn holders could not serve alcohol after 11pm. This was a serious problem as most inn holders claimed that their best business occurred between 11pm and 1am. “In that part of the city known as ‘Little Italy’ the enforcement of the law will result in great hardship, and Hotel Italy and Hotel Piscopo will suffer to a considerable degree.”

The Boston Globe, December 16, 1900, had a brief mention of Damiano’s Italian restaurant in the North End.

A terrible fire! The Boston Herald, January 30, 1902, reported about a disastrous fire at 8 Fleet Street where 9 people died, all but one being Italian, and numerous others injured. The Boston Herald, January 31, 1902, added that the cause of the fire still unknown, but it was possibly arson. However, there weren't any subsequent newspapers revealing whether it was arson or not.

Would you have expected a book store in Little Italy at this time? The Sunday Herald, July 6, 1902, discussed a book shop that existed on North Street. “For ‘Little Italy,’ strange as it may seem, is very fond of reading, and although these Italians can scarcely be called literary, still they love stories; folk legends they have heard all their lives, tales of ghosts and bitter vendettas and histories of the saints. All these and also many better known books are to be found on the shelves of this little ‘libreria,’ piled in high heaps that reach to the ceiling.” The book store had a sign “Assolutamente Proibito di Fumare,” meaning "smoking is absolutely prohibited."

There were books “to suit all tastes,” including "for cooks books of delicious rules for ‘minestra,’ ‘crema fritta,’ ‘raviole,’ or any of the thousand good things that ‘Little Italy’ loves,…” There were also plenty of “goody-goody books for children.”,moral stories to make children better adults. The article also mentioned, “Usually it is the northern Italian who is better read, as he is better bred, but this little ‘libreria’ is able to satisfy all tastes with its varied stock,….”

Cards and hotels. The Boston Herald, August 16, 1902, first mentioned that local Italians were happy over rumors that the police would allow them to play cards in bar-rooms, “in plain sight from the street” as they once did. It's unclear if this actually came to fruition or not.

The article then mentioned that two hotels were supposed to reopen in the North End, including the hotel of Ambrosoli, located on North Street just south of North square, and the Hotel Italy in North Square. However, it was claimed that the hotels were being opened by men from New York. Men from Boston had tried to reopen the hotels, but had been repeatedly denied liquor licenses. The local Italians used to frequent the hotels, playing cards, talking and drinking. “The Italians argue that they are entitled to hotels, and they prefer to associate with their own and to keep by themselves in places where the food, the cooking, the drinks and all the customs are distinctly Italian.”

Running amok in the North End! The Boston Herald, August 21, 1902, reported that previous night, on Richmond Street, Maurice Higgins, 34 years old, a steamship fireman, ran amok. It was said that he was not drunk and no one understood the reason for his erratic behavior. However, he attacked and knocked down at least 6 people, including a 50 year old women, who received a broken nose, abrasions and contusions. A large crowd, of several hundred, trailed him, some carrying with revolvers and knives. Fortunately, the police arrived and arrested him before the crowd could inflict its own version of justice on the crazed man.

Another murder in an Italian restaurant! The Boston Herald, February 18, 1903, reported that Vincenzo Penta, a contractor, was slain by Beningno Santosusso, a laborer, in an Italian restaurant on Moon Street in the North End. “It was another case of an Italian cutting affray, for which the North end is famous, differing from the ordinary cases only in detail and in the capture of the alleged murderer.”; The restaurant, owned by Alesandro Servitella, was located in the basement of the dwelling house at 20 Moon Street, only a block away from a fatal shooting from last week. Penta entered the restaurant, just to start a fight with Santosusso, and insulting him before striking him a couple times. Then, it seems Santosusso used a knife, killing Penta and he fled.

"Don’t Snub the Spaghetti.” That was the title of an article in the Boston Post, December 20, 1903. The article stated that people dined at Italian restaurants for the spaghetti. However, it was claimed that you never knew when you would receive the spaghetti during the meal. However, the article then claimed that the only way to surprise the employees and other patrons was to declare “I don’t care for spaghetti! Take it away.”

A lengthy article about North End's Italian restaurants appeared in 1904. The Boston Herald, February 21, 1904, stated, "If you are very hungry some day when you want a good, substantial dinner, and your pocket is unfortunately low, then go to Little Italy." There were details about a Tuscan restaurant, kept by Bimbo Funai, who claimed to be from Florence. He brings the crusty bread and unsalted butter to your table. Some of the dishes he serves includes polenta, minestra, scalpina alla marsala (onions and veal), and a variety of garlic flavored dishes. "In the Tuscan restaurant you will meet all classes of men, and all trades. Bimbo has no prejudices."

Enrico Tassanari was the proprietor of the Bolognese restaurant, and might have been the wealthiest man in Little Italy. His restaurant is described as a "long smoky room, hung with strings of dried mushrooms and garlic and peppers, the low, dark wine-stained tables, and the cheese-piled counter behind which the pretty Italian girls stand to serve out smiles and spaghetti." This is a more formal restaurant than that of Bimbo. The menu is on a chalkboard, and you will see items like pig's feet, spaghetti and boiled cabbage.

There is also Leveroni's Genoese restaurant, and their menu was printed on paper. He serves dishes such as tagliarini shredded with mushrooms and garlic spiked ravioli.

The article then differentiates between Northern and Southern Italian restaurants. "Beyond doubt the best restaurants are kept by northern Italians, and while southern Italy makes the music, the northerners cook the food." And the article ends with, "Nowhere else can you dine so nicely and so well, so abundantly and so cheaply as in Little Italy,..."

***************

The Boston Globe, March 5, 1904, reported that Vincent and Catherine Tassinari had applied for a liquor license as Victuallers and Wholesale dealers at 148 North Street. This location once used to be the Hotel Ambrosoli. However, two years later, the Boston Globe, August 10, 1906, noted others were now seeking a liquor license for this location. Carmine Paglinca and Gaetano Balboni applied for a liquor license as Victuallers and Wholesale dealers.

Another death in a restaurant. The Boston Globe, June 8, 1908, reported on an incident at the restaurant of G. Paglianca (probably a spelling error) at 148 North Street. One of the cooks was Antonio Pinotti, a very jealous man who constantly fought with his wife. This time, he shot his wife and then shot and killed himself. Although his wife survived at first, she died two days later of the gun shot wounds.

The Boston Globe, March 1, 1912, reported that Carmine Paglinca and Josie Luongo had applied for a liquor license as Victuallers at 148 North Street.

An assault on Carmine! The Boston Globe, August 13, 1912, reported that two young men assaulted Carmine Paglinca in his saloon at 148 North St. One of them actually attempted to shoot Carmine, but the gun was wrestled away from him before he could fire. The two young men were both arrested.

The Boston Globe, March 1, 1912, reported that Carmine Paglinca and Sylvia Paglinca had applied for a liquor license as Victuallers at 148 North Street.

Carmine was assaulted again! The Boston Globe, June 25, 1913, reported that at Municipal Court, it was learned that Carmine Paglinca, who owns a saloon and pool hall at 148 North St., was stabbed twice in the last six months. He was stabbed twice by Lugi Paprida, age 27. In the current case, Carmine had been stabbed in his left shoulder and left leg. Carmine is related to Lugi through marriage, but the two have been unfriendly for a long time. Six months ago, Lugi was found guilty of assault for stabbing Carmine, fined $25 and placed on six months probation. In the current case, the matter was sent to the Grand Jury.

The outcome of this case wasn't mentioned in the newspapers, and Paglinca's saloon also stopped being mentioned. It's possible Carmine chose to close the saloon after this second stabbing.

***************

Another shooting at an Italian restaurant! The Boston Journal, November 7, 1904, reported on a shooting at an Italian restaurant, owned by Antonio Liberatori, at 7 Prince Street. Ernest Alesso, 30 years old, was a waiter at the restaurant. Giovanni Pisano, age 32, ordered some pies, but when he learned how long he would have to wait, he decided to leave and not pay. He got into a "scrimmage" with Alesso, who retrieved a revolver from behind a counter and fired three shots at Pisano, hitting him in the right cheek, shoulder and abdomen. A Help Wanted ad in the Boston Globe, February 28, 1902, sought 2 waitresses, so it seems this location was a restaurant at this time. It's unclear whether Liberatori owned the restaurant at that time or not.

The Boston Herald, July 12, 1905, reported that Tony Leonardi, age 40, an Italian restaurant owner, the proprietor at 212 North Street, drowned in Lake Chebacco near Essex. Tony came to America when he was fifteen and “amassed a comfortable fortune.” He used to live at 294 Hanover Street.

***************

A new hotel with Italian cuisine opens. The

Boston Evening Transcript, January 11, 1905, printed an ad for a new hotel, the

Hotel Napoli, which was supposed to open the next day. It was located at 84-90 Friend Street and offered, "

Strictly First Class Italian Cuisine."

The

Boston Evening Transcript, February 4, 1905, had another ad which provided more information. The hotel served both French and Italian cuisine, and offered a Lunch with wine for 40 cents and dinner with wine for 75 cents. The proprietors were

Di Pesa & McCulloch, and the manager was

William Maturo.

The

Boston Evening Transcript, September 29, 1906, published an ad for the

Hotel Napoli, with a "

high-class" French and Italian restaurant, located at 84-90 Friend Street. It was an “

Up to date Bohemian Resort…,” that offered “

Genuine Italian Spaghetti cooked in a hundred different styles.”

The Boston Evening Transcript, November 27, 1906, also had an ad for the Hotel Napoli, stating it was "the only high-class Italian restaurant in Boston.” It also stated, "The cuisine is modeled after the most celebrated cafes in Italy---." The proprietor was M. Di Pesa & Son, and their specialty was "a Neapolitan Meal served in Neapolitan style."

The Boston Evening Transcript, December 26, 1906, noted that Marciano DiPesa, George E. McCulloch, and Alfred DiPesa, as M. DiPesa and Co., had applied for a liquor license as inn holders for the time from 11pm-Midnight. This was part of the city's new "midnight laws", extending the time when serving alcohol could be served.

The Boston Journal, October 24, 1908, had an advertisement for the Hotel Napoli, with an address of 84-96 Friend Street. “The Hotel Napoli is the only high-class Italian restaurant in Boston. The cuisine is modeled after the most celebrated cafes in Italy—an entrancing spot that seems to have been transplanted from Naples to the heart of Boston. Our specialty is a Neapolitan Meal served in Neapolitan style.” The proprietors were M. Di Pesa & Son.

The

Boston Herald, December 14, 1908, had another ad for Hotel Napoli, noting its Table d’Hote Dinner with Chianti for only 75 cents. The dining room has also been remodeled and redecorated. They also stated, "

We claim it to be the only high class Italian restaurant in Boston,..."

A remodeled Cafe. The Boston Evening Transcript, December 16, 1908, mentioned that the Italian cafe at the Hotel Napoli was now open after months of preparation. It had once been a Bohemian resort but had been transformed into a Renaissance dining-room. The entire lower floor of the hotel has now been given over to the restaurant, and it will now seat about 400 people.

During the next few years, the Hotel Napoli would be mentioned numerous times as a place for various groups to celebrate and dine at the cafe.

Milk crimes! The Boston Evening Transcript, May 2, 1911, reported that Alfred Di Pesa of the Hotel Napoli had been fined $10 for "offering milk for sale which was not up to standard." He was not the only one fined for a violation of this regulation.

The Boston Evening Transcript, November 27, 1912, had a brief article that stated, "The Napoli has wide recognition as an Italian restaurant of the highest class and discriminating patrons of public dining rooms may frequently be found around its tables. Its table d'hote luncheons and dinners long have been popular because of the excellence of its food, its variety and the good service, always an essential factor in satisfactory dining."

Murder! The Boston Globe, May 21, 1913, reported William Janino, age 21, shot and killed Mrs. Margaret Pollack in the Hotel Napoli, before turning the gun on himself. Apparently, William had planned to marry Margaret within a day or two, but then suddenly learned that she was already married.

Ten years after its opening, in October 1915, the Hotel Napoli offered a lunch table d'hote for 50 cents and a dinner for 75 cents. The price of lunch had risen only 10 cents and the price of dinner had remained the same.

The Boston Globe, September 18, 1920, reported that the Hotel Napoli property had been acquired by the B&M Railroad Department of the Y.M.C.A. and it would be renovated and furnished. This would be a temporary home for the Y.M.C.A. as they are working on plans for a big new clubhouse. Thus, the Hotel Napoli closed, after fifteen years.

However, a

Napoli Restaurant then opened on Friend Street, and the Boston Post, October 8, 1920, posted a little ad for this new restaurant.

The

Boston Post, April 18, 1921, made it clear that this restaurant had replaced the Hotel Napoli. The ad indicated the Grand Opening of their Italian Pavilion, and that the managers included

Giulio Labadini and

Louis W. Scotti.

The Boston Post, August 11, 1921, briefly indicated that the proprietor of the Napoli was Joseph di Pesa.

A Prohibition raid! The Boston Globe, May 5, 1922, reported that Prohibition agents raided the Napoli Restaurant during their luncheon, when there were about 40 diners there. The agents ended up arresting 10 people, including three diners, for illegal possession of alcohol. Others arrested included Gaetano Spinelli, the chef and maybe a part-owner, and three waiters. The Boston Globe, May 6, then provided more details. The Feds had heard that wine was being served at the restaurant in coffee cups. It was said a bottle of wine could be purchased for $2.25. The wine cellar was searched and alcohol was confiscated, including moonshine.

The Boston Globe, May 7, 1922, reported that the diners were discharged in court, although they were to appear as material witnesses, while the alleged proprietors were held in $500 for a hearing on May 12. The proprietors were alleged to be Gaetano Spinelli, Giulio Labadini and Louis W. Scotti. The waiters were held on various charges of selling and possessing.

The Boston Globe, May 24, 1922, reported on a hearing that day where it was questioned the right of the Prohibition Enforcement Supervisors James Roberts to inform Arthur Davis, head of the local Anti-Saloon League, of the raid on the Napoli. Commissioner Hayes stated that Roberts had no right to invite anyone except for his agents. The charges against Louis W. Scotti were dismissed, and the hearing for the other two defendants would take place later that day.

The hearing took place on May 24 and May 25, and was then continued for a week. The Boston Globe, June 5, 1922, then announced the ruling of Commissioner Hayes, which dismissed the charges about Spinelli and Labadini. The Commissioner stated that the Prohibition agents were trespassers and that the evidence they found at the restaurant was illegally secured. The agents smashed down the door, which the Commissioner found to be an abuse of their search warrant, and thus they were trespassers.

Bankruptcy! The Boston Globe, May 5, 1925, noted that Napoli Restaurant had been forced into an involuntary bankruptcy by its creditors, and it appears this led to the closure of the restaurant.

***************

Another new Italian spot. The

Sunday Herald, October 7, 1906, had an ad for the

Lombardy Inn, an Italian restaurant located at 1 Boylston Place, near the Colonial Theatre. It was set to open on October 10. It offered "

Strictly Italian Cuisine" with "

Italian and French Wines." More detail was provided in the

Boston Herald, October 20, 1906, which noted that 1 Boylston Place had been leased to

Michael F. Dillon and

Emilie Columbo Dillon, to become The Lombardy Inn.

The Boston Globe, March 9, 1907, mentioned that Michael F. Dillon and Emilie C. Dillon, had applied for liquor licenses as a Victualler and Wholesale Dealers for the Lombardy Inn. This was repeated in March 1908.

The Boston Herald, September 27, 1908, noted that the Lombardy Inn, at 1 and 2 Boylston Place, had recently conducted extensive alterations and would reopen on September 30.

***************

Around 1910, the population of the North End was nearly 30,000, a rise of approximately 5,000 people in the last ten years. However, now Italians constituted about 28,000 people, with only a tiny percentage of non-Italians choosing to remain in the neighborhood.

The

Boston Herald, April 24, 1910, had an ad for the Lombardy Inn, at 1 and 3 Boylston Place, stating it was a "

rendezvous for epicures."

The

Boston Evening Transcript, October 18, 1913, printed the above ad, claiming it was "

Boston's Most Unique and Interesting Cafe and Restaurant."

The Boston Evening Transcript, January 12, 1914, had a brief section on the Lombardy Inn, noting, "It is away from the noise and bustle of the city and is a high-class Italian restaurant. Surrounded with a genuinely Bohemian atmosphere and located in the theatrical district, the place offers the discriminating diner the excellent dishes and wines, with Italian cooking."

A new hotel! The

Boston Evening Transcript, October 2, 1915, had an advertisement announcing the opening of a new hotel at the Lombardy Inn, with numerous alterations intended to make it "

attractive and comfortable."

Four years later, bankruptcy! The

Boston Globe, December 11, 1919, reported that the Lombardy Inn Co. Inc. had filed for bankruptcy, with liabilities of about $68,000 and assets of only $16,000. In January 1920, the fixtures and furnishings of the Lombardy Inn were put up for auction. After thirteen years of business, the Lombardy Inn was no more.

***************

A lengthy and fascinating article was published in the

Boston Evening Transcript, April 13, 1907, and it was titled,

Dining in Little Italy. The article began stating that “

there are the large Italian restaurants—usually on the outskirts of Little Italy—and these are fairly well known to the prosperous ‘bourgeoisie” who like to order a ‘fiasco di Chianti’ and twist maccaroni in ‘The Music Master’ style around their forks,..” However, the article continued, “

But it is the little ‘trattorie’ that are genuine and characteristic of everything Italian.” The article would then describe several of those small "trattorie," some of which were previously described in a Boston Herald article in 1904.

The Trattoria Toscana, on Richmond Street, was described as “... a little, dingy place, with three or four oilcloth-covered tables, a small room at the back where the cooking is done, and a large icechest where butter—good, unsalted Italian butter—and wine are kept cooling.” It was then said, “The floor is sprinkled with sawdust, and around the tables sit Italians of all classes.”

The restaurant was once owned by Bimbo (”baby”) Funai, so called because he was so round, rosy and blond. Bimbo had been an Anarchist, and his restaurant was a meeting place for other malcontents. However, once Bimbo made $8000, he moved back to Tuscany. Then, the cook, Tony, who's also known as Brescia, the name of his native town, became the owner. Tony made “scalpina alla marsala,” which consists of veal, cut very thin, browned with onions, and then stewed with marsala wine. He also made all kinds of maccaroni, with sauces, onions, and garlic. Your dinner here could then end with “caffe nera” (black coffee), gorgonzola or percolino cheese.

The Genoese restaurant on North Street had a bocce alley that ran along the side of the building. The proprietor was Leveroni, who was married to a German woman. The restaurant cookes maccaroni in every fashion and “..the Genoese have an entrancing way of using mushrooms that the other colonies seem not to know.” They also offer risotto, with a thick, delicious sauce of chicken livers, mushrooms and a touch of garlic. An unusual dish is ‘ravioli’ that's consists of calves’ brains, peppers, mushrooms, onions and garlic, all baked in little triangles of pasta. Finally, “..there are salads, salads to dream of, …”

There was a Bolognese trattoria on Cross Street that belonged to Scaroni, which "was picturesque and very Italian.” It came into the hands of Enrico Tassinari, one of the wealthiest Italians in the North End and the restaurant ran under the direction of his son, Johnny Tassinari, and it became more Americanized. In 1905, there was a fire there which killed Tassanari’s pet parrot, which could swear in two languages. Tassanari also owns the farm in Milford which I previously mentioned.

He taught the writer of the article how to cook spaghetti, noting that “you must not break the spaghetti up when you out it on to boil. That makes it ‘bleed,’…and that is the destruction of spaghetti,…” It was also stated, “Next take one and a half pounds of lean beef, brown it carefully in a frying-pan with half a pound of salt pork chopped fine and one large onion. Then put the beef and onions on in a kettle, cover it with water, add half a can of tomatoes, and salt and pepper to taste. Let it slowly simmer until the mixture is a thick dark brownish red; pour it on the spaghetti,..”

There was also a

Sicilian restaurant, owned by

Fratelli Ronca, which had failed and closed. It had also been the only real patisserie that Little Italy ever had and its delicious “

paste cioti” were as good as anywhere. Finally,

Antonio Ciccone was a Neapolitan ‘

confettatore’ who sold ices and cakes in the summer, and candy all year round. for special customers, he might also prepare ‘

lasagne,’ a “

finger-thick maccaroni.”

The article ended, noting, “

…the Italian quarter, where wine is cheap and good, and maccaroni is good and cheap,..” ****************

A new Italian restaurant. The

Boston Journal, October 15, 1907, had an ad for “

Bova’s Italian Restaurant,” which was set to opens on October 18. The owner was

Leo. E. Bova and Co. and the restaurant was located at 96-98 Arch Street, 15-17 Otis Street. The

Boston Herald, October 16, 1907, published the above advertisement, noting it was opening on October 16, two days early. It had a seating capacity of 400, with private booths for small parties and private rooms for larger ones.

A glimpse at their specimen menu. The

Boston Globe, October 17, 1907, published an ad with a specimen menu. Some of the dishes included Spaghetti Napoletana, Rissotto Milanese, Braciolette, Escalloppes Veall alla Genoese, and Escarole.

Business was booming! The

Boston Herald, October 21, 1907, posted a notice that the restaurant was too busy and could not accept booth reservations after 6:30pm.

The

Boston Herald, November 11, 1907, published another ad mentioning that they were so busy that they were now going to open up their men’s café to women too. There would also be a new orchestra on November 11.

The

Boston Herald, June 15, 1908, had an ad which mentioned their new Sala Italiana, Italian room, which will provide more room for their guests with better accommodations and service.

The

Boston Globe, December 17, 1913, published an ad for Cafe Bova, claiming it was "

The Leading Italian Restaurant of Boston." A sample luncheon menu was provided, and the number of Italian dishes was relatively small.

Five years later, Cafe Bova would run into some financial difficulties and it apparently closed in 1918.

***************

Around 1907 or 1908,

Giuseppe Parziale opened a bakery at 78 Prince Street, and it's claimed he first introduced pizza to the New England area. However, none of the newspapers at that time ever mentioned that fact. The

Sunday Telegram, October 30, 1988, noted that the A. Parziale Bakery had a sign in their window proclaiming they were the “

originators of pizza.” The article then continued, “

the story goes that, 100 years ago, the present owner’s grandparents trained most of the bakers in the North End to make our American-style, thin-bottomed pizza.” Later, the

Boston Globe, May 10, 2007, mentioned that A. Parziale & Sons Bakery was started in 1907 by a Neapolitan who first came to New York and then later came to Boston. It was also claimed that in the 1930s, the Parziales served slices of pizza from a push cart in Scollay Square for a nickel. However, that article didn't state they had introduced pizza to Boston.

****************

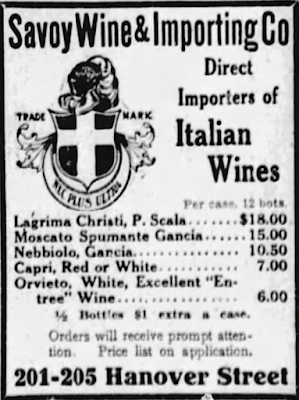

The Boston Globe, March 29, 1908, reported that Antonio G. Tomasello and Frank S. Bacigalupo had applied for a liquor license as Wholesale dealers at 201-205 Hanover as Savoy Wine & Importing Co.

The

Boston Evening Transcript, May 23, 1908, had an ad for Savoy Wine & Importing Co., direct importers of Italian wines, and located at 201-205 Hanover Street. The ad contained some prices per case for Italian wines, varying from $6-$18. The company apparently lasted for another 11 years, when the

Boston Globe, July 14, 1919, reported the Savory Wine partnership was dissolved.

Eight years before, the

Boston Globe, August 30, 1911, reported that

Angelo I. and

Frank S. Bacigalupo, as

Tivoli Wine Co., applied to transfer their liquor license to sell as Victuallers at 858 & 860 Washington St. Then, the

Boston Globe, March 22, 1913, reported they had applied for a liquor license to sell as Victuallers at 858 & 860 Washington St.

A few new restaurants. The

Boston Evening Transcript, October 7, 1908, posted an ad for

Angelo Café, located at 19 Hawley Street. It served lunch and dinner, including "

special Italian dishes."

Back in 1877, there had been an Angelo Cafe at 40 Congress Street, but there was no indication it served Italian dishes. In 1880, the Angelo Cafe moved to 19 Hawley Street, taking over the spot of the former Vossler's. However, there was no mention in the newspapers of the Angelo Cafe for almost 30 years, until 1908. And then in early 1909, the cafe went into bankruptcy and was forced to close.

The spot once occupied by the Angelo Cafe would be taken over by another restaurant. The

Boston Globe, March 26, 1910, reported that

John S. and

Giuditta Dondero applied for a liquor licenses as Victuallers and Wholesale Dealers at 19 & 21 Hawley Street. They would also apply for these licenses in April 1911.

The

Boston Journal, September 26, 1910, published an ad for

Dondero’s, a new French and Italian restaurant, located at 19-21 Hawley Street, which served lunch and dinner.

However, it appears the restaurant closed at the end of 1911, when the building was leased by a different customer.

The Gondola Room, at 181 Hanover Street, in the Hotel Venice, opened on January 12, 1912. The Boston Globe, January 12, 1912, stated that Albert A. Golden opened the new restaurant, "one of the most beautiful Italian dining rooms in the city."

The Hotel Venice, formerly the Ludwig, was apparently opened in 1904, and then sold in 1907, and then sold again in 1908 to Albert A. Golden. It does not appear the Hotel had a restaurant until the Gondola Room opened.

The

Boston Herald, January 27, 1912, had an ad (pictured above) for the

Gondola Room, which they claimed was the “

Finest Italian Restaurant in New England.” The restaurant may only have lasted one more year.

***************

The Boston Globe, August 18, 1912, reported that John B. Piscopo and Allen R. Frederick applied for a liquor license as Victuallers at 195-199 Hanover Street.

An explosion! The Boston Evening Transcript, November 6, 1912, stated that there was a gas explosion at the cafe at 195-199 Hanover St. The cafe floor, made of cement, had been cleaned earlier that day with "gasolene." A lit match dropped on the floor, and ignored the gasolene. The blaze was out by the time the fire department arrived and there were no injuries.

The

Boston Journal, September 20, 1913, published an ad for an Italian Restaurant for Ladies and Gentlemen, located at 195 Hanover at Street and the proprietors were

Piscopo and

Frederick. However, the name of the restaurant is illegible in the newspaper copy. It appears the restaurant might have closed in 1914.

The

Boston Herald, November 23, 1912, had an advertisement for

Café Vesuvius, “

The Newest and finest Italian restaurant in Boston.” It was located at 27-29 Howard Street, and the manager was Felix, who was the former head waiter at the Hotel Napoli. However, the restaurant filed for bankruptcy in 1913.

Robbery! The

Boston Globe, December 21, 1912, briefly noted that there was a robbery at the Italian restaurant of

Angelo Lippi, located at 10 Dix Place in the South End. The

Boston Globe, February 10, 1913, reported that

Angelo Limi, age 36, was arrested at his restaurant for maintaining a nuisance. The police raided the place and found four men playing cards and they also seized four gallons of liquor.

The

Boston Evening Transcript, January 29, 1913, ran an article about restaurants in the North End. to start, the article stated, “

As the largest of the foreign colonies, the Italian Quarter naturally has more restaurants than any other.” However, “

...there is a frequent history of rise, decline and final disappearance. New restaurants spring up every few months.” Unfortunately, many of those restaurants never received any coverage in the local newspapers.

The article continued, “A minestra or an onion soup is apt to be excellent. Peppers are nowhere cooked better than in some of the cheap Italian restaurants of the North End, and one can hardly go astray as to any macaroni on the bill of fare. Kidneys and livers they make into admirable stews, and their spinach or boiled dandelion roots are good and wholesome. Tomatoes, too, they except in preparing for the table.” The article was not fully commentary though. “When it comes to oysters or fish, or the heavier meats, they are not so surely to be trusted, and their fried potatoes are deadly. As to chicken, it is the traditional delicacy of Southern Europe but it seldom pleases the native American diner in cheap Italian restaurants. Tripe, brains and such trifles are made extremely palatable.”

The overall conclusion of the article stated, “In fact the a la carte Italian restaurant serves an astonishingly good and abundant meal for a very small sum.” In addition, “The company may not be elegant, but it is sure to be polite to the stranger.”

The Boston Globe, March 14, 1914, noted that Stephen Fopiano, Corrado Bonugli, and George L. Casale, as Chianti Wine Co., applied for a liquor license as Victuallers at 198-200 Hanover Street. The name of the restaurant wasn't provided. Two years later, in March 1916, they would apply for this license again, but Corrado Bonugli was no longer involved. However, the Boston Post, March 8, 1917, indicated that the partnership had been dissolved and Fopiano had withdrawn from the business. Casale though remained in the business. The Boston Globe, March 24, 1917, indicated that George Casale and Anne Casale applied for a liquor license as Victuallers at 198-200 Hanover Street.

*****************

The Boston Evening Transcript, May 24, 1915, briefly mentioned the Posillipo and Sorrento restaurants in the North End.

The

Boston Herald, November 23, 1920, posted an advertisement for

Posillipo, “

The Only Strictly Italian Restaurant in Boston.” It was located at 145 Richmond Street and the proprietor was

Turcos.

The

Boston Herald, August 19, 1927, had a brief ad for the "

New Posillipo," although it was at the same location. What was new about it?

The

Boston Herald, September 8, 1929, also had a brief ad which mentioned "

Now Open!" as if the restaurant had been closed for some reason.

The

Boston Herald, March 12, 1933, had an ad for Posillipo, which offered "

Famous Italian cuisine."

Maybe the last mention of Posillipo was in the Boston Globe, January 12, 1937, which briefly mentioned it.

*******************

The Boston Globe, August 4, 1917, reported that a woodsman from Maine felt he had been shortchanged at a cafe at 200 Hanover Street. He claimed he gave his waiter a $10 bill but only got change for a $5 bill. The woodsman pulled out a revolver, shot into the air, and struck a chandelier. The other customers fled and the woodsman was arrested by the police.

Another new restaurant. The

Boston Globe, July 3, 1917, had a small ad for the

Blue Grotto, and Italian restaurant located at 292 Hanover Street, which had been remodeled and open for former and new patrons. So, this restaurant had been around since before July 1917, but for an unknown length of time.

The

Sunday Herald, January 11, 1925, had an ad for the Blue Grotto, but used its Italian name, GrottaAzzurra.

*****************

The famed

European Restaurant, located at 218A Hanover Street, allegedly opened in 1917, and would eventually close in 1997, eighty years later. However, this restaurant is illustrative of a matter which applies to a number of other famous Italian restaurants, a number which still exist today. These restaurants received little, if any, publicity in the local newspapers during their early years. They did not advertise in the newspapers, and articles failed to mention their presence. It's possible that these restaurants made little impact in their early years, and it wasn't until years later that they started acquiring their more iconic status.

For example, the first newspaper reference I found for the European Restaurant wasn't until 1921, four years after its opening. And it was a negative mention. The

, the proprietors of a restaurant at 218A Hanover Street. The suit alleged that Walker had gotten sick by eating cabbage which he claimed contained cockroaches. However, the newspapers never reported the outcome of this suit.

There wasn't another mention of the restaurant until 18 years later. The

indicated that New Year celebrators had broken into a couple places seeking alcohol, including the European Restaurant, where they stole about $134 of liquor.

Jump ahead twenty years. The