During this period, the Chinese restaurants attempted to widen their customer base by appealing more to non-Chinese Americans, which would lead to some success. They added more Americanized items to their menus, as well as offering holiday specials, such as for Thanksgiving and New Year's Eve. Nowadays, you don't usually consider dining at a Chinese restaurant for Thanksgiving dinner, especially if you desire a more traditional turkey dinner, but during the early 20th century, it was much more of an option.

The restaurants also often started adding music in the evenings, which, combined with their late hours and the availability of alcohol, made them similar in some ways to night clubs, thus attracting a different clientele. In addition, not all of the Chinese restaurants were located in Chinatown, some having spreading to other areas of Boston.

In some respects, Chinatown gained more respectability during this period, but it also became more violent as well, as two Tongs went to war. This violence would keep some people from journeying to Chinatown, hindering the ability of the restaurant to increase the number of their customers. There were also fears in some circles about the dangers to young women in Chinatown, worries that they would be seduced into opium smoking and prostitution. It was a turbulent time in Chinatown, though ultimately there were positive results.

**********

A gambling raids started off the New Year. The Boston Herald, January 2, 1901, reported that a police officer raided 33A Harrison Avenue, arresting six Chinese for being present where gambling implements were found. In addition, another Chinese was arrested under what appeared to be a new law, where "any person acting as doorkeeper, watchman, or otherwise is equally liable with persons found present." This other Chinese, Jee. S. Toung was alleged to be a watchman.

And them the Boston Herald, January 28, 1901, detailed another gambling raid, which netted the arrest of 25 Chinese at 23 Oxford Street.

It's pleasant to see that one of the first newspaper articles in the 20th century about Chinatown restaurants was especially positive. The Boston Globe, February 10, 1901, published an article with some general information about Chinese businesses from barbers to restaurants. It noted the utter cleanliness of the restaurants, “…the rear of one of the many Chinese restaurants. Everything about the place is neat and clean, as is also the personal attire of the chef. The Chinese are fastidious about the quality of their food, as well as the manner of its preparation.”

There was also reference to some specific Chinese dishes. “These Chinese chefs are especially clever in compounding that curious dish known as “chop sooy,’ a conglomeration of stewed meats and vegetables.” In addition, the article stated, “’Chow mem’ is another choice dish, and an expensive one, too.” It seems likely that “mem” was a typo or misspelling and that the dish was actually “chow mein.” This was the type of article that would entice people to check out Chinese restaurants, a nice alternative to some of the racist articles also found around this time.

The Boston Herald, February 17, 1901, reported that Mayor Hart, and his entourage, including a police escort, went for a tour of Chinatown and the North End one evening. In Chinatown, they visited the Wings at their home on Oxford street, and Mrs. Wing smoked some opium for them. She also told them that she smoked about 50 cents worth of opium each day.

The group also visited the restaurant of the Lock Sen Low Company, at the corner of Harrison and Beach, and later they went to the restaurant of the Hong Far Lo (sic) company. In addition, they visited the headquarters of the Chinese Masonic lodge. There was also a visit to a barber shop, and then the Royal Restaurant. The reason for this tour was not publicly known.

A number of other newspapers during this period would make brief mentions of various Chinese restaurants in Chinatown. For example, there was mention, in March 1901, of a Chinese restaurant, owned by Lock Sen Chin, which was located at the corner of Beach Street and Harrison Avenue.

A number of other newspapers during this period would make brief mentions of various Chinese restaurants in Chinatown. For example, there was mention, in March 1901, of a Chinese restaurant, owned by Lock Sen Chin, which was located at the corner of Beach Street and Harrison Avenue.

More Chinese women coming to Boston. The Boston Herald, March 10, 1901, first noted that Ah Gee was born in Chinatown four years ago to Chinese parents. According to the law, and despite being born in the U.S., Ah Gee cannot be an American citizen. As for Ah Gin, his Chinese father was naturalized as a citizen in 1879, before the first Chinese exclusion law was enacted. And since then, Ah Gin cannot be a U.S. citizen either. The law hasn't been truly contested yet, and there might be loopholes, but so far the judges haven't decided against citizenship. Since 1882, the right of suffrage has been denied to the Chinese. Currently, there are 20 Chinese children, and four of mixed parentage, living in Chinatown.

Some years ago, Chin Fong and Goon Dong, partners in the S.Y. Tank company, brought their Chinese wives over from China. Their eventual children were christened as Methodists. Other Chinese men are planning to bring over their wives as well, especially now that a small group of Chinese wives are already present.

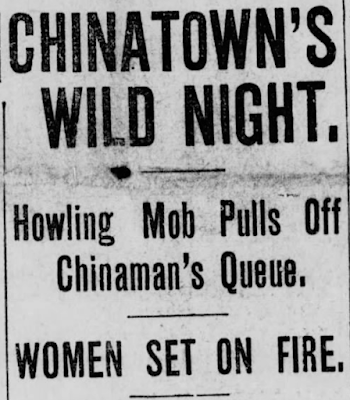

On July 4, 1901, from about 11pm to midnight, a racist mob ran amok in Chinatown. The Boston Post, July 5, 1901, reported on this wild attack. The mob smashed the windows, including large plate glass ones (valued at about $2,000), belonging to Chinese businesses and homes. They also beat any Chinese they found, including going as far as pulling out one man's queue right out of his head. In addition, white women, who tried to pass through the mob, were attacked as well, sometimes pelted with fireworks. Some women' clothing caught fire, although none of the women sustained serious injury.

The mob was estimated at about 3000 men, and the police claimed there was little they could do to stop the violence, describing the mob as "celebrants" of the 4th of July. At around midnight, the police finally regained control and the mob dispersed. Many people in this mob had allegedly been present on Harrison Avenue much earlier that evening, watching the 4th of July celebrations of the Chinese, which included many fireworks. Eventually, the mob turned violent, putting a horrendous ending to the peaceful celebrations.

A Chinese soda fountain! During this time period, soda fountains were extremely popular, especially with young women. According to The Brooklyn Daily Eagle (NY), July 7, 1901, an enterprising Chinese man decided to open a soda fountain in Chinatown, however such businesses could be expensive, especially the more fancy versions. They could easily cost $1,000 to $10,000, which certainly was out of reach for many Chinese businessmen. So, the would-be proprietor sought out just the basics, searching second-hand stores until he found an inexpensive soda foundation, for only $25.

The newspaper stated: “It is a primitive affair and looks much like a silver plated insulated coffee tank that serves good cheer at political rallies and that sort of thing. There is a spigot on each side, and at the base of the tankard of silver there is a circlet of glasses.” He then opened a small job on Harrison Avenue, with a placard in the window, "Ice Cream Soda." Interestingly, he also sold fresh produce, which was also displayed in the window, which he obtained from his own farm in Wakefield.

Ice cream soda was new to most Chinese, and the newspaper noted, "All Chinatown drinking at a soda fountain! It is a sight for the gods to see the Celestials beaming with joy over the foaming soda cups. It is a decided innovation, too, this soda fountain,…” It also printed, “Before an American soda fountain there is always an army of thirsty women waiting to be served, but before the one and only soda fountain in Chinatown none but men congregate,..” There were few women in Chinatown at this time, and most of those that were rarely left their homes, so it's only natural all of the customers were men. Their favorite flavor was apparently lemon, although chocolate was a close second. Unfortunately, I haven't been able to find any additional information about this place. How long did it last?

What is the population of Chinatown? The Boston Herald, August 11, 1901, estimated that about 1200 Chinese lived in Boston, with another 300 in the nearby suburbs. "Boston's Chinatown is very limited in area--indeed, it may be roughly described as bounded by Harrison avenue, Essex, Oxford and Beach streets, two small blocks." On a positive note, the Chinese of Chinatown were said to be, "Here, at least, the yellow man is a frugal, industrious, peace-loving and peace-keeping unit in the social organism ..."

Despite the initial positivity in the first article I mentioned here, fears and concerns about the Chinese continued to manifest themselves. The Boston Post, August 30, 1901, described how hundreds of Chinese were illegally crossing the Canadian border, eventually settling in the Boston area. They were assisted by rich and influential Chinese smugglers, some who lived in Chinatown. The article was concerned that local immigration commissioners were doing little about this matter. Due to the racist Exclusion Act, it was difficult for Chinese to immigrate to the U.S. so some did try to illegally enter the country. However, this influx helped Chinatown grow and the Chinese certainly were hard workers, contributing to the community.

There were some incidents of violence at Chinese restaurants, but they often were caused by white customers starting fights. A Chinese restaurant at 31 Howard Street, owned by King Hong Low, was the scene of multiple problems over the course of a couple years. For example, the Boston Globe, September 7, 1901, reported on a fight that almost became a riot. Some white men started a fight and the other guests “stampeded” out. Unfortunately, two women fainted on the stairs out and were trampled, though there wasn’t any notation that their injuries were serious. One white man and two Chinese men were arrested for assault.

The next month, the Boston Daily Globe, October 31, 1901, reported on another almost riot at this same Chinese restaurant, with the article noting all of the trouble at this place in the recent past. This time, some Italians, who ate at the restaurant, tried to bring their dishes outside and the Chinese insisted they pay for the dishes. The Italians refused and a fight began, with almost fifty people involved in the fracas, wrecking the restaurant and there was plenty of blood spilled. Twenty women hid in a rear room during the battle. In the end, only one Italian and one Chinese man were arrested. An additional person, a bartender at a local saloon, was later arrested for stealing $30 from the restaurant during the riot.

The police explained a main reason for the trouble at this specific location. When the saloons closed at 11pm, people would then gravitate to the Chinese restaurants which were still open. The police also noted the area is frequented by “women of the street” and that the Howard Street gangs were also known to dine there.

Despite the initial positivity in the first article I mentioned here, fears and concerns about the Chinese continued to manifest themselves. The Boston Post, August 30, 1901, described how hundreds of Chinese were illegally crossing the Canadian border, eventually settling in the Boston area. They were assisted by rich and influential Chinese smugglers, some who lived in Chinatown. The article was concerned that local immigration commissioners were doing little about this matter. Due to the racist Exclusion Act, it was difficult for Chinese to immigrate to the U.S. so some did try to illegally enter the country. However, this influx helped Chinatown grow and the Chinese certainly were hard workers, contributing to the community.

There were some incidents of violence at Chinese restaurants, but they often were caused by white customers starting fights. A Chinese restaurant at 31 Howard Street, owned by King Hong Low, was the scene of multiple problems over the course of a couple years. For example, the Boston Globe, September 7, 1901, reported on a fight that almost became a riot. Some white men started a fight and the other guests “stampeded” out. Unfortunately, two women fainted on the stairs out and were trampled, though there wasn’t any notation that their injuries were serious. One white man and two Chinese men were arrested for assault.

The next month, the Boston Daily Globe, October 31, 1901, reported on another almost riot at this same Chinese restaurant, with the article noting all of the trouble at this place in the recent past. This time, some Italians, who ate at the restaurant, tried to bring their dishes outside and the Chinese insisted they pay for the dishes. The Italians refused and a fight began, with almost fifty people involved in the fracas, wrecking the restaurant and there was plenty of blood spilled. Twenty women hid in a rear room during the battle. In the end, only one Italian and one Chinese man were arrested. An additional person, a bartender at a local saloon, was later arrested for stealing $30 from the restaurant during the riot.

The police explained a main reason for the trouble at this specific location. When the saloons closed at 11pm, people would then gravitate to the Chinese restaurants which were still open. The police also noted the area is frequented by “women of the street” and that the Howard Street gangs were also known to dine there.

No Christmas in Chinatown. The Boston Herald, December 26, 1901, examined Christmas observances in Chinatown. The writer found one Chinese man who stated there is no Christmas in Chinatown, and that they save their money for the celebration of Chines New Year. The article stated, "Christmas day has no sentimental attachment for Chinamen in general." The larger merchant stores observe the Christmas season, trying to appeal to shoppers. Christmas day also became a day of rest for many Chinese, who closed their shops around noon. A few of the restaurants offered a Christmas dinner, offering turkey meals.

Moy Loy, the "king of Chinatown," who lives at 26 Stratford Street, Dorchester, celebrates Christmas at his home with his family, his wife and two children. And he took has a turkey dinner for Christmas day. Moy is allegedly the wealthiest Chinese man in Boston, working as an interpreter for the government. He is also the largest importer of Chinese goods.

The Chinese Exclusion Act was invoked. The Boston Globe, January 21, 1902, reported that Yee Lop Jung had been arrested, in a laundry on Columbus Avenue, on the charge of being unlawfully in the country, a violation of the Chinese Exclusion Act. As a follow-up, the Boston Globe, May 20, 1902, stated that U.S. Commissioner Fiske had ordered Yee Lop Jung to be deported. The article also noted, “A peculiar phase of the case was the absence of any Chinese sympathizers when the case was called. It is generally the custom when a fellow-countryman is in the tolls to have the corridors fairly swarm with yellow-skinned sympathizers, but this morning there was no evidence of sympathizing Chinamen in the hallways.” Why was this the case? Well, the article also noted, “The Chinamen accuse Lop of extorting money from them by threats, saying that he would ‘peach’ on their little card sessions and gambling parties.”

As reported in the Boston Evening Transcript, June 28, 1902, “He is the first Chinaman to be ordered deported by the United States District Court for Massachusetts under the Chinese exclusion law.” That's interesting as the Chinese Exclusion Act had been in operation for 20 years, and this was the first deportation in Massachusetts. If the Chinese had stood up for Yee Lop Jung, then maybe he wouldn't have been deported either. As for his thoughts on Chinatown, he stated, "Chinatown has changed much."

The Boston Post, June 29, 1902, provided more information in this regard. “It has always been the easiest possible thing for a Chinamen arrested on the charge of violating the exclusion act to summon his friends, who would swear by all the Chinese gods that the arrested man had long been a resident of the United States. Though he came direct from China willing people would testify that they knew him well when he was in American before.” Unfortunately for Yee Lop Jung, no one would step forward to vouch for him or help with his bail. It was alleged that he was an informant for the police, informing them on illegal gambling in Chinatown. His wife was even threatened due to his alleged snitching.

Trouble at Hong Far Low. The Boston Herald, August 9, 1902, reported that Carl Dinmick, of 77 Tyler Street, was arrested for drunkenness. He visited Hong Far Low, at 37 Harrison Avenue, where they demanded he pay for his chop suey up front. Carl got angry and physical, ending up at the bottom of the stairs of the building, holding a revolver. The police found him there and took him into custody.

In December 1902, there was a new Chinese restaurant, Hawm Fah Low & Co., located at 777 Washington Street, and serving Chop Sooey and other dishes.

Tong violence didn't arrive until the new year. The Boston Herald, January 25, 1905, reported that last night, there had been a shooting in Chinatown. Lem Wong Goon, husband of Nellie Wong Goon and a member of the On Leong, owned a grocery in the basement of the rear of 23 Oxford Street. Two Chinese burst into the store and opened fire, with at least 9 shots fired, but fortunately only one bullet struck Lem, hitting him in the left leg. The police sought Yee Yoey and Joe Guey, Hep Sing members, as the alleged shooters.

Later that day, The Boston Globe, January 25, 1905, indicated the police arrested Yee Yuee, aged 29, of 86 Dartmouth Street, for assault and battery with attempt to kill Lem. They were still seeking the second shooter. A later edition of this newspaper added that the shooters used 41 caliber guns; and that Lem's wife, Nellie, was said to be “the prettiest white girl in Chinatown.” Joe Guey was arrested the next day.

The Boston Post, January 27, 1905 reported that the police raided the Hep Sing headquarters and found four men, thought to be Highbinders from New York. The police shipped them back to New York, fearing they were in Boston to kill members of the On Leong. More fears were revealed in the Boston Herald, August 7, 1905, with rumors of out-of-town assassins coming to Chinatown, and tong members walking around in chain mail shirts, wielding weapons. These rumors, of out-of-town assassins coming to Boston, were frequent during this time period, and commonly didn't result in any actual violence. There was plenty of fear but not all seemed justified.

Tong war fears continued. The Boston Daily Globe, August 26, 1905, noted that recent tong killings in New York, by the On Leong against the Hep Sing, might spur on revenge in Boston. The local On Leong also had some internal problems as the Chin family, about 50-60 people, left the On Leong Tong, claiming the assessment of fees to pay for court costs and gambling fines were too high. This weakened the tong, making them vulnerable and a more enticing target to the Hep Sing. The article also mentioned, “Sunday is the day when the laundrymen from all the suburbs and outlying towns and cities come in to Boston, ostensibly to buy Chinese groceries, but principally, the police say, to gamble,..”

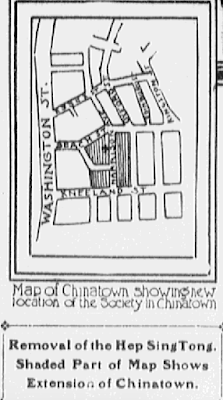

The Boston Sunday Globe, August 27, 1905, provided a photo of the Chinese bulletin board located on Oxford place in Chinatown. The board, about fifteen feet long and five feet wide, was located on the dead wall on the northerly side of the alley. Though anyone in Chinatown could post bulletins here, the tongs did so too, posting bulletins on flaming red paper with black letters. And the Boston Daily Globe, August 30, 1905, noted that a new notice on the board told the Chins to pay their dues and assessments and come back to the tong or face the wrath of the On Leongs.

The Chins weren't finding sanctuary with the Hep Sings. The Boston Daily Globe, September 11, 1905, claimed that the police learned that Chin and Moy factions of the On Leong, and the Hep Sing have all been stockpiling weapons, primarily revolvers and hatchets. The Hep Sing refused to accept the Chins into their tong. The police increased their presence in Chinatown, trying to determine where the arsenals were being stored. The Boston Post, September 11, 1905, reported that the police chose to make two raids, at 23 Oxford Street and 13 1/2 Harrison Avenue. At Oxford, they arrested ten Hep Sing members and at Harrison, they arrested 12 members of the On Leong. These raids were though to have prevented tong violence.

The above advertisement is from the Boston Globe, September 24, 1905, noting the Shanghai Low, a “first-class Chinese restaurant” located at 42 ½ Harrison Avenue.

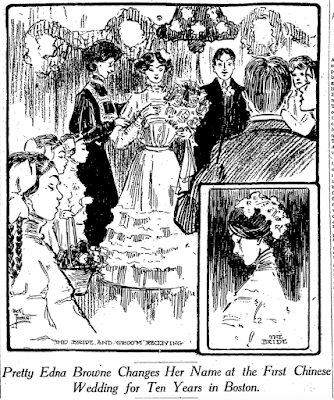

The Boston Herald, January 8, 1907, discussed the wedding of King and Browne, said to be the first wedding in Boston in 10 years of two Chinese. The wedding was a major event in Chinatown, and the article describes everything as almost a fairy tale.

**********

The usual Chinatown gambling raids. The Boston Morning Journal, January 6, 1902, noted that another Sunday gambling raid was made, which was a regular occurrence, There were actual two raids made, both on Oxford place, and 11 Chinese were arrested, with the seizure of fan-tan and lottery paraphernalia.

The Chinese Exclusion Act was invoked. The Boston Globe, January 21, 1902, reported that Yee Lop Jung had been arrested, in a laundry on Columbus Avenue, on the charge of being unlawfully in the country, a violation of the Chinese Exclusion Act. As a follow-up, the Boston Globe, May 20, 1902, stated that U.S. Commissioner Fiske had ordered Yee Lop Jung to be deported. The article also noted, “A peculiar phase of the case was the absence of any Chinese sympathizers when the case was called. It is generally the custom when a fellow-countryman is in the tolls to have the corridors fairly swarm with yellow-skinned sympathizers, but this morning there was no evidence of sympathizing Chinamen in the hallways.” Why was this the case? Well, the article also noted, “The Chinamen accuse Lop of extorting money from them by threats, saying that he would ‘peach’ on their little card sessions and gambling parties.”

The Boston Post, January 24, 1902, related the story of how an assistant constable from Chelsea, entered the Howard Street restaurant, claiming to actually be the Chief of the Chelsea police. He nearly caused another riot, as he complained about the food, the actions of the employees, and even insulted the appearance of the Chinese. He angered the Chinese who demanded to see his authority, and it was at that point that he finally backed down. He fled from the restaurant, and eluded capture by the police.

In 1902, there were a couple intriguing articles about Chinese New Year. First, the Boston Evening Transcript (MA), February 6, 1902, wrote about the New Year celebrations, with some emphasis on food, praising Chinese chefs. As it stated, “The Chinese cook is an artist, who observes the requirements of human digestion as well as the possibilities of spices, and knows that simplicity is the highest form of art. That is—the board does not groan beneath a great burden of undigestible dishes, but the few that are chosen are choice and cooked to perfection.”

Specifically, “A dish that is sure to bring satisfaction is Chow Mein.” The article continued, “This is the manner of its making. First, noodle paste is shredded into long jackstraw looking strips, and piled up on a platter like a haymoy. Then boneless chicken, chopped celery and olives are cooked over a lively fire in olive oil, and when done to a brown the whole is pored over the haymoy. When served with green gage plums and a pot of fresh tea—well, it is a revelation of what is good in the way of things to eat.”

There was also mention of some other dishes including Chow Gui Pan (fried boneless chicken) and for dessert, Boo Low (pineapple), Sar Lee (preserved pears), and Tongaung (preserved ginger).

In 1902, there were a couple intriguing articles about Chinese New Year. First, the Boston Evening Transcript (MA), February 6, 1902, wrote about the New Year celebrations, with some emphasis on food, praising Chinese chefs. As it stated, “The Chinese cook is an artist, who observes the requirements of human digestion as well as the possibilities of spices, and knows that simplicity is the highest form of art. That is—the board does not groan beneath a great burden of undigestible dishes, but the few that are chosen are choice and cooked to perfection.”

Specifically, “A dish that is sure to bring satisfaction is Chow Mein.” The article continued, “This is the manner of its making. First, noodle paste is shredded into long jackstraw looking strips, and piled up on a platter like a haymoy. Then boneless chicken, chopped celery and olives are cooked over a lively fire in olive oil, and when done to a brown the whole is pored over the haymoy. When served with green gage plums and a pot of fresh tea—well, it is a revelation of what is good in the way of things to eat.”

There was also mention of some other dishes including Chow Gui Pan (fried boneless chicken) and for dessert, Boo Low (pineapple), Sar Lee (preserved pears), and Tongaung (preserved ginger).

The Boston Herald, February 8, 1902, discussed the issue of Chinese immigration and the recent speech by Reverend Dr. Wendte. The article stated that Wendte was exaggerating the dangers of such immigration. In the last fiscal year, about 488,000 immigrants entered the U.S. and only 2459 of them were Chinese, quite a small percentage. Since 1885, there hasn't been a year when the number of Chinese immigrants reached 3500. In some years, the number was even less than 100. The article noted that "...the fears expressed are those of prejudiced ignorant rather than reason." During the last fiscal year, about 136,000 Italian immigrants came to the U.S,, many who wanted to earn money here and then return home, the same allegation made against the Chinese.

The Boston Post, February 10, 1902, noted that “The celebration of New Year’s week in Chinatown this year is one of the most quiet in the history of that part of Boston. The reason for this is the recent arrest and trial of so many of the Chinamen for not having proper papers of admission to the country. In some cases where the papers have been all right the trials have cost the Chinamen as much as $200.” The article also printed a copy of a New Year 's dinner menu, pictured above. Quite a feast!

The Boston Post, February 10, 1902, noted that “The celebration of New Year’s week in Chinatown this year is one of the most quiet in the history of that part of Boston. The reason for this is the recent arrest and trial of so many of the Chinamen for not having proper papers of admission to the country. In some cases where the papers have been all right the trials have cost the Chinamen as much as $200.” The article also printed a copy of a New Year 's dinner menu, pictured above. Quite a feast!

The Boston Morning Journal, March 20, 1902, detailed information from former police officer George A. Jordan, who had been a top cop in Chinatown for years. Interestingly, the officer was now in the laundry business, although he had only been working in the business for a week. s for his thoughts on Chinatown, he stated, "Chinatown has changed much."

He added that Chinatown now had about 30 white women who had married Chinese men, living on Oxford street and Oxford place. About a dozen Chinese women live with their husbands on Harrison, as well as one white wife, the infamous Belle, the Queen of Chinatown. Four or five Chinese children attended the Quincy School.

In addition, he mentioned that many squeal on each other about gambling, especially those who lose. However, he also states that it's impossible to stop them from gambling, as they haven't stopped at all despite years of constant police raids. He also said, "As a whole they are very peaceable." Plus, he mentioned that only doing Chinese men are in prison, having engaged in robbery.

The Boston Morning Journal, May 19, 1902, briefly noted that the three young daughters, close to 6 years old, of Goon Dong, attend the kindergarten in Barnard Memorial on Warrenton Street. They dress in American frocks and bonnets.

The mystery of a dead Chinese in the river. The Boston Herald, June 4, 1902, reported that yesterday the body of a Chinese man was found dead in the Charles River, near the Boston & Maine drawbridge. Currently, it's unknown whether this was an accident, suicide or murder. It's thought he was a laundryman, maybe about 25-30 years old. The police allege this could have been a murder by a secret Chinese society, although there is no proof of such. The police have been in Chinatown, trying to determine the identity of the deceased.

The mystery was quickly resolve as noted in the Boston Herald, June 6, 1902. The deceased was Yee Hung Tang, who committed suicide. He was well known in Chinatown and nicknamed the "Professor" because of his superior education. "Relatives say that his mind had been weakened by over-application to his studies."

As reported in the Boston Evening Transcript, June 28, 1902, “He is the first Chinaman to be ordered deported by the United States District Court for Massachusetts under the Chinese exclusion law.” That's interesting as the Chinese Exclusion Act had been in operation for 20 years, and this was the first deportation in Massachusetts. If the Chinese had stood up for Yee Lop Jung, then maybe he wouldn't have been deported either. As for his thoughts on Chinatown, he stated, "Chinatown has changed much."

The Boston Post, June 29, 1902, provided more information in this regard. “It has always been the easiest possible thing for a Chinamen arrested on the charge of violating the exclusion act to summon his friends, who would swear by all the Chinese gods that the arrested man had long been a resident of the United States. Though he came direct from China willing people would testify that they knew him well when he was in American before.” Unfortunately for Yee Lop Jung, no one would step forward to vouch for him or help with his bail. It was alleged that he was an informant for the police, informing them on illegal gambling in Chinatown. His wife was even threatened due to his alleged snitching.

The Boston Herald, July 2, 1902, reported more on gambling raids. During the previous week or so, on four separate days, the police made 6 raids in Chinatown and over 20 Chinese men were arrested, along with the seizure of a bunch of gambling implements. However, during none of these raids, did the police find anyone actually gambling. The police alleged the reason for this is due to a gambling syndicate that is playing a game with the police.

Allegedly, the ring informs the police of a game in operation, but another member of the ring tells the men at the game that the police are coming, although the notification only gives the Chinese sufficient time to stop playing, but not to flee the premises. And the man who warns the gamblers gets money for warning them of the police.

The Boston Herald, July 8, 1902, noted that there was a "certain fat white man," from the West End, who was behind the policy lottery in Chinatown, who simply takes a cut of the money, doing nothing for it. Previously, the police had driven all of the white men, who promoted a policy lottery, out of Chinatown, most resettling in the West End. However, the police are after this person, and refuse to take his bribes, and recently raided his Chinese friends at 10 Oxford Place.

They arrested Gee Yee Lee, this white man's main Chinatown contact, and seized lots of policy lottery slips and sheets. He was quickly bailed out by agents of the white man, although curiously this white man wasn't named in this article.

Police abuse of the Chinese. The Boston Herald, July 16, 1902, reported on allegations of police abuse against Chinese who were the subject of gambling arrests. Lawyer Thomas J. Barry has been retained by some prominent Chinese businessmen and he told the newspaper, "Police abuse of Chinamen taken in gambling raids in this city must stop." He added that police have been "treating Chinamen worse than cattle of late."

The Chinese allege that in recent gambling arrests, the police have assaulted some of them too, usually with clubs, where two had to seek medical attention for their injuries. There are also deeper allegations of police corruption, taking bribes from the Chinese, and it's said that the heavy handed clubbing might be partially conducted to gain more information on who is providing those bribes and to whom.

He would finally be deported in July. The Boston Globe, July 29, 1902, noted that he was taken on an early afternoon train for Providence, Rhode Island, where he would be joined with other Chinese who were being deported. They would then sail from Providence by steamer for Norfolk; where they would next take a train to San Francisco, by way of New Orleans and the Santa Fe route.

Trouble at Hong Far Low. The Boston Herald, August 9, 1902, reported that Carl Dinmick, of 77 Tyler Street, was arrested for drunkenness. He visited Hong Far Low, at 37 Harrison Avenue, where they demanded he pay for his chop suey up front. Carl got angry and physical, ending up at the bottom of the stairs of the building, holding a revolver. The police found him there and took him into custody.

Another gambling raid, discovering a huge stake. The Boston Herald, August 18, 1902, detailed another police raid in Chinatown at 23 Harrison Avenue, finding a fan-tan game. Thirteen Chinese were arrested and $500 was found on the table, which was split up among the Chinese and not claimed by the police. One of the Chinese stated that was one of the largest fan-tan pots ever seen in Boston.

A christening of a Chinese boy. The Boston Herald, August 20, 1902, discussed the large festivities for the christening of the son, named Chong Goon, of Wong Go Chee, who lives at 3 Oxford Place. It was a major event all across Chinatown, and the boy received many valuable presents. At a restaurant at 15 Harrison Avenue, there was a huge feast, of about ten courses, with many rare dishes.

Fan-tan raids once again. The Boston Herald, August 25, 1902, stated there had been two police raids yesterday. The first was at 5 Oxford Place and 23 Chinese were arrested, while the second raid was at 42 1/2 Harrison Avenue, where the police entered through a skylight, and 28 Chinese were arrested.

As there still were so few Chinese women in Chinatown, and those who existed were married, a number of Chinese men married American woman. Domestic life wasn’t always blissful. The Boston Post, August 27, 1902, interviewed Mrs. Loo Sun, the American wife of a Chinese tailor at 27 Harrison Avenue about her recent domestic abuse. Her husband had choked her, and was later arrested, convicted for assault and fined $10. Mrs. Loo Sun planned on leaving her husband and had some derogatory comments about Chinatown, stating, “A girl had better be shot before she ever comes to live down here...There are about 30 white girls in this vicinity living with Chinese husbands and we are all sick and tired of the life.”

As there still were so few Chinese women in Chinatown, and those who existed were married, a number of Chinese men married American woman. Domestic life wasn’t always blissful. The Boston Post, August 27, 1902, interviewed Mrs. Loo Sun, the American wife of a Chinese tailor at 27 Harrison Avenue about her recent domestic abuse. Her husband had choked her, and was later arrested, convicted for assault and fined $10. Mrs. Loo Sun planned on leaving her husband and had some derogatory comments about Chinatown, stating, “A girl had better be shot before she ever comes to live down here...There are about 30 white girls in this vicinity living with Chinese husbands and we are all sick and tired of the life.”

Crime statistics. The Boston Herald, October 2, 1902, detailed some of the crime statistics for Boston for the year that ended on September 30. Gambling arrests were up, thought to be largely because of the constant raids in Chinatown. There were 345 warrants for gaming apparatus but only 97 were seized. There were also 3 warrants for opium, with 3 seizures.

In December 1902, there was a new Chinese restaurant, Hawm Fah Low & Co., located at 777 Washington Street, and serving Chop Sooey and other dishes.

Christmas observances rare in Chinatown once again. The Boston Herald, December 26, 1902, noted that, "Five little children out of the entire population in Chinatown were the only ones to celebrate Christmas." The children, aged 5-8 years old, went to the Christmas tree celebration at the Harvard Street Baptist Church. In Chinatown, Christmas Day is simply seen as similar to an extra Sunday to them. Once again it was noted that the Chinese have their major celebration for Chinese New Year's.

The Boston Herald, February 26, 1903, reported that Norman Spring, a railroad yardmaster, and a friend, named Tripp, dined at a Chinese restaurant on Harrison Avenue in Chinatown. They ordered chop suey and Tripp didn't like it. The waiter, Chin Toy, asked for them to pay their check and they stated they would do so when they were "good and ready to settle." There was a disagreement over what happened next, the waiter alleging Spring threw a valuable vase at him, while Spring and Tripp claimed the waiter was the aggressor. Spring ended up with a broken arm. At court, the judge imposed a $25 fine on the waiter, believing Spring and Tripp had some responsibility, and the waiter appealed the decision.

New Tongs were being established in Chinatown, and war would soon thereafter result. I previously wrote about the Hop Dock Tong, which was founded around 1890. As I stated, Tongs were secret, sworn Chinese brotherhoods which were claimed to have been formed for a variety of social or business purposes but often engaged in criminal activities. The Chinese term for "tong" literally means "chamber," and can actually be used to refer to many different organizations, including many without any connection to criminal activity. The Hop Dock Tong seemed to vanish and I didn't find any additional references to it in the 20th century.

The Boston Sunday Post, March 8, 1903, wrote about the formation of the Hep Sing Tong, the Chinese Mutual Protective Society, which celebrated three days of festivities, including "waking" Quong Gong, a Chinese God, at a temple on the third floor of a building on Beach Street. The ceremony was conducted by Muck Duck of New York City.

Additional information was provided in the Boston Post, March 10, 1903, noting that Quong Gong, was the patron god of the Hep Sing Tong. Wong Aloy, a Chinese interpreter in the New York City court system was quoted, “What is the object of the society? It is not for secrets, but for self-protection. The members pay dues enough to keep the rent paid. Brothers and good friends, when the time of trouble and need comes, the right of justice comes, our new society, now having a branch in Boston and every city in the U.S., goes to the aid of its members.” Wong also stated, “Most of the men who make the trouble are gamblers and scoundrels. They take the money from these boys who have to work so hard in laundries—men who are their own brothers.”

All of that sounded great but was it actually the truth? Five months after its formation, violence was associated with the Tong. The Boston Sunday Post, August 16, 1903, detailed how Moy Yen was arrested the previous night, charged with assault and battery, with a loaded revolver, on Lew Toy and Yee Yah at 48 Beach Street. Allegedly, the two victims, both members of the Hep Sing, were chosen to be killed because they were providing information to the police on gambling in Chinatown. The article also noted a number of other recent assaults in Chinatown. Internal problems, which were being resolved with bullets.

Another Tong then was founded in Chinatown, directly opposed to the Hep Sing. The Boston Daily Globe, September 1, 1903, mentioned the formation of the On Leung Tong, which would be headquartered at 35 Harrison Avenue and start with 60-70 members. There was more information in the Boston Daily Globe, September 3, 1903. The On Leong Tong, also known as the Chinese Merchants Association, would be located on the 3rd and 4th floors at 35 Harrison Avenue, and its membership included Chinese merchants located in Rhode Island too. Wing Ling Ark was appointed as the acting president until elections could be held. There was also a note that this Tong had flourished in San Francisco, New York City and Chicago. Their banquet was held at the Lock Sen Low restaurant at 46 Beach Street.

In a letter to the editor in the Boston Daily Globe, September 8, 1903, an H.S. Lee claimed that the On Leong Tong was an “organization of Chinese gamblers banded together for protection and profit,…” However, in the Boston Post, September 9, 1903, the police denied those rumors stating they would know if a large scale gambling club existed in Chinatown.

Both the Hep Sing and On Leong Tongs originated in San Francisco, and eventually spread to other enclaves of the Chinese in other cities. The Hep Sing, whose name translates as the “Chamber United in Victory,” emerged in the mid-1880s. Around the same time, the On Leong Tong, whose name translates roughly as “Chamber of Peaceful Conscientiousness,” was established around this time as well. They became competitors, which eventually led to murder in August 1900 in New York City, initiating the First Tong War, which lasted for about six years. Tong problems in New York would spread to other cities, including Boston, where those tongs were also located. The emergence of these two Tongs in Boston, as a Tong War raged in New York City, didn't bode well for Chinatown.

A fascinating, and positive, article on Chinatown appeared in The New England Magazine (March to August 1903, v.28), in an article titled China in New England written by Herbert Heywood. The article stated, “You may have had some lurking impression before that the Chinese quarter was a blot upon the city, now you know that it contains men as highly cultivated, as sensitive to all the amenities of life as the blue blooded Puritans that live at the other end of the town. It is just a difference of color, place of birth and surroundings.” In addition, it described Chinatown, “Here, with the recently widened streets, there is little to show that you are in the Celestial quarter, except the fantastic signs and balconies of a few restaurants and the displays of teas and china in the store windows, and a thin sprinkling of Chinamen on the sidewalks and in the doorways.”

There is then some discussion of the restaurants in Chinatown, noting that there are currently only about six. “Of the restaurants there are about half a dozen, fitted up in gorgeous Oriental style—” and “Each of these restaurants has its own particular class of patrons. To one comes the sporting element at night from the theatres and neighboring saloons and makes merry as late as the law will allow. Another aspires to a better class of patronage and is kept by Christians and members of a Christian Endeavor Society.”

Plus, the article mentioned, “Sunday afternoon is the time when they congregate in Chinatown to visit friends and buy their tea, liche nuts, dried mushrooms, rice and the other eatables and articles of dress imported by the Oriental merchants. Finally, they provided information about the low number of Chinese women in the city. “But as there are only fifteen Chinese women in all Boston, and these the wives of merchants.”

The Boston Herald, March 31, 1903, stated that a riotous assault occurred at a Chinese restaurant on Howard Street. Several sailors dined at the restaurant, caused some trouble, and were evicted. The next day, a big sailor went to the restaurant, smashed the glass out of the doorway and viciously assaulted a waiter, who needed medical attention. The police were seeking the sailor.

The Boston Herald, February 26, 1903, reported that Norman Spring, a railroad yardmaster, and a friend, named Tripp, dined at a Chinese restaurant on Harrison Avenue in Chinatown. They ordered chop suey and Tripp didn't like it. The waiter, Chin Toy, asked for them to pay their check and they stated they would do so when they were "good and ready to settle." There was a disagreement over what happened next, the waiter alleging Spring threw a valuable vase at him, while Spring and Tripp claimed the waiter was the aggressor. Spring ended up with a broken arm. At court, the judge imposed a $25 fine on the waiter, believing Spring and Tripp had some responsibility, and the waiter appealed the decision.

New Tongs were being established in Chinatown, and war would soon thereafter result. I previously wrote about the Hop Dock Tong, which was founded around 1890. As I stated, Tongs were secret, sworn Chinese brotherhoods which were claimed to have been formed for a variety of social or business purposes but often engaged in criminal activities. The Chinese term for "tong" literally means "chamber," and can actually be used to refer to many different organizations, including many without any connection to criminal activity. The Hop Dock Tong seemed to vanish and I didn't find any additional references to it in the 20th century.

The Boston Sunday Post, March 8, 1903, wrote about the formation of the Hep Sing Tong, the Chinese Mutual Protective Society, which celebrated three days of festivities, including "waking" Quong Gong, a Chinese God, at a temple on the third floor of a building on Beach Street. The ceremony was conducted by Muck Duck of New York City.

Additional information was provided in the Boston Post, March 10, 1903, noting that Quong Gong, was the patron god of the Hep Sing Tong. Wong Aloy, a Chinese interpreter in the New York City court system was quoted, “What is the object of the society? It is not for secrets, but for self-protection. The members pay dues enough to keep the rent paid. Brothers and good friends, when the time of trouble and need comes, the right of justice comes, our new society, now having a branch in Boston and every city in the U.S., goes to the aid of its members.” Wong also stated, “Most of the men who make the trouble are gamblers and scoundrels. They take the money from these boys who have to work so hard in laundries—men who are their own brothers.”

All of that sounded great but was it actually the truth? Five months after its formation, violence was associated with the Tong. The Boston Sunday Post, August 16, 1903, detailed how Moy Yen was arrested the previous night, charged with assault and battery, with a loaded revolver, on Lew Toy and Yee Yah at 48 Beach Street. Allegedly, the two victims, both members of the Hep Sing, were chosen to be killed because they were providing information to the police on gambling in Chinatown. The article also noted a number of other recent assaults in Chinatown. Internal problems, which were being resolved with bullets.

Another Tong then was founded in Chinatown, directly opposed to the Hep Sing. The Boston Daily Globe, September 1, 1903, mentioned the formation of the On Leung Tong, which would be headquartered at 35 Harrison Avenue and start with 60-70 members. There was more information in the Boston Daily Globe, September 3, 1903. The On Leong Tong, also known as the Chinese Merchants Association, would be located on the 3rd and 4th floors at 35 Harrison Avenue, and its membership included Chinese merchants located in Rhode Island too. Wing Ling Ark was appointed as the acting president until elections could be held. There was also a note that this Tong had flourished in San Francisco, New York City and Chicago. Their banquet was held at the Lock Sen Low restaurant at 46 Beach Street.

In a letter to the editor in the Boston Daily Globe, September 8, 1903, an H.S. Lee claimed that the On Leong Tong was an “organization of Chinese gamblers banded together for protection and profit,…” However, in the Boston Post, September 9, 1903, the police denied those rumors stating they would know if a large scale gambling club existed in Chinatown.

Both the Hep Sing and On Leong Tongs originated in San Francisco, and eventually spread to other enclaves of the Chinese in other cities. The Hep Sing, whose name translates as the “Chamber United in Victory,” emerged in the mid-1880s. Around the same time, the On Leong Tong, whose name translates roughly as “Chamber of Peaceful Conscientiousness,” was established around this time as well. They became competitors, which eventually led to murder in August 1900 in New York City, initiating the First Tong War, which lasted for about six years. Tong problems in New York would spread to other cities, including Boston, where those tongs were also located. The emergence of these two Tongs in Boston, as a Tong War raged in New York City, didn't bode well for Chinatown.

A fascinating, and positive, article on Chinatown appeared in The New England Magazine (March to August 1903, v.28), in an article titled China in New England written by Herbert Heywood. The article stated, “You may have had some lurking impression before that the Chinese quarter was a blot upon the city, now you know that it contains men as highly cultivated, as sensitive to all the amenities of life as the blue blooded Puritans that live at the other end of the town. It is just a difference of color, place of birth and surroundings.” In addition, it described Chinatown, “Here, with the recently widened streets, there is little to show that you are in the Celestial quarter, except the fantastic signs and balconies of a few restaurants and the displays of teas and china in the store windows, and a thin sprinkling of Chinamen on the sidewalks and in the doorways.”

There is then some discussion of the restaurants in Chinatown, noting that there are currently only about six. “Of the restaurants there are about half a dozen, fitted up in gorgeous Oriental style—” and “Each of these restaurants has its own particular class of patrons. To one comes the sporting element at night from the theatres and neighboring saloons and makes merry as late as the law will allow. Another aspires to a better class of patronage and is kept by Christians and members of a Christian Endeavor Society.”

Plus, the article mentioned, “Sunday afternoon is the time when they congregate in Chinatown to visit friends and buy their tea, liche nuts, dried mushrooms, rice and the other eatables and articles of dress imported by the Oriental merchants. Finally, they provided information about the low number of Chinese women in the city. “But as there are only fifteen Chinese women in all Boston, and these the wives of merchants.”

The Boston Herald, March 31, 1903, stated that a riotous assault occurred at a Chinese restaurant on Howard Street. Several sailors dined at the restaurant, caused some trouble, and were evicted. The next day, a big sailor went to the restaurant, smashed the glass out of the doorway and viciously assaulted a waiter, who needed medical attention. The police were seeking the sailor.

The Boston Herald, May 12, 1903, reported on the allegation that "Chinese Harry" ran an opium joint. Harry Leslie, 29 years old, who lives in Cambridge is well known as a guide to Chinatown. Two days ago, while making their rounds, the police stopped at 22 Oxford Street and found a small room on the top floor which was an opium joint. The police found three young white men, and two young white women, smoking opium and it was alleged Harry ran the place. As the police lacked a warrant, they simply noted the names of those present and then left.

However, the Boston Journal, May 12, 1903, noted that Harry was arrested yesterday by the police. The Boston Herald, May 13, 1903, then added that Harry was fined $75 for keeping an opium joint, but he appealed.

It would also be during the first two decades of this century that "slumming parties" in the Boston area started to become popular. This was said to be a trend that started in London in the 19th century, and traveled to New York around 1884. In essence, well-off people went to poorer neighborhoods, such as Chinatown, as voyeurs, to experience what they perceived as the "seedier" areas. They wanted to temporarily live on the edge, to rub elbows with criminals and drug users, but with the ability to go back to their comfy homes afterwards. Eventually, there would even be tour guides offering slumming trips to various neighborhoods, including Chinatown.

Slumming Parties prohibited! The Boston Journal, June 28, 1903, ran an article titled, "Slumming Parties In Chinatown Forbidden By Police." The article stated, "Like all other large cities, Boston has its Chinatown. It lies in the vicinity of Harrison avenue and Oxford street, and through the by-ways and alleys which lead off from those and other contiguous thoroughfares at the most unexpected angles." In a positive spin, the article continued, "Just now, however, it's a very good little Chinatown...No more fan tan. No more pipe dreams." This meant that gambling and opium smoking had largely vanished. And as a direct result of Chinatown becoming more respectable, it had become "boring" in some circles, and "slumming parties" were less frequent. In addition, slumming parties had been semi-legally prohibited, though tough to enforce.

In addition, despite these police claims that gambling and opium smoking were largely gone from Chinatown, history during the next twenty years would show these claims were incorrect. The growth of the tongs would help fuel greater gambling and opium use, and slumming parties would continue. And there might have even been a greater incentive to visit Chinatown because of the presence of the tongs, giving these visitors a greater connection to the perceived underworld of Chinatown. Tong violence might turn away respectable visitors to Chinatown, but those seeking to "live more on the edge," flocked to the neighborhood.

The article continued, praising Chinese restaurants. "Those who know Chinatown and the Chinese know and appreciate Chinese restaurants. Whatever else he may be, the Celestial is first and foremost a cook. Cooking, to the typical Chinaman, is far more than an art, more than a science. It is really a religion, and such it is regarded. To be a famous cook among the Chinese is to be a great man." It continues, "A fondness for Chinese edibles may be an acquired taste, but once acquired it becomes a habit. There are so many delicious dishes on a Chinese bill of fare which cannot be duplicated anywhere else. Nor can they be compared to any other dishes under the sun. They are thoroughly original and distinctive in both preparation and flavor."

Specifically, "The Chinese restaurants of Boston are fully up to the standard, and are supported largely by American patronage." And then the article noted, "A visit to a Chinese restaurant is incomplete without an inspection of the kitchen. It is the most scrupulously clean place on Earth,..." Chop Suey was then highlighted, mentioning that, "The first mouthful may not cause one to have a spasm of epicurean bliss, but there is something about it which makes one take a second and a third , and pretty soon the dish is empty. Another trial and the Chop Suey habit will be acquired."

But what is Chop Suey? It was described as, "There is the white meat of chicken, chopped fine, some white mushrooms, sliced but not chopped, sliced water chestnuts, some sprouts of beans, a dash of onion and a bit of celery. With this is served a dark brown sauce, which, if it must be confessed, tastes a trifle like turpentine, but is known as 'gee yow.' Gee yow is to the chef Celestial what Worcestershire sauce to tabasco is to the American. It is the flavor for the majority of his dishes." A number of other Chinese dishes are described in this article as well, all presented very positively.

The article finishes with, "There is plenty to interest one at any time in one of these restaurants, but especially between 10 o'clock and midnight." There is much diversity in the type of customers that can be found during these late hours, a great place for people watching.

There was trouble at the famed Hong Far Low in August 1903. The Boston Globe, August 10, 1903, reported that two boys met up with two girls at the restaurant, and it appeared that they hadn’t known each other for long. The boys were upset they couldn’t get hard liquor so they began to break furniture. They had to be physically thrown out by the Chinese and the fight continued on outside. A crowd formed and when the police arrived, they couldn’t easily get through, so one officer fired his weapon twice into the air. The two boys successfully fled the scene but the girls didn’t, though it appears they weren’t arrested.

It would also be during the first two decades of this century that "slumming parties" in the Boston area started to become popular. This was said to be a trend that started in London in the 19th century, and traveled to New York around 1884. In essence, well-off people went to poorer neighborhoods, such as Chinatown, as voyeurs, to experience what they perceived as the "seedier" areas. They wanted to temporarily live on the edge, to rub elbows with criminals and drug users, but with the ability to go back to their comfy homes afterwards. Eventually, there would even be tour guides offering slumming trips to various neighborhoods, including Chinatown.

Slumming Parties prohibited! The Boston Journal, June 28, 1903, ran an article titled, "Slumming Parties In Chinatown Forbidden By Police." The article stated, "Like all other large cities, Boston has its Chinatown. It lies in the vicinity of Harrison avenue and Oxford street, and through the by-ways and alleys which lead off from those and other contiguous thoroughfares at the most unexpected angles." In a positive spin, the article continued, "Just now, however, it's a very good little Chinatown...No more fan tan. No more pipe dreams." This meant that gambling and opium smoking had largely vanished. And as a direct result of Chinatown becoming more respectable, it had become "boring" in some circles, and "slumming parties" were less frequent. In addition, slumming parties had been semi-legally prohibited, though tough to enforce.

In addition, despite these police claims that gambling and opium smoking were largely gone from Chinatown, history during the next twenty years would show these claims were incorrect. The growth of the tongs would help fuel greater gambling and opium use, and slumming parties would continue. And there might have even been a greater incentive to visit Chinatown because of the presence of the tongs, giving these visitors a greater connection to the perceived underworld of Chinatown. Tong violence might turn away respectable visitors to Chinatown, but those seeking to "live more on the edge," flocked to the neighborhood.

The article continued, praising Chinese restaurants. "Those who know Chinatown and the Chinese know and appreciate Chinese restaurants. Whatever else he may be, the Celestial is first and foremost a cook. Cooking, to the typical Chinaman, is far more than an art, more than a science. It is really a religion, and such it is regarded. To be a famous cook among the Chinese is to be a great man." It continues, "A fondness for Chinese edibles may be an acquired taste, but once acquired it becomes a habit. There are so many delicious dishes on a Chinese bill of fare which cannot be duplicated anywhere else. Nor can they be compared to any other dishes under the sun. They are thoroughly original and distinctive in both preparation and flavor."

Specifically, "The Chinese restaurants of Boston are fully up to the standard, and are supported largely by American patronage." And then the article noted, "A visit to a Chinese restaurant is incomplete without an inspection of the kitchen. It is the most scrupulously clean place on Earth,..." Chop Suey was then highlighted, mentioning that, "The first mouthful may not cause one to have a spasm of epicurean bliss, but there is something about it which makes one take a second and a third , and pretty soon the dish is empty. Another trial and the Chop Suey habit will be acquired."

But what is Chop Suey? It was described as, "There is the white meat of chicken, chopped fine, some white mushrooms, sliced but not chopped, sliced water chestnuts, some sprouts of beans, a dash of onion and a bit of celery. With this is served a dark brown sauce, which, if it must be confessed, tastes a trifle like turpentine, but is known as 'gee yow.' Gee yow is to the chef Celestial what Worcestershire sauce to tabasco is to the American. It is the flavor for the majority of his dishes." A number of other Chinese dishes are described in this article as well, all presented very positively.

The article finishes with, "There is plenty to interest one at any time in one of these restaurants, but especially between 10 o'clock and midnight." There is much diversity in the type of customers that can be found during these late hours, a great place for people watching.

There was trouble at the famed Hong Far Low in August 1903. The Boston Globe, August 10, 1903, reported that two boys met up with two girls at the restaurant, and it appeared that they hadn’t known each other for long. The boys were upset they couldn’t get hard liquor so they began to break furniture. They had to be physically thrown out by the Chinese and the fight continued on outside. A crowd formed and when the police arrived, they couldn’t easily get through, so one officer fired his weapon twice into the air. The two boys successfully fled the scene but the girls didn’t, though it appears they weren’t arrested.

The Boston Herald, September 3, 1903, reported on the opening of a new clubroom for the Chinese Merchants' Association. The celebration included 90 minutes of firecrackers, which cost about $700, maybe the largest amount ever set off in Chinatown. The clubroom is located in a four-story brick building at 35 Harrison Avenue. There were also two banquets at the restaurant of Lock Sen Low, with 25 courses at each seating. Over the new building is a huge flag which states "On Leung Hong" which translates as "Peace & Wisdom Association."

The Pawtucket Times, September 9, 1903, mentioned Rev. C.H. Plummer had officiated at a number of marriages between Chinese men and white women. I've already mentioned Rev. Plummer in other parts of this series, as he appears to have been the main officiant for such marriages. Though it was technically legal for these couples to get married in Massachusetts, they usually had difficulty finding someone who would conduct the marriage. So, they commonly travelled down to Providence, Rhode Island, knowing Rev. Plummer would do the ceremony for them.

The first murder in Chinatown! The Boston Globe, October 3, 1903, reported that the night before, around 8pm, in front of 13 Harrison Avenue, Wong Yak Chung was shot and killed. Chung, who was 30 years old and lived at 48 Beach Street, was a member of the Hep Sing Tong. Two other Chinese were also shot, Ning Munn, 28 years old and of 19 Harrison Ave, who had a bullet wound in his right leg, and Yee Shoong Teng, 26 years old of 48 Beach St, who had bullet wound in his right leg and left foot. The police arrested two men, Wong Chin and Charlie Chin, 55 years old and of 2 Oxford place. Wong Chin was in possession of a .44 caliber revolver and was also wearing a chain mail shirt. It was also noted that the Hep Sing had been providing information to the police on illegal gambling in Chinatown.

“Boston’s Chinatown had its first murder last night,…” More details were provided in the Boston Herald, October 3, 1903. It was claimed that Highbinders were in town, the enforcers or "hatchet men" of the tongs, for a “deliberately planned system of assassination.” Wong Chin, 31 years old of Harrison Avenue, was the primary assassin, carrying a revolver and a “cunningly contrived axe,” a “short axe, not over a foot long, beautifully made, with a carved handle, and a nickeled blade sharpened to a razor end and controlled by a spring.” It was alleged that the tong problems started several months ago, when Wong Yak Chong came from San Francisco with the purpose of organizing the Hep Sing. Members of this tong informed the police of illegal gambling in Chinatown, their efforts directed against the On Leong tong, which then chose to take action, gunning down a few Hep Sing members.

The next day, the Boston Herald, October 4, 1903, printed another article about the incident, indicating the police feared there would be more violence in Chinatown, so a greater police presence was placed in the neighborhood. The Chinese provided various versions of the incident, and the motives behind it, so the police weren't sure as to the actual truth. The article also went into detail on the chain mail shirt worn by the assassin. “The coat of mail taken from the prisoner Wong Cheng is a curious garment. It is composed of a large number of pieces of sheet steel, each sheet about two inches square and a sixteenth of an inch thick. The squares ae joined by little bands of copper wire. The steel covering protects the back and sides of the wearer, as well as the chest and abdomen and would be impervious to a rifle bullet. It is made without sleeves. In fact, there is only one sleeve hole, the garment, which is covered with dark blue denim, being folded over the front and back of the wearer and tied over one shoulder and around the side with pieces of tape. At a distance it looks like an ordinary Chinese garment, but it weight about 15 pounds.” These mail shirts would be worn by a number of tong members at various times, giving them some protection against bullets and blades.

The Boston Herald, October 5, 1903, reported that the police stopped a suspicious Chinese man, Guey Tong, 18 years old of West Somerville, who was carrying a large bundle of alleged candy. Once he was searched, the bundle actually turned out to be 300 .38 caliber revolver cartridges, in 6 boxes of 50 each, and Suey couldn't explain the reason why he possessed the bullets. The newspaper the next day mentioned that Guey was released as it wasn't illegal for him to possess the ammo, and he didn't possess a weapon.

The police took action to stem the potential violence. The Boston Herald, October 6, 1903, mentioned that 3 Chinese men from New York City, who were visiting Boston relatives, were questioned by the police. The police felt they were suspicious, so they ordered the men out of the city who then left voluntarily. The police captain stated. “All strange and suspicious Chinamen will be promptly arrestd and sent out of the city if it is found impossible to prosecute them under the law. The vagrant and vagabond laws will be strenuously applied to the Chinamen and all ‘chinks’ without visible means of support will be prosecuted, the gambling will be stopped, so far as is possible, and sidewalk loafing by Chinamen will be stopped, as it was in the case of the Italians and Hebrews in the North End.” Maybe a bit extreme?

The article also gave more information about the murder victim, Wong Yak Chong, who was also known as Wong Kong and Charlie Wong. He lived at 20 Poplar Street in Roslindale, and had come from San Franciscos about three years ago. He ran a laundry for the last 3 years, was considered a very nice person and was a known member of the Hep Sing Tong. About 2 weeks previous to his murder, he had informed his friends he was planning to sell his laundry and travel back to San Frncisco to see his mother. He subsequently sold the laundry and then went to visit friends in Chinatown for several days, where he was killed.

More trouble for the Hep Sing. The Boston Post, October 9, 1903, under the headline, "Plots to Kill in Chinatown," noted that Sin Tuy, the president of the Hep Sing Tong, now had a price on his head of $3,000. The police were worried that there would be tong violence within the next 48 hours, and they also believed that many in Chinatown were heavily armed. including wearing chain mail shirts. It was thought that the violence might explode on Sunday, when Wong Yuk Chung was to be buried.

The Boston Post, October 10, 1903, provided a photo of the public announcement, a piece of red paper with black characters, with the price on Sin Tuy's head. It can be translated as, “On Sunday (next) kill all the Hep Sing Tongs. A reward of $3000 will be given for the life of C. Lieu Tuy.” However, the Boston Herald, October 10, 1903, reported that Tuy wasn't frightened. This announcement was posted on a public bulletin board on Oxford place, and this board seemed very important to the Chinese community as many different public announcements were posted there. The tongs would also use it to make their own pronouncements, especially against each other.

Interestingly, the Boston Herald, October 11, 1903, alleged that Tuy was only the Vice President of the Hep Sing, contrary to earlier reports that he was the President. The headquarters of the Hep Sing was also noted as being at 48 Beach Street.

The authorities took even more extreme measures to prevent tong violence in Chinatown. The Boston Herald, October 12, 1903, reported that U.S. marshals, immigrations officers, Chinese inspectors and Boston police arrested over 300 Chinese last night, starting their raid at the headquarters of the two tongs. If the Chinese couldn't produce registration certificates, then they were to be deported to China. The police captain thought this was the only way to stop the tong feud, believing about half the arrested Chinese would end up deported. The law which allowed these deportations was passed in 1882, and unfortunately the law didn't make provision for lost certificates. So, anyone who had lost their certificate would end up deported too.

The Boston Post, October 12, 1903, also reported that this was the biggest police raid in Boston history, with 258 Chinese arrested. Interestingly, the funeral the day before had gone off without incident. This raid was definitely a racist over reaction to some real problems with tong violence. In the end, the raid didn't prevent future tong violence, which would be even greater than the early October shooting.

Back to restaurant talk. It was mentioned in the Boston Herald, October 12, 1903, that "When slumming parties wish a glimpse of Chinatown they always peep in Hong Far Low's restaurant. It is the Delmonico's of Harrison avenue." More fame for Hong Far Low.

Racist fears about the dangers to young women from Chinese restaurants also arose at this time. The Boston Journal, November 1, 1903, in an article titled, Young Girls Of This City Consort With Chinamen, detailed some of the alleged dangers to young women in Chinatown. "The picture of a girl's ruination through the medium of the Chinese restaurant is too horrible to depict,...The Chinese restaurant is doubtless the most degrading phase of the great social evil..." The article continues that, "The suppression of the Chinese restaurant would mean the salvation of thousands of girls annually in America, in Boston alone of scores." The fears continued, mentioning, "...girls of very tender age, who ought to be at school or safe within their homes, may be found in these restaurants, hobnobbing over the little square tables with the Mongolians...in friendly contact with men pronounced to be the most unclean in morals and personal habits on the face of the globe."

No real evidence was presented of any actual problems, simply unsubstantiated allegations, and mentions how that if you visit a Chinese restaurant, you'll often see young women dining there, unaccompanied by any men. This racism would get even worse in the near future, as there would be attempts to legally prevent women from visiting Chinatown restaurants. I'll discuss those attempts later in this article.

A resolution to the first Chinatown murder! The Boston Journal, December 6, 1903, mentioned that Charlie Chin and Wong Chung were found guilty by a jury of murder in the second degree. They were alleged to be members of the On Leon Tong. Their sentencing was deferred but the penalty was life imprisonment. The Boston Herald, February 7, 1904, stated the two men had been sentenced yesterday to life imprisonment. The judge had over-ruled a motion for a new trial.

In December 1903, there was a brief mention of an unnamed Chinese restaurant at 46 ½ Harrison Avenue. And in April 1904, there was also a brief mention of an unnamed Chinese restaurant at 46 Beach Street.

The Pawtucket Times, September 9, 1903, mentioned Rev. C.H. Plummer had officiated at a number of marriages between Chinese men and white women. I've already mentioned Rev. Plummer in other parts of this series, as he appears to have been the main officiant for such marriages. Though it was technically legal for these couples to get married in Massachusetts, they usually had difficulty finding someone who would conduct the marriage. So, they commonly travelled down to Providence, Rhode Island, knowing Rev. Plummer would do the ceremony for them.

The first murder in Chinatown! The Boston Globe, October 3, 1903, reported that the night before, around 8pm, in front of 13 Harrison Avenue, Wong Yak Chung was shot and killed. Chung, who was 30 years old and lived at 48 Beach Street, was a member of the Hep Sing Tong. Two other Chinese were also shot, Ning Munn, 28 years old and of 19 Harrison Ave, who had a bullet wound in his right leg, and Yee Shoong Teng, 26 years old of 48 Beach St, who had bullet wound in his right leg and left foot. The police arrested two men, Wong Chin and Charlie Chin, 55 years old and of 2 Oxford place. Wong Chin was in possession of a .44 caliber revolver and was also wearing a chain mail shirt. It was also noted that the Hep Sing had been providing information to the police on illegal gambling in Chinatown.

“Boston’s Chinatown had its first murder last night,…” More details were provided in the Boston Herald, October 3, 1903. It was claimed that Highbinders were in town, the enforcers or "hatchet men" of the tongs, for a “deliberately planned system of assassination.” Wong Chin, 31 years old of Harrison Avenue, was the primary assassin, carrying a revolver and a “cunningly contrived axe,” a “short axe, not over a foot long, beautifully made, with a carved handle, and a nickeled blade sharpened to a razor end and controlled by a spring.” It was alleged that the tong problems started several months ago, when Wong Yak Chong came from San Francisco with the purpose of organizing the Hep Sing. Members of this tong informed the police of illegal gambling in Chinatown, their efforts directed against the On Leong tong, which then chose to take action, gunning down a few Hep Sing members.

The next day, the Boston Herald, October 4, 1903, printed another article about the incident, indicating the police feared there would be more violence in Chinatown, so a greater police presence was placed in the neighborhood. The Chinese provided various versions of the incident, and the motives behind it, so the police weren't sure as to the actual truth. The article also went into detail on the chain mail shirt worn by the assassin. “The coat of mail taken from the prisoner Wong Cheng is a curious garment. It is composed of a large number of pieces of sheet steel, each sheet about two inches square and a sixteenth of an inch thick. The squares ae joined by little bands of copper wire. The steel covering protects the back and sides of the wearer, as well as the chest and abdomen and would be impervious to a rifle bullet. It is made without sleeves. In fact, there is only one sleeve hole, the garment, which is covered with dark blue denim, being folded over the front and back of the wearer and tied over one shoulder and around the side with pieces of tape. At a distance it looks like an ordinary Chinese garment, but it weight about 15 pounds.” These mail shirts would be worn by a number of tong members at various times, giving them some protection against bullets and blades.

The Boston Herald, October 5, 1903, reported that the police stopped a suspicious Chinese man, Guey Tong, 18 years old of West Somerville, who was carrying a large bundle of alleged candy. Once he was searched, the bundle actually turned out to be 300 .38 caliber revolver cartridges, in 6 boxes of 50 each, and Suey couldn't explain the reason why he possessed the bullets. The newspaper the next day mentioned that Guey was released as it wasn't illegal for him to possess the ammo, and he didn't possess a weapon.

The police took action to stem the potential violence. The Boston Herald, October 6, 1903, mentioned that 3 Chinese men from New York City, who were visiting Boston relatives, were questioned by the police. The police felt they were suspicious, so they ordered the men out of the city who then left voluntarily. The police captain stated. “All strange and suspicious Chinamen will be promptly arrestd and sent out of the city if it is found impossible to prosecute them under the law. The vagrant and vagabond laws will be strenuously applied to the Chinamen and all ‘chinks’ without visible means of support will be prosecuted, the gambling will be stopped, so far as is possible, and sidewalk loafing by Chinamen will be stopped, as it was in the case of the Italians and Hebrews in the North End.” Maybe a bit extreme?

The article also gave more information about the murder victim, Wong Yak Chong, who was also known as Wong Kong and Charlie Wong. He lived at 20 Poplar Street in Roslindale, and had come from San Franciscos about three years ago. He ran a laundry for the last 3 years, was considered a very nice person and was a known member of the Hep Sing Tong. About 2 weeks previous to his murder, he had informed his friends he was planning to sell his laundry and travel back to San Frncisco to see his mother. He subsequently sold the laundry and then went to visit friends in Chinatown for several days, where he was killed.