|

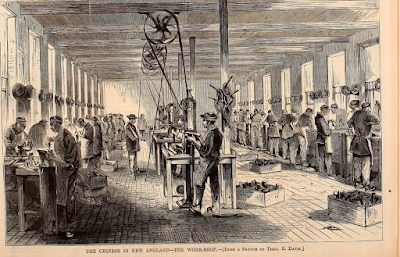

| Harper's Weekly, July 23, 1870 |

Until June 1870, there were only a handful of Chinese living in Massachusetts. The Boston Globe, September 19, 1873, discussed some of the findings of the 1870 census. The city of Boston, with a population of 250,526, didn't have any Chinese residents. The communities of Brighton, Cambridge, West Roxbury and Charlestown also didn't have any Chinese residents. Somerville and Brookline each had a single Chinese resident listed in their census results. Although not part of the census, it’s known there were a handful of Chinese scattered in other communities, such as Chelsea and Malden, but overall, the Chinese were clearly a rarity in most of Massachusetts. However, in June 1870, there would be the first significant influx of Chinese, mostly young men, into Massachusetts.

Back in 1865, Chinese started to work on the construction of the transcontinental railroad, and it's said that by 1867, 90% of those railroad workers were Chinese. The completion of the railroad at the end of that decade led to significant unemployment among the Chinese. The 1870s also saw a nation-wide depression, which led many Chinese to leave California and spread across the U.S., seeking employment. Many came to the East Coast, where manufacturers were willing to hire, except that they often paid them less than they did the previous white workers the Chinese replaced.

On June 15, 1870, 75 Chinese workers arrived in North Adams, Massachusetts, to work at a shoe factory owned by Calvin T. Sampson (usually known as C.T. Sampson). Over the next ten years, additional Chinese workers would arrive in the village to work at the shoe factory, while some of the existing workers would return to San Francisco or even China. In 1880, when all of the Chinese workers left the factory, only a few remained in Massachusetts.

First, a little information about North Adams. This village was part of Adams until they officially split in 1878. The Springfield Republican, June 26, 1872, mentioned that there was a “A little pamphlet styled ‘The Attractions of North Adams,..’ and it stated that North Adams, with a population of about 9,000, was “emphatically a self-made town.” In January 1873, another source alleged the population was about 13,000. Today, it’s population is still only about 13,000 people. It was also a mill town, with a number of manufacturing businesses from shoes to bricks, marble to iron.

The pamphlet continued, noting that all the leading business men and wealthy citizens, “of which there are many,” are self-made men. C.T. Sampson would be one of those self-made men. It was also mentioned that, “Its population is largely foreign, and the Irish portion, as in other towns, devote Sunday afternoon and evening to getting drunk and quarreling more than they ought.”

Second, who was C.T. Sampson, the man willing to hire a number of Chinese to work in his shoe factory? Sampson was born October 2, 1826 in Stamford, Vermont, and his parents owned a farm. His family descended from Abraham Sampson, who came to Plymouth, Massachusetts in 1629. When Sampson was 19 years old, his father died, so he had to carry on the work on the farm and tend to his mother and sister.

However, everything changed when he made a visit to North Adams in the late 1840s, which was about five miles south of Stamford. Sampson met George Millard, who might have been a cousin. George had partnered with two other men and they had purchased a stock of boots and brogans from a company that went bankrupt. Millard persuaded Sampson to help sell the shoes. Sampson then went door to door, and sold all of the shoes within three days, with a profit of $25. This apparently fueled a new ambition in Sampson and he soon after moved to North Adams.

In 1849, when he was about 23 years old, he married Julia Hayden of Clarksburg, and they would stay together for the rest of their lives. In the Spring of 1851, Sampson travelled a good distance to Boston to obtain more shoes to sell. At first, he continued walking door to door, but eventually obtained a horse and wagon, allowing him to also visit the nearby villages and towns.

Once he had acquired savings of $100, he opened his own retail shoe shop. There was a major setback in 1853, when a large fire destroyed his shop, as well as other adjoining buildings, but he quickly rebuilt. In addition, from 1854-1858, he started making his own shoes, opening the first shoe factory in North Adams on Eagle Street.

Sampson was quite successful, and in 1857, when he was about 31 years old, he started construction of a “large mansion on South Church street” which was said to be “one of the finest in that part of the village of North Adams.”

It was noted in The Commercial Bulletin, October 20, 1860, that “C.T. Sampson, manufacturer of ladies’ shoes, is doing a very prosperous business, which by his integrity and promptness is fast increasing.” There were other shoe manufacturers in North Adams at this time, including George Millard (Calvin’s cousin), who employed about 50 people and had annual sales of about $70,000. There was also Ingraham’s Bro.’s, which made about $25,000 of boot and shoes annually, and G.T. Southwick, a very small boot and shoe manufacturer.

Sampson was so successful that around June 1863, he opened a shoe store in Boston at 30 Pearl Street, selling the shoes he manufactured. It was also in 1863 that Sampson introduced pegging machines into his factory. The Commercial Bulletin, August 8, 1863, noted: “The establishment of C.T. Sampson, for the manufacture of women’s, misses and children’s pegged boots and shoes, is in operation. He has four pegging machines, three of them the ‘New Era’ pattern, which is run by a steam engine. A shoe is pegged on one of these machines in eleven seconds of time. This is the most extensive shoe manufactory in this part of the State, having the capacity to turn our 1,380 pairs a day.”

At this time, many manufactured shoes were sewn together, but pegging (using wooden or brass pegs to hold a shoe together) reduced the time and cost of making shoes. So, the pegging machines made Sampson even more competitive, as well as saving him much time and expense.

The Berkshire County Eagle, February 22, 1866, provided a little information on Sampson’s business, noting he had 80 employees and his monthly pay roll was $2,120, an average of $26.50 per employee. In comparison, George Millard & Co. had 55 employees and a monthly payroll of $1,558, an average of $28.33 per employee. These figures will be especially interesting when we later examine the monthly wages that Sampson allegedly paid his Chinese workers.

Further details of Sampson’s shoe factory were provided in The Commercial Bulletin, October 19, 1867. “C.T. Sampson, of North Adams, has one of the largest shoe factories in the Western part of the State. He occupies a building 90 by 60 feet, and three stories high, employs 75 hands, and turns out 50 cases (of 60 pairs each) of shoes per week. Most of the work in this establishment is performed by machinery propelled by steam. The annual consumption of upper leather is 225,000 square feet, and of sole leather 65 tons, and the annual sales foot up $20,000.”

In 1868, Sampson began to have serious labor problems at his shoe factory, which even led to him being physically assaulted. The Springfield Republican, June 10, 1868, reported, “For two weeks past the hands of C.T. Simpson have stopped work, in consequence of his employment of a Mr. St. Johns, who was obnoxious to their organization. On Monday evening Mr. Sampson was called out of his house and brutally attacked by three men with clubs and other weapons, who wounded him severely. Mr. Sampson expects forty workmen from Canada to take the places of those who left.”

Despite his injuries, Sampson wasn’t willing to give into the demands of the striking workers. The Springfield Republican, July 30, 1868, noted “C.T. Sampson of North Adams has conquered the strike in his shoe manufactory and is now running it with a full force of workmen. He secured 43 in Montreal, last week, and employs none who belong to the St. Crispin union.”

Who were these Crispins? The Order of the Knights of St. Crispin, originally formed in Scotland, founded a branch in the U.S. in 1867. St. Crispin was the patron saint of cobblers. The Order was a labor union of shoe workers, primarily based in the northeast region of the U.S., and may have eventually reached over 50,000 members. There was a vocal element of the Crispins who were quick to want to strike, and fought to prevent the introduction of new shoe production machinery and the hiring of immigrants.

The Berkshire Eagle, March 7, 1956, would give more explanation of the motivations of the Crispins. “The specific issues in the North Adams dispute involved the mass production techniques introduced into the shoe industry during the Civil War. Demands for more shoes led to the invention of machines that cut, nailed and sewed shoes in greater quantities, and the shoemakers saw that their days as skilled craftsmen were numbered.” The article continued, “The cobblers attempted to turn back the tide of machinery by organizing the Knights of St. Crispin. The union had three main objectives: To exclude all except sons of shoemakers from the trade; … to hold the price of shoes at the level prevailing before mass production; and to maintain a union shop."

From 1868-1870, the Crispins would cause a number of issue for Sampson, striking at times, and other times refusing to grant any concessions requested by Sampson. It was these problems which eventually led Sampson to hire Chinese workers.

But first, around November 1868, Sampson closed his shoe factory to make some extensive repairs and renovations, noting the factory would be operating once again in early December.

The Commercial Bulletin, March 20, 1869, noted that Sampson currently employed about 150 people, and they produced about 85 cases of shoes (5100 pairs) each week. It was also mentioned that the factory used 30 sewing machines, as not all of their shoes were pegged. The article also noted, “These goods bear an excellent reputation and are in demand in all sections of the country.”

Sampson’s business was so successful that around October 1869, he sold his shoe factory and purchased a former cutlery building, located on Holden Street, investing $20,000 to renovate the building so he could manufacture even a larger amount of shoes.

The Commercial Bulletin, April 9, 1870, described the new building; “It is of brick, three stories, with a front of 115 feet and a depth of 120. All the rooms are heated by steam, and an engine of 20 horsepower drives the machinery. The building is divided into departments—the sole-leather room, bottomer’s room, stitching room, &c., & c., and is arranged in every part with a view to facility of work and comfort of the operatives. All the boxes used for packing shoes are made on the premises. The establishment gives employment to 160 hands, which number will soon be increased to 200, and turns our 120 cases of ladies’ and misses’ shoes per week. Every week over three tons of sole leather is consumed, besides 12,000 feet of upper leather and 1,500 yards of cotton drilling for linings.”

Sampson’s problems with the Crispins exploded in 1870. In January, the shoe workers demanded an advance of one dollar per case of shoes and Sampson refused their demand. In response, a number of shoes started being made in an inferior manner, an obvious intentional action in response to Sampson’s refusal of their demand. Sampson asked the foreman for an explanation, but none was given. Sampson then fired some of the workers who made the inferior products, and hired new people. These new people did well for a few days, and then the quality of their work also diminished. These problems continued into April.

At that time, Sampson told his workers that business had been poor recently, and asked if they would accept a 10% reduction in their wages until business got better again. The Crispins voted to refuse the reduction, and then they quit the factory. In May, Sampson hired a new group of workers, all Crispins, and though they traveled to the factory from a nearby town, they declined to go to work. These workers had spoken to the former Crispin employees, and told Sampson that according to their rules, they couldn’t work for him.

On May 13th, at around 10am, the new group of Crispins returned home to North Brookfield, leaving Sampson with no workers. And at 4pm that same day, Sampson sent his trusted clerk, George W. Chase, on a train to San Francisco. George’s mission was to hire a crew of Chinese to work in the shoe factory.

It’s unknown for how long that Sampson had been considering hiring Chinese workers. It’s clear that his labor problems had been going on for two years, and that other shoe factories, in Massachusetts and in other states, had been having similar problems with the Crispins. At the time, it was a radical solution to hire Chinese workers, but Sampson was probably desperate to a degree, not wanting his shoe factory to fail, but unwilling to give into the continued demands of the Crispins.

One month later, on June 13, 75 Chinese workers arrived by train in North Adams, headed to Sampson’s show factory.

The Berkshire County Eagle (Pittsfield), June 16, 1870, reported on the arrival of the Chinese workers, albeit with a racist view even though the writer was supportive of the idea. "We had an excitement at North Adams yesterday, consequent upon the arrival of Mr. Sampson's seventy-five celestial rat eaters, from San Francisco. The streets were thronged from the depot to Mr. Sampson's spacious manufactory, with a crowd of people eager to witness the advent of the Chinamen. I was disappointed in their appearance, for as they marched along they looked neat, smart, and intelligent. Most of them are young, and had a merry twinkle with their eyes. The old employees of Mr. Sampson, together with many other laborers, are very indignant at him for this importation, wishing and prophesying all kinds of bad luck to him; but I believe Mr. Sampson will make the thing work; he is not the man to fail. In his boyhood he accomplished what he undertook and has done the same ever since, showing a truly wonderful amount of muscular power to execute, as well as mind to plan, together with much tenacity of purpose. Go ahead Mr. Sampson, I wish you success."

The article also mentioned, “Upon their arrival to the depot here a scene ensued to which the people of this town are strangers. Fully two thousand people, men, women and children, assembled to catch a view of the Celestial strangers, and although some indignities were offered they were discountenanced by the mass of the citizens. A few such as are always in spirit for the recurrence of a holiday in the absence of other excitement, indulged in hoots and jeers as the dusky procession, in couples, headed by Messers. Sampson and Chase, and flanked by a posse of a dozen policemen, marched toward the manufactory. When nearly there, one man threw a stone and another struck one of the new citizens, but they were quickly arrested and locked up. I am glad to record that the Crispins and the shoemakers generally strongly discountenance any act of this kind and am assured that they will be no more subject to molestation, than any other persons. They are not blamed for coming hither.”

In addition, it was stated, “Ah Sing, or Charlie, as he is familiarly called, comes with them. He is passably well educated and is a regular member of the Methodist Episcopal church. He will keep all the accounts, receiving the wages, purchasing their food and giving them spending money and sending each month the residue to the Kwong Chong Twing Company of San Francisco, which will keep it on deposit for them. The men are very neat in appearance, which is a subject of general surprise.”

There was another lengthy article in the Pittsfield Sun, June 16, 1870, also with a racist tone. The article began, “The van of the invading army of Celestials, seen in a vision by Wendell Phillips, greatly feared by all democrats, and not particularly welcomed by any body except in dire necessity, have arrived at Chicago and will reach Massachusetts, this week, in the persons of 75 Chinamen engaged by C.T. Sampson to man his shoe factories, and free him from the cramping tyranny of that worst of American trade-unions, the “Knights of St. Crispin.” Although the newspaper attacked the Chinese, it also didn’t view the Crispins in a good light eithert.

The article then alleged the details of the contract between Sampson and the Chinese, but I’ll note that the validity of these details would be later contested by Sampson, who would remain tight-lipped concerning the details of the contact and the amount he paid to the Chinese workers. The newspaper claimed they were to be paid $23 a month for the first year, and $26 a month for the second and third years. The foreman, Ah Sing, was supposed to be paid $60 a month. In addition, Sampson paid for their railway passage from San Francisco, and would supply them with room and fuel.

It was also claimed, “The most sacred part of the Chinaman’s religion, his body’s burial with his ancestors, is also nominated in the bond. Sampson is pledging to box up each corpse and send it to Kwong Chong Wing Co. in Frisco, who will take charge of the rest of it.” Sampson would later deny this was part of the contact.

There was a second article in this newspaper, a reprint from the New York Herald, spreading irrational fear of the Chinese. It stated. “We fear there is mischief for Massachusetts in this experiment. It is manifestly an experiment against the shoemakers’ unions of that State, and, if successful, it may lead to an overwhelming invasion and occupation of Lynn and all the other shoemaking towns in the State by the Chinese. Then Lowell and all the other cotton and woolen manufacturing cities and villages in the State will be supplied with Chinese operatives, and the Yankee factory boys and girls, bag and baggage, will have to clear out; and so Massachusetts, in the course of twenty years or less, may become a Chinese settlement, with the Puritans subject to the Mongolian balance of power and the Puritan religion overshadowed by the worship of Buddha.”

Around this time, the newspapers also noted that the Crispins had decided to form their own co-operative to manufacture shoes, to become competitors to the show factories which refused their demands. Interestingly, the Berkshire County Eagle, June 16, 1870, reported that the other shoe manufacturers in North Adams now demanded a reduction of 10% of the wages of their workers, the same demand Sampson had originally made to his workers.

The Crispins held a meeting to discuss the demand, and they agreed to this reduction! Only two months ago, they had refused Sampson when he had made a similar demand. If the Crispins had accepted Sampson’s demand in April, then it’s very possible Sampson might not have hired Chinese workers to replace them.

In response to the arrival of the new Chinese workers, the Berkshire County Eagle, June 23, 1870, reported that the legislature tried to push a resolution to declare any contracts with the Chinese longer than 6 months to be void but House voted against it. The legislature was clearly aware that the Chinese workers had three-year contracts.

|

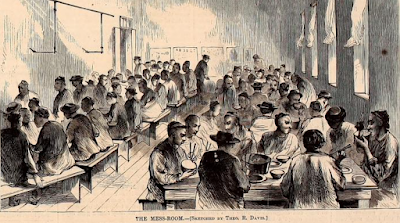

| Harper's Weekly, July 23, 1870 |

Many more details of the Chinese and their work at the shoe factory were provided in the Pittsfield Sun, June 30, 1870, reprinting an article from the Albany Evening Times, June 22. An Albany reporter went to North Adams to investigate the matter and speak to Sampson. The reporter noted, “From what our reporter had read, and what he had heard, he was prepared to see a harsh, selfish, and unprincipled sort of a person, whose only aim was to get all he could from his employees by giving as little as possible in return. Our reporter, however, feels it is his duty to state that Mr. Sampson is no such man. He is a gentleman, well to do in this world, and who has accumulated a snug property by close attention to business, and who thinks he has a sort of right to control said property according to his own wishes. He is about forty years of age, and has evidently been a hard-working man.”

He also mentioned that the shoe factory is situated on one of the principal streets. “It is a fine, well proportioned, four story brick building, in the midst of a beautiful enclosure, and everything about it bears the appearance of neatness and thrift.”

Sampson told the reporter that, “… as far back as last January he had great complaints from his customers of the quality of his work, which was being returned to him as unsaleable.” His spoke to his workers but it did no good. He then imported some additional Crispins from Brookfield, but they remained only a few days. Sampson didn’t want to give into the demands of the union, so he sought elsewhere for workers.

Sampson stated he had incurred an expense of nearly $10,000 to bring on the Chinese, plus the loss of time and business while training them. He noted, “… he is working for a principle, and not money, and he is bound to see it through.”

The reporter visited the quarters of the Chinese workers. “One room is used for a sleeping apartment. The arrangement is similar to the bunks on a ship, and consists of a double row of berths passing through the centre of the room, and a single row on each side. A nice mattress, with blankets, is placed in each bunk, and a curtain is arranged to shut out the light. The room is high, and admirably ventilated, and presents an appearance of neatness and cleanliness, which must result in the perfect health of the occupants.”

|

| Harper's Weekly, July 30, 1870 |

There was another plain room, with tables and benches, where the Chinese ate. “Their food consists of rice, with occasionally some meat or potatoes. Their drink is black tea, of which they keep a supply constantly on hand, and drink as freely as Americans do of water.”

The reporter also mentioned, “They all seemed as happy and as free from care as children. Their habits are uniformly good—not one of them uses intoxicating liquors, and only four of the seventy-five smoke.”

It was also stated that none of the Chinese knew anything about making shoes before arriving in North Adams. However, “The first day three were set at work, and yesterday, there were already twenty-three at work, some of them perfectly competent to work by themselves, although it is barely a week since commencing.” They were clearly intelligent, quick and willing to learn a new trade.

Sampson told the reporter that all of the prior news articles about the amount of pay for the Chinese workers were wrong, but he wouldn’t talk about the exact amounts. Plus, he stated he never agree to send their dead bodies back to San Francisco.

Of the 75 Chinese, nearly all of them were from 16-22 years old, and some had families in China. Two of them were around 35 years old, including their cook. The Chinese workers were chosen from a pool of about 2000 Chinese who had all desired to learn the shoe trade. “They all came of their own free will and accord, the only fee paid being a charge of one dollar per head, paid to the intelligence agent.”

|

| Harper's Weekly, July 30, 1870 |

Their leader, interpreter, foreman and manager; was Ah Sing, also known as Charlie, who was 22 years old and had been in the U.S. for eight years. He was fluent in English and could read it as well. He was also a member of the Methodist church. He told the reporter that the workers were divided into 3 companies, and each company were all cousins.

The article also noted, “The majority of the citizens of North Adams, outside the labor organizations, are fully committed to Mr. Sampson’s views, and intend to stand by him to the end.” Finally, it was mentioned that, “It was used as an argument against the Chinese, that they would spend no money on the place, and that trade would be diverted thereby. They have already purchased between four and five hundred dollars worth of clothing, and are using some meat, and potatoes,..”

The primary opposition to the Chinese remained the Crispins. The Berkshire County Eagle, June 30, 1870, reported on a meeting the Crispins held on June 23, attended by three to four thousand people, to discuss the Chinese. The Crispins claimed they wouldn't oppose the Chinese if they had come as legal workers, and not slaves. As that was the case, and even admitted by the Crispins, then they shouldn’t have opposed the Chinese at all. One of the speakers at the event stated, “He disclaimed any intention of inciting violence against Mr. Sampson or his Chinese workmen, but did not scruple to denounce or ridicule both.”

The writer of this article also claimed to have seen Sampson’s contract with the Chinese, and stated there wasn’t any agreement to return any dead bodies to California.

The first known injury! The Pittsfield Sun, July 7, 1870, reported that Charles Sing, the Chinese foreman, had his thumb cut off by some of the shoe machinery. The article didn’t provide any other specifics so it’s unclear whether it was only a small part of his thumb or the whole digit. However, no other newspapers ever mentioned this injury, or that Sing had any type of disability from this alleged injury. Thus, it seems likely it was a relatively minor injury.

More opposition to the Chinese workers! The Berkshire County Eagle, July 21, 1870, reported on Jennie Collins, a Lowell Factory girl, who recently addressed a Labor Reform meeting in New Bedford. To a crowd of about 2000, Jennie stated her “...object was to denounce the poor coolies,…” Jennie continued, “She reviewed the condition of labor in Massachusetts, declaring it to be worse than in England, and she denounced the legislature for not passing laws in favor of the workingmen and against the capitalist.” Continuing, “The shoe monopoly is one of the greatest in the United States. It was formed when the introduction of the sewing machine and other improved machinery enabled the bosses to fill their orders in Winter,…”

In addition, she said, “But the workmen have learned the value of organization in the army, and instituted the order of Knights of St. Crispin, and a good order it is. By its uniformity it regulates the shoe trade, and makes better citizens of the shoemakers,..” She also claimed, “They did not dare try it in Lynn or Brookfield, where the shoemakers are in great numbers, but in North Adams where there is only one factory.” The last bit was untrue as there were at least four shoe factories in North Adams.

More information on the eating habits of the Chinese workers was mentioned in the Pittsfield Sun, August 4, 1870. “Rice is the principal component of each meal, and it is flanked by nothing more disgusting than beef, fish, or pork, cooked with vegetables in ordinary style. An average dinner will comprise beef or pork, boiled potatoes, beans and other ‘garden sass,’ and the inevitable rice and tea. Supper and breakfast are made from rice, with a fish sauce resembling in appearance anchovy, string beans, etc. and tea. The scrupulous neatness of the cook and the kitchen utensils is commented on by all,..”

As I previously mentioned, the Crispins had sought to create a new shoe co-operative, and around August 1870, the new North Adams Co-Operative Shoe Company was established, with a capital stock of $6,000 and the President was Oliver K. Wood. The company purchased an existing shoe factory and started with 30 members.

Sampson was probably unworried about this new co-operative, especially considering its small size, and the Pittsfield Sun, August 11, 1870, discussed how pleased he was with his Chinese workers. He stated that only 4-5 of them weren’t doing so well, and that he might send them back to San Francisco. He was even thinking about hiring 50 more Chinese workers to enhance his production.

Another newspaper claimed to have seen a copy of Sampson’s contact with the Chinese, but we can’t be sure whether it was legitimate or not, especially as the wage amounts were similar to what Sampson had previously denied.

The Berkshire County Eagle, August 25, 1870, reported that the contract was between Sampson and Ah Young & Ah Zan (or Yan) of San Francisco to furnish workers for him, including 72 men, 2 cooks, and 1 foreman. The foreman was to be paid $60 per month for overseeing 75 men, and 50 cents for each extra man if any were added. Everyone else received $23 per month for the 1st year, and $26 for the 2nd and 3rd year, and $28 after that. Room, wood and water were to be furnished for free. The men would work for 11 hours per day from March 20-September 20, and 10.5 hours for the rest of the year. These were typical working hours in the manufacturing industry during this time. Railroad passage to North Adams was included free, and the return trip would be free if they worked satisfactorily for 3 years.

As previously mentioned, in 1866, Sampson was paying his employees an average of $26.50 per month. Thus, if the above wages were accurate, he was paying the Chinese workers only a slightly smaller amount than he had paid his white workers. Plus, Sampson was providing them room, wood, and water for free, which would make up for any shortfall in wages. However, there would later be allegations that Sampson had paid his previous Crispin workers $15-$20 per week, meaning he would then have paid the Chinese workers much less. Sampson’s unwillingness to discuss the wages of his Chinese workers could be indicative that he knew he was paying them low wages and didn’t want to publicly admit it.

We also have to consider that the Chinese wages were negotiated with Sampson by a Chinese firm in San Francisco. The workers themselves didn’t negotiate for their wages. So, if the wages were low, part of the blame has to extend to the Chinese firm which negotiated the contract.

The Springfield Republican, September 26, 1870, and Berkshire County Eagle, October 6, 1870, both reported that Sampson now estimated the cost of his Chinese workers at around $30,000. Sampson though was “well satisfied thus far with the result.” And it was said, “He already saves two dollars in the cost of manufacture, on every case of boots made, and expects bye-and-bye to save six dollars.” So, in three months, the Chinese workers, who had no prior experience, were already performing so well that they were saving Sampson money. However, it’s unclear how much of those savings were due to lower wages.

The New England Farmer, October 8, 1870, mentioned that the Chinese workers were doing well and had already sent $1600 back to San Francisco, thought to help reduce some of their debt, such as the costs they had paid to cross the Pacific from China. The article also briefly mentioned, “They have given lavishly to beggars asking alms beneath their windows.” In addition, it was noted, “They have taken great care of cleanliness, bathing very frequently.”

The Berkshire County Eagle, November 24, 1870, discussed that about 20 of the Chinese workers attended public worship every Sunday, and that about 60 of them attended Sabbath school in their own quarters. Plus, it was reported, “Mr. Sampson says his losses from work returned have been far less since the advent of these workmen than before.”

More details of their Sunday school was provided in the Berkshire County Eagle, December 1, 1870. The school is held “… in a long, low room in the factory building.” Classes started about 4pm on the Sabbath, lasting for about 45 minutes. The sessions also included lessons in English. The teachers included older men, young girls, and even some young boys, aged 12-14 years. In fact, the first person to help teach the Chinese was a 12 year old boy who showed up soon after they arrived with a primer. So far, the Chinese have attended 16 Sunday school sessions.

Near the end of November 1870, most of the shoe factories in North Adams closed until January. However, Sampson’s factory and the Crispin co-operative continued to operate during this time.

Their first Thanksgiving! The Springfield Republican, November 29, 1870, told the story that Sampson provided turkeys and thanksgiving fixings to his Chinese workers, who were very happy about this feast. In addition, a large group of them attended the Baptist church on Thanksgiving day where Rev. Mr. Gritlin preached the sermon.

The Springfield Weekly Republican, January 13, 1871, reported that a meeting of the New England Shoe & Leather Dealer’s Association was held in in Boston. At the meeting, it was stated that the hide and leather and boot business of New England amounted to about $200,000,000 a year! At this meeting, Sampson was selected as one of the new directors of the association.

Let’s start a band! In January 1871, the Chinese workers decided to organize a brass band, and recently received some instruments, including two drums, one gong, one pair cymbals, and a clarionette. Then, the Springfield Republican, February 20, 1871 and the Pittsfield Sun, February 23, 1871, reported on the Chinese workers celebrating Chinese New Year. They were permitted to take off work from Friday until Tuesday morning. For their celebrations, they invited local clergy, their Sunday school teachers and some others.

First, the celebrations began with a musical reception, and the Republican stated, “The band has been practicing for two weeks, and has attained a proficiency pronounced equal to San Francisco professionals by those who have heard both.” Quite an impressive feat! Then, there was a feast, mostly American dishes, and over 150 guests were served dinner. Later on that day, firecrackers, on long poles, were stuck out the windows and caused quite loud noises. Unfortunately, they had planned a parade for the next day, but it rained so they had to cancel their plans.

About ten months after their arrival, one of the Chinese workers was said to have returned to San Francisco, although few details were given initially. Later information though indicated Sampson sent the man home as he wasn’t working out well in the factory.

The Weekly American Workman, April 22, 1871, mentioned the Chinese workers. “Again, as regards the work turned out, it far excels that of white men, both in finish and otherwise. The Chinaman can do as much or more in the same number of hours as a white man, and make better work.” The article also stated, “As citizens, they conduct themselves peaceably and are on good terms with all---"

More positivity! The Pittsfield Sun, August 31, 1871, reported that Sampson now claimed that his Chinese workers had saved him $40,000 in the past year as they produce 10% more work in a day than the previous Crispin workers. For specifics, the Pittsfield Sun, September 14, 1871, reported that last week, the Chinese workers produced 13 cases of shoes, a total of 7800 pairs of shoes (600 shoes per case).

The Berkshire County Eagle, November 16, 1871, noted that a group went to investigate the shoe factory, as they desired to know whether a small group of Chinese workers could be hired for farm labor. The group saw the Chinese working, with a few “American boys and girls,” noting the Chinese were hard workers with pleasant dispositions. This is the first mention that white workers were also working with the Chinese in the shoe factory. There's no mention whether these white workers were part of the Crispins or not.

Some of the Chinese were operating the pegging machines, and their great skill was noted. It was also claimed that the Chinese workers received a wage of $26 per month. It was also said that most of the North Adams residents were favorable to them, except for the Irish shoemakers (mostly, if not all, Crispins). Finally, the group decided that they wanted to send to San Francisco to hire 10 Chinese workers to work their lands.

Turkey gifts for Turkey Day. Last year, Sampson bought turkeys for his workers, but this year, Charlie Sing, the Chinese foreman, bought 15 turkeys and sent them as Thanksgiving presents to different ministers and Sunday school superintendents. The Berkshire County Eagle, December 7, 1871, stated, “This is the most recent of many generous gifts of his.”

Positivity about the Chinese workers. The Christian Era, December 14, 1871, noted, “The Chinamen are eager to learn our language, and one of them has a teacher who gives instruction every evening, earning liberal pay for the service.” The article continued, “A goodly number of these Chinamen attend church and Sabbath School.” The article also stated, “None of them gravitate towards liquor or gambling saloons.” Finally, it ended with, “In a word, their prominent characteristics are, industry, ingenuity, fidelity, neatness, economy, power of discrimination, and love of learning.”

How much were the Chinese workers paid? The Springfield Republican, December 29, 1871, claimed that the prior Crispin workers had been paid about $15-$20 a week, but the Chinese were only paid about $23 a month. However, the exact amount of the Chinese wages was never actually confirmed, and had even been denied by Sampson. None of the references ever mention anyone asking the Chinese workers the amount of their wages.

During the past almost two years, only two of the Chinese workers had returned to San Francisco. The Boston Globe, March 5, 1872, reported that one worker left on his own, “not liking our climate,” while Sampson sent one back as “intractable.” The article also noted, “their dexterity, their diligence, their earnestness---“ and that their rooms were scrupulously clean. “In the dining room one of their number keeps an exact record of their expenses written upon the wall in Chinese characters, where it can be examined by each member. The weekly expense for each person for food, &c., is about two dollars and a quarter.”

So, the monthly expense for each Chinese worker was about $8.50, which might be only about one-third of their monthly wage, allowing them to save a good amount of their wages.

The article continued, “Outside the factory all have entire freedom.” They were not barred from any business in North Adams. Even those locals who had originally opposed the idea of hiring the Chinese workers, had little negative to say about the Chinese and offered no hindrance to them. In addition, “No death has occurred since the party arrived here, nor has there been a serious case of sickness.” Finally, the Chinese workers were asked if they planned to return home once their contract term was over. However, they were reticent to commit to a decision.

There was a brief mention in the Springfield Republican, April 4, 1872, that Sampson was dangerously ill, although his disease wasn’t specified and there wasn’t any follow-up information in the newspaper. There wasn’t any information on how it might have affected the shoe factory.

Fortunately, Sampson seemed to improve relatively quickly. The Boston Semi-Weekly Advertiser, April 30, 1872, discussed the Bureau of Statistics of Labor and their visit to the shoe factory. “The bureau thought itself treated rather hardly on the occasion of the visit to Mr. Sampson’s show factory at North Adams.” They had visited the prior year as well, and Sampson had once again refused to provide them any information about his Chinese workers, stating he would only do so if compelled by the law. However, he did make a concession and agreed to fill out a form with some information and mail it to the Bureau.

Sadly, the Boston Globe, August 30, 1872, reported that Quain Tung Tuck, 20 years old and one of the Chinese workers, died of rheumatism of the heart. This was the first death among the Chinese shoe workers.

More Chinese workers arrived! First, the Pittsfield Sun, September 4, 1872, mentioned that the original contract with the Chinese workers would end its term in June 1873. Then, it was thought they would all return home and other Chinese workers would arrive to replace them. However, the Boston Globe, November 28, 1872, reported that 30 more Chinese workers had arrived at the shoe factory two days ago, making the total 103.

A valuable gift! The Congregationalist, January 9, 1873, noted that Sampson had gifted Charles Sing, the foreman of the Chinese workers, a watch and gold chain that was worth $200 (about $5,000 in today’s dollars). The article stated, “They call it a testimonial of esteem.”

And even more Chinese workers. The Berkshire County Eagle, January 23, 1873, stated that 22 additional Chinese workers had arrived by railway, making it a total of 113 workers, although that total might be a mistake. There were 103 Chinese workers two months before, and no indication that ten, or even one, had left the factory during those two months.

Turkey gifts for Turkey Day. Last year, Sampson bought turkeys for his workers, but this year, Charlie Sing, the Chinese foreman, bought 15 turkeys and sent them as Thanksgiving presents to different ministers and Sunday school superintendents. The Berkshire County Eagle, December 7, 1871, stated, “This is the most recent of many generous gifts of his.”

Positivity about the Chinese workers. The Christian Era, December 14, 1871, noted, “The Chinamen are eager to learn our language, and one of them has a teacher who gives instruction every evening, earning liberal pay for the service.” The article continued, “A goodly number of these Chinamen attend church and Sabbath School.” The article also stated, “None of them gravitate towards liquor or gambling saloons.” Finally, it ended with, “In a word, their prominent characteristics are, industry, ingenuity, fidelity, neatness, economy, power of discrimination, and love of learning.”

How much were the Chinese workers paid? The Springfield Republican, December 29, 1871, claimed that the prior Crispin workers had been paid about $15-$20 a week, but the Chinese were only paid about $23 a month. However, the exact amount of the Chinese wages was never actually confirmed, and had even been denied by Sampson. None of the references ever mention anyone asking the Chinese workers the amount of their wages.

During the past almost two years, only two of the Chinese workers had returned to San Francisco. The Boston Globe, March 5, 1872, reported that one worker left on his own, “not liking our climate,” while Sampson sent one back as “intractable.” The article also noted, “their dexterity, their diligence, their earnestness---“ and that their rooms were scrupulously clean. “In the dining room one of their number keeps an exact record of their expenses written upon the wall in Chinese characters, where it can be examined by each member. The weekly expense for each person for food, &c., is about two dollars and a quarter.”

So, the monthly expense for each Chinese worker was about $8.50, which might be only about one-third of their monthly wage, allowing them to save a good amount of their wages.

The article continued, “Outside the factory all have entire freedom.” They were not barred from any business in North Adams. Even those locals who had originally opposed the idea of hiring the Chinese workers, had little negative to say about the Chinese and offered no hindrance to them. In addition, “No death has occurred since the party arrived here, nor has there been a serious case of sickness.” Finally, the Chinese workers were asked if they planned to return home once their contract term was over. However, they were reticent to commit to a decision.

There was a brief mention in the Springfield Republican, April 4, 1872, that Sampson was dangerously ill, although his disease wasn’t specified and there wasn’t any follow-up information in the newspaper. There wasn’t any information on how it might have affected the shoe factory.

Fortunately, Sampson seemed to improve relatively quickly. The Boston Semi-Weekly Advertiser, April 30, 1872, discussed the Bureau of Statistics of Labor and their visit to the shoe factory. “The bureau thought itself treated rather hardly on the occasion of the visit to Mr. Sampson’s show factory at North Adams.” They had visited the prior year as well, and Sampson had once again refused to provide them any information about his Chinese workers, stating he would only do so if compelled by the law. However, he did make a concession and agreed to fill out a form with some information and mail it to the Bureau.

Sadly, the Boston Globe, August 30, 1872, reported that Quain Tung Tuck, 20 years old and one of the Chinese workers, died of rheumatism of the heart. This was the first death among the Chinese shoe workers.

More Chinese workers arrived! First, the Pittsfield Sun, September 4, 1872, mentioned that the original contract with the Chinese workers would end its term in June 1873. Then, it was thought they would all return home and other Chinese workers would arrive to replace them. However, the Boston Globe, November 28, 1872, reported that 30 more Chinese workers had arrived at the shoe factory two days ago, making the total 103.

A valuable gift! The Congregationalist, January 9, 1873, noted that Sampson had gifted Charles Sing, the foreman of the Chinese workers, a watch and gold chain that was worth $200 (about $5,000 in today’s dollars). The article stated, “They call it a testimonial of esteem.”

And even more Chinese workers. The Berkshire County Eagle, January 23, 1873, stated that 22 additional Chinese workers had arrived by railway, making it a total of 113 workers, although that total might be a mistake. There were 103 Chinese workers two months before, and no indication that ten, or even one, had left the factory during those two months.

However, the arrival of these new Chinese workers was marred by an act of racism. As they walked to the shoe factory, one young woman said to them, “Would oo like a little rat-tee?” This was the only reported incident at that time.

The article also mentioned that Sampson had added an addition to the factory building so that the workers would Chinese have better quarters. The new apartments were divided into several rooms, each with from 6-12 bunks. They were all well ventilated and warmed by steam, and there were wash rooms with hot and cold water.

Unfortunately, another Chinese worker died. The New England Farmer, February 22, 1873, reported that one of the workers died of pneumonia after being ill for 2 months. His name was not provided.

The Chinese workers were apparently very happy about their work as the Boston Globe, May 23, 1873, noted that Sampson had extended his contract with all but 6 of the original Chinese workers. So, nearly all of the original Chinese workers remained at the factory after the initial three year period ended in June. However, despite their general happiness about their work, there was a brewing discontent, which apparently had nothing to do with Sampson.

Their ire was directed at one of their own, their foreman, Charley Sing. The Berkshire County Eagle, August 21, 1873, reported, “For a long time past there has been a growing feeling of dissatisfaction among the Chinese laborers at Sampson’s shoe manufactory against ‘Charley Sing,’ the interpreter and overseer.” The article continued, “They claim that he has carried on a system of fraud against them from their first arrival in this town, charging them a large percentage on all that he purchases for them in the way of supplies—as, for instance, a quantity of rice which cost $50 he would charge them $75 or $100 for, and many small articles double the cost to him. He has charged fifty cents for mailing letters which already had the requisite stamps upon them. This deception they discovered and stopped.”

Three days ago, this came to such a row that Sampson called the state constable, requesting he come to preserve order. However, the Chinese quickly resolved the issues, albeit temporarily, and were back to work the next day.

The Boston Evening Transcript, October 29, 1873, noted that the dissension hadn’t been fully resolved yet, and some of the Chinese weren’t working while others were threatening to leave. In addition, Sing’s life had been threatened. During the near riot conditions on Monday, one worker, Ah Mi, was severely injured with doubts of his recovery. However, there wasn't any mention of him after this time, so hopefully he recovered.

More problems! The Berkshire County Eagle, November 6, 1873, reported that the dissension had continued, and that there were about 125 Chinese workers at the factory. One of the troublesome workers, Ah Coon, had been arrested. Unfortunately, some citizens raided the police station and assaulted the worker. Ah Coon was later fined $5 and costs, totaling $19.95. The money was paid and he left North Adams.

Sampson also let eight of the most problematic workers go, and brought in fifteen additional Chinese workers. At this same time, three Chinese men from New Jersey were at North Adams, accompanied by Oong Ar Showe, a famous Boston tea merchant. These men were attempting to mediate the matter, and Sing presented his accounts so they could be audited. The matter seems to have been resolved as it wasn’t raised again in any of the newspapers.

It was also noted that the workers were able to save about $12-$15 a month, roughly half their wages, after expenses and some had saved $400-$500 during the past 3 years.

Sadly, the Boston Globe, February 13, 1874, reported that one of the Chinese workers, who wasn’t identified, attempted to cut his own throat and it was thought that he probably wouldn’t survive. However, he apparently survived as he wasn't noted afterwards as a deceased worker.

It was now over four years since the arrival of the first Chinese workers to North Adams. The Boston Evening Transcript, July 15, 1874, noted that 21 Chinese workers had left the factory, returning to San Francisco, with plans to return to China. These were some of the original workers, and their fourth year had expired on July 1. They didn’t have any problems at the factory, but simply felt they needed to return home. Only 71 Chinese workers remained at the factory.

Another death. The Springfield Republican, July 24, 1874, reported that Hing Wing Shing, aged 20, had died from dropsy. He was buried in the same cemetery lot where the prior two workers were buried.

Bringing the band back! The Springfield Republican, August 28, 1874, noted that the Chinese workers had been practicing with their musical instruments, eight drums and a gong, which had been imported from China by Charlie Sing. It was said that Chung Hawk Ling was their best musician.

The Pittsfield Sun, October 14, 1874, briefly mentioned that 40 more Chinese workers were coming from San Francisco to the shoe factory. That would bring the total to 111.

A lengthy article about boot and shoe making in Massachusetts was published in the Springfield Republican, January 20, 1875. It was said that Massachusetts factories supplied great quantities of shoes to the army during the Revolutionary War, but afterwards, imports significantly hurt the industry. The industry rebounded though, and by 1845, the value of shoe production in the state was almost fifteen million dollars.

In 1870, the value has increased to about eighty-six million dollars, consisting of forty-five million pairs of shoes and ten million boots. In that year, there were about 1123 shoe & boot factories in Massachusetts, employing about 51,000 employees, whose aggregate wages were about twenty-five million dollars.

One of the most important technological innovations in shoe making was the wooden-peg. The article stated, “The wooden-peg, which has been largely instrumental in cheapening the cost of boots and shoes, is also a Massachusetts invention, having been devised by Joseph Walker of Hopkington, in about the year 1818.”

The article also devoted some attention to a history of the order of the Knights of St. Crispin. The order was first established in Glasgow, Scotland, early in the 19th century. Its original purpose was not antagonistic to capital, but to mutually protect both the employer and employees. It was then noted that the first Crispin lodge in the U.S. was established in 1866, which was quickly met with favor and other lodges sprouted up across the country. In Massachusetts, the largest lodge was in Lynn, with about 1400 members.

However, within the Crispins, there was a group of members considered to be “refractory spirits, who took every possible opportunity of claiming grievances, and strikes and other disturbances followed,..” The article also said, “It is claimed by the better class of Crispins that a majority of their troubles were caused by the foreign element, led on by a few hot-heads who were a discredit to the order.”

There was then a brief discussion of C.T. Sampson having trouble with the Crispins for about two years. After he asked for a temporary 10% reduction in their wages, the Crispins walked out and Sampson soon after he hired Chinese workers to replace the recalcitrant union workers.

Later that year, the Boston Globe, September 17, 1875, discussed the shoe factory, noting that 200 people currently worked at the shoe factory, with 93 being Chinese. By this point, almost all of the original 75 Chinese had left, for San Francisco or China. Over the course of about 28 months, those original workers had saved about $37,000.

Unfortunately, another Chinese worker died. The New England Farmer, February 22, 1873, reported that one of the workers died of pneumonia after being ill for 2 months. His name was not provided.

The Chinese workers were apparently very happy about their work as the Boston Globe, May 23, 1873, noted that Sampson had extended his contract with all but 6 of the original Chinese workers. So, nearly all of the original Chinese workers remained at the factory after the initial three year period ended in June. However, despite their general happiness about their work, there was a brewing discontent, which apparently had nothing to do with Sampson.

Their ire was directed at one of their own, their foreman, Charley Sing. The Berkshire County Eagle, August 21, 1873, reported, “For a long time past there has been a growing feeling of dissatisfaction among the Chinese laborers at Sampson’s shoe manufactory against ‘Charley Sing,’ the interpreter and overseer.” The article continued, “They claim that he has carried on a system of fraud against them from their first arrival in this town, charging them a large percentage on all that he purchases for them in the way of supplies—as, for instance, a quantity of rice which cost $50 he would charge them $75 or $100 for, and many small articles double the cost to him. He has charged fifty cents for mailing letters which already had the requisite stamps upon them. This deception they discovered and stopped.”

Three days ago, this came to such a row that Sampson called the state constable, requesting he come to preserve order. However, the Chinese quickly resolved the issues, albeit temporarily, and were back to work the next day.

The Boston Evening Transcript, October 29, 1873, noted that the dissension hadn’t been fully resolved yet, and some of the Chinese weren’t working while others were threatening to leave. In addition, Sing’s life had been threatened. During the near riot conditions on Monday, one worker, Ah Mi, was severely injured with doubts of his recovery. However, there wasn't any mention of him after this time, so hopefully he recovered.

More problems! The Berkshire County Eagle, November 6, 1873, reported that the dissension had continued, and that there were about 125 Chinese workers at the factory. One of the troublesome workers, Ah Coon, had been arrested. Unfortunately, some citizens raided the police station and assaulted the worker. Ah Coon was later fined $5 and costs, totaling $19.95. The money was paid and he left North Adams.

Sampson also let eight of the most problematic workers go, and brought in fifteen additional Chinese workers. At this same time, three Chinese men from New Jersey were at North Adams, accompanied by Oong Ar Showe, a famous Boston tea merchant. These men were attempting to mediate the matter, and Sing presented his accounts so they could be audited. The matter seems to have been resolved as it wasn’t raised again in any of the newspapers.

It was also noted that the workers were able to save about $12-$15 a month, roughly half their wages, after expenses and some had saved $400-$500 during the past 3 years.

Sadly, the Boston Globe, February 13, 1874, reported that one of the Chinese workers, who wasn’t identified, attempted to cut his own throat and it was thought that he probably wouldn’t survive. However, he apparently survived as he wasn't noted afterwards as a deceased worker.

It was now over four years since the arrival of the first Chinese workers to North Adams. The Boston Evening Transcript, July 15, 1874, noted that 21 Chinese workers had left the factory, returning to San Francisco, with plans to return to China. These were some of the original workers, and their fourth year had expired on July 1. They didn’t have any problems at the factory, but simply felt they needed to return home. Only 71 Chinese workers remained at the factory.

Another death. The Springfield Republican, July 24, 1874, reported that Hing Wing Shing, aged 20, had died from dropsy. He was buried in the same cemetery lot where the prior two workers were buried.

Bringing the band back! The Springfield Republican, August 28, 1874, noted that the Chinese workers had been practicing with their musical instruments, eight drums and a gong, which had been imported from China by Charlie Sing. It was said that Chung Hawk Ling was their best musician.

The Pittsfield Sun, October 14, 1874, briefly mentioned that 40 more Chinese workers were coming from San Francisco to the shoe factory. That would bring the total to 111.

A lengthy article about boot and shoe making in Massachusetts was published in the Springfield Republican, January 20, 1875. It was said that Massachusetts factories supplied great quantities of shoes to the army during the Revolutionary War, but afterwards, imports significantly hurt the industry. The industry rebounded though, and by 1845, the value of shoe production in the state was almost fifteen million dollars.

In 1870, the value has increased to about eighty-six million dollars, consisting of forty-five million pairs of shoes and ten million boots. In that year, there were about 1123 shoe & boot factories in Massachusetts, employing about 51,000 employees, whose aggregate wages were about twenty-five million dollars.

One of the most important technological innovations in shoe making was the wooden-peg. The article stated, “The wooden-peg, which has been largely instrumental in cheapening the cost of boots and shoes, is also a Massachusetts invention, having been devised by Joseph Walker of Hopkington, in about the year 1818.”

The article also devoted some attention to a history of the order of the Knights of St. Crispin. The order was first established in Glasgow, Scotland, early in the 19th century. Its original purpose was not antagonistic to capital, but to mutually protect both the employer and employees. It was then noted that the first Crispin lodge in the U.S. was established in 1866, which was quickly met with favor and other lodges sprouted up across the country. In Massachusetts, the largest lodge was in Lynn, with about 1400 members.

However, within the Crispins, there was a group of members considered to be “refractory spirits, who took every possible opportunity of claiming grievances, and strikes and other disturbances followed,..” The article also said, “It is claimed by the better class of Crispins that a majority of their troubles were caused by the foreign element, led on by a few hot-heads who were a discredit to the order.”

There was then a brief discussion of C.T. Sampson having trouble with the Crispins for about two years. After he asked for a temporary 10% reduction in their wages, the Crispins walked out and Sampson soon after he hired Chinese workers to replace the recalcitrant union workers.

Later that year, the Boston Globe, September 17, 1875, discussed the shoe factory, noting that 200 people currently worked at the shoe factory, with 93 being Chinese. By this point, almost all of the original 75 Chinese had left, for San Francisco or China. Over the course of about 28 months, those original workers had saved about $37,000.

Additional Chinese workers were hired through the agency of Yung, Chung, Wing & Co. of San Francisco. The Chinese were allegedly paid $26 a month, and it only cost them about $9 a month to live. The article also mentioned, “After working hours they are allowed the freedom of the town like other workmen, but they are never complained of for any breach of orders or manners, and in the shop they are quiet, peaceable and harmless.”

The Boston Post, September 17, 1875, repeated much of the information from the Globe article, but also added that the factory turned out about 23 cases (1380 pairs) of shoes each day. And the Daily Evening Traveller, September 17, 1875, added that the factory did an annual business of $500,000 (nearly $14 Million in today’s dollars).

The Springfield Republican, November 10, 1875, reported that the shoe factory was starting up again after running very low for a few weeks. This was because Sampson had been very sick for a month or so, and was slowly recovering.

Chinese New Year! The Boston Evening Transcript, January 26, 1876, mentioned that the Chinese workers had celebrated Chinese New Year yesterday with firecrackers, games and feasting. The writer noted that, “In their playing, as in everything else, their behavior is like that of large children.”

Financial troubles in North Adams. The Boston Post, June 12, 1876, alleged that all of the Chinese workers might be sent back to San Francisco as North Adams was suffering serious economic issues. The factory currently had 85 Chinese workers, with 40 having arrived a year ago. Of the workers, 40 were no longer bound by any contract but they had chosen to stay anyway.

The Boston Post, September 17, 1875, repeated much of the information from the Globe article, but also added that the factory turned out about 23 cases (1380 pairs) of shoes each day. And the Daily Evening Traveller, September 17, 1875, added that the factory did an annual business of $500,000 (nearly $14 Million in today’s dollars).

The Springfield Republican, November 10, 1875, reported that the shoe factory was starting up again after running very low for a few weeks. This was because Sampson had been very sick for a month or so, and was slowly recovering.

Chinese New Year! The Boston Evening Transcript, January 26, 1876, mentioned that the Chinese workers had celebrated Chinese New Year yesterday with firecrackers, games and feasting. The writer noted that, “In their playing, as in everything else, their behavior is like that of large children.”

Financial troubles in North Adams. The Boston Post, June 12, 1876, alleged that all of the Chinese workers might be sent back to San Francisco as North Adams was suffering serious economic issues. The factory currently had 85 Chinese workers, with 40 having arrived a year ago. Of the workers, 40 were no longer bound by any contract but they had chosen to stay anyway.

The article also commented that it was good that the arrival of the Chinese workers had eventually helped to largely break up the local order of the Crispins. However, no other shoe factory in North Adams had ever hired Chinese workers.

The Boston Globe, June 12, 1876, added some additional information, alleging that Sampson wouldn’t be rehiring any of the Chinese, “preferring to give employment to other residents of the town, who are suffering severely from the stoppage of several mills and workshops.” It was also noted that some of the prior Chinese workers had returned to China, and then came back to the U.S., where they now worked in Belleville, New Jersey, likely for the Passaic Steam Laundry.

It was also stated that the wages of these Chinese workers had never actually been known to the public but were thought to be around $20-$25 a month.

However, a little over two weeks later, the Boston Globe, June 30, 1876, had to report that their prior story that Sampson would let the Chinese workers return home was false. Those workers would continue to work at the shoe factory.

The Berkshire County Eagle, October 5, 1876, noted that four of the Chinese workers were recently baptized in the Baptist church. Their foreman, Charley Sing, had joined the same church some time ago.

Sing votes Republican! The Springfield Republican, October 13, 1876, reported that Charley Sing was the first Chinese person in the area who was permitted to vote, and Sing voted for the Republican platform. The Boston Globe, November 15, 1876, also noted that Charley Sing had recently been naturalized, making him eligible to vote.

It’s intriguing that the Chinese workers weren’t the only Chinese in North Adams at this time. There were at least two young Chinese boys studying at a local school. The North Adams Transcript, October 14, 1925, discussed the Veazie St. School, which had opened in North Adams in 1873, and which was now being closed. It was mentioned that in 1876, two of the students in the second grade were from China. They hadn’t spoken any English when they had first arrived in North Adams, but by the end of the year, they were said to be good students.

These two boys were connected to the Chinese workers at the shoe factory. They were the nephews of Charley Sing! Chung Toy, another worker, was Charley's brother and it's possible that these were Chung's sons. Unfortunately, no other details were provided so it’s unknown how or why the children came to North Adams. Did C.T. Sampson help bring them to North Adams?

Apparently eleven of the Chinese workers returned to San Francisco. The Pittsfield Sun, January 17, 1877, mentioned that there were now 74 Chinese workers at the shoe factory. It was also stated that Sampson was going to spend the rest of the winter in California.

Some basic information on the local shoe industry. The Pittsfield Sun, June 6, 1877, provided some statistics on the shoe business in North Adams, indicating that Sampson’s factory turned out about 7,000 cases of shoes each year, and had 235 employees. Millar & Whitman turned out 3,000 cases of shoes, with 100 employees, and Cady Brothers turned out 2500 cases, with 60 employees. Sampson clearly had the largest and most productive show factory in the region.

More Chinese workers left. The Fall River Daily Evening News, August 25, 1877, noted that there were now 65 Chinese workers at Sampson’s factory, nine less than in January. It was also mentioned that the factory was in its busiest season, producing 1600-1800 pairs of shoes each day. Interestingly, Ah Guy, one of the original 75 Chinese workers, had returned to China two years ago. He recently returned to the U.S. and asked Sampson if he could have his job back at the shoe factory, and Sampson hired him.

Another false rumor. The Fall River Daily Herald, October 13, 1877, alleged that Sampson had suspended work at his factory for an indefinite period and that the Chinese workers were going to all return home. The Boston Globe, October 23, 1877, noted that Sampson wasn’t going to discharge the Chinese workers as he was satisfied with their work. The factory had been closed for a short time, but was reopened in the latter half of November.

There was little information about the shoe factory provided by the newspapers in 1878. However, a later newspaper noted that, early in 1878, Charley Sing had established a grocery and tea store on Main Street in North Adams. It appears he was no longer working at the shoe factory.

The Boston Globe, June 12, 1876, added some additional information, alleging that Sampson wouldn’t be rehiring any of the Chinese, “preferring to give employment to other residents of the town, who are suffering severely from the stoppage of several mills and workshops.” It was also noted that some of the prior Chinese workers had returned to China, and then came back to the U.S., where they now worked in Belleville, New Jersey, likely for the Passaic Steam Laundry.

It was also stated that the wages of these Chinese workers had never actually been known to the public but were thought to be around $20-$25 a month.

However, a little over two weeks later, the Boston Globe, June 30, 1876, had to report that their prior story that Sampson would let the Chinese workers return home was false. Those workers would continue to work at the shoe factory.

The Berkshire County Eagle, October 5, 1876, noted that four of the Chinese workers were recently baptized in the Baptist church. Their foreman, Charley Sing, had joined the same church some time ago.

Sing votes Republican! The Springfield Republican, October 13, 1876, reported that Charley Sing was the first Chinese person in the area who was permitted to vote, and Sing voted for the Republican platform. The Boston Globe, November 15, 1876, also noted that Charley Sing had recently been naturalized, making him eligible to vote.

It’s intriguing that the Chinese workers weren’t the only Chinese in North Adams at this time. There were at least two young Chinese boys studying at a local school. The North Adams Transcript, October 14, 1925, discussed the Veazie St. School, which had opened in North Adams in 1873, and which was now being closed. It was mentioned that in 1876, two of the students in the second grade were from China. They hadn’t spoken any English when they had first arrived in North Adams, but by the end of the year, they were said to be good students.

These two boys were connected to the Chinese workers at the shoe factory. They were the nephews of Charley Sing! Chung Toy, another worker, was Charley's brother and it's possible that these were Chung's sons. Unfortunately, no other details were provided so it’s unknown how or why the children came to North Adams. Did C.T. Sampson help bring them to North Adams?

Apparently eleven of the Chinese workers returned to San Francisco. The Pittsfield Sun, January 17, 1877, mentioned that there were now 74 Chinese workers at the shoe factory. It was also stated that Sampson was going to spend the rest of the winter in California.

Some basic information on the local shoe industry. The Pittsfield Sun, June 6, 1877, provided some statistics on the shoe business in North Adams, indicating that Sampson’s factory turned out about 7,000 cases of shoes each year, and had 235 employees. Millar & Whitman turned out 3,000 cases of shoes, with 100 employees, and Cady Brothers turned out 2500 cases, with 60 employees. Sampson clearly had the largest and most productive show factory in the region.

More Chinese workers left. The Fall River Daily Evening News, August 25, 1877, noted that there were now 65 Chinese workers at Sampson’s factory, nine less than in January. It was also mentioned that the factory was in its busiest season, producing 1600-1800 pairs of shoes each day. Interestingly, Ah Guy, one of the original 75 Chinese workers, had returned to China two years ago. He recently returned to the U.S. and asked Sampson if he could have his job back at the shoe factory, and Sampson hired him.

Another false rumor. The Fall River Daily Herald, October 13, 1877, alleged that Sampson had suspended work at his factory for an indefinite period and that the Chinese workers were going to all return home. The Boston Globe, October 23, 1877, noted that Sampson wasn’t going to discharge the Chinese workers as he was satisfied with their work. The factory had been closed for a short time, but was reopened in the latter half of November.

There was little information about the shoe factory provided by the newspapers in 1878. However, a later newspaper noted that, early in 1878, Charley Sing had established a grocery and tea store on Main Street in North Adams. It appears he was no longer working at the shoe factory.

The Commercial Bulletin, July 20, 1878, reported that seven Chinese workers left for San Francisco, with plans to head to China. There were then only 40 Chinese workers left at the factory. Curiously, it was also noted that Charley Sing went to Virginia for a few days as he had an interest in a gold mine there.

Charley Sing got married! The Boston Post, August 2, 1878, reported that Sing had married Ida Kilburn of Morrissville, Virginia on July 23 in Virginia. The Cincinnati Daily Star (OH), August 10, 1878, noted that Ida was “A handsome, petite and wealthy girl…” The News Journal (DE), September 3, 1878, noted Ida was the “handsomest girl in North Adams” while the Baraboo Republic (WI), September 4, 1978, noted she was “one of the prettiest girls in the place.”

Charley Sing got married! The Boston Post, August 2, 1878, reported that Sing had married Ida Kilburn of Morrissville, Virginia on July 23 in Virginia. The Cincinnati Daily Star (OH), August 10, 1878, noted that Ida was “A handsome, petite and wealthy girl…” The News Journal (DE), September 3, 1878, noted Ida was the “handsomest girl in North Adams” while the Baraboo Republic (WI), September 4, 1978, noted she was “one of the prettiest girls in the place.”

It wasn't mentioned when Charley and Ida had first met, but it seems it might have occurred on Charley's visits to Virginia when he was taking care of his gold mine investment. Ida moved to North Adams with Charley.

It was noted in the Commercial Bulletin, August 31, 1878, that the shoe factory was currently producing about 30 cases per day of women’s and children’s shoes.

As January 1879 arrived, Sampson made some changes to his factory’s business status. The Boston Evening Transcript, January 2, 1879, stated the Sampson Shoe Factory had now become a corporation, the C.T. Sampson Manufacturing Company. Sampson was the President and Treasurer of the corporation while George W. Chase was the Clerk.

Another Chinese worker died. The Boston Globe, February 4, 1879, discussed the death of John Thomas, another Chinese worker, who was 25 years old and a member of the Baptist church. He died of typhoid pneumonia and he was the sixth Chinese worker to die. His Chinese name was Ah Nam, and he was first hired about 6 years ago. He used to work the pegging machine. “Very few men can stand the strain upon their system caused by running this machine, and about a year ago John Thomas began to break down.”

Last spring, he had bleeding of the lungs, and for a week or two it was thought that he might die. Fortunately, he recovered and resumed his old work, sticking to it until about a month ago, when his lungs began to bleed again.

The Fall River Daily Herald, March 8, 1879, noted that Charley Sing's grocery store was "one of the most popular mercantile establishments in western Massachusetts.” It was also noted that Sing had purchased an interest in a southern gold mine, which didn’t work out, and it was thought he would take a loss of several thousand dollars. The article also noted that Sing had “married a very intelligent American lady, and they are at present keeping house in richly furnished apartments in the business centre of the town.”

The Pittsfield Sun, February 26, 1879, briefly noted that Chung Toy had bought the grocery store which Charley Sing had opened in North Adams. Chung Toy used to work at the shoe factory and he was the brother of Sing.

A battle at the shoe factory! The Boston Post, July 4, 1879, reported that there had been an altercation between the Chinese and white workers at Sampson’s factory. One of the Chinese workers struck Elmer Hewett, a pegger, and then Hewett “laid the Chinaman out with a single blow.” Other Chinese and white workers got involved in the fracas, and there was a brief fight, with tools and other items thrown. One white worker got a bad cut above his eye. The fight didn’t appear to be racially motivated.

The Cedar Falls Gazette, July 4, 1879, noted that Charley Sing and his wife had a daughter, named Birdie Burlingame Virginia Sing. The article also stated she was probably the first child born to a Chinese and white couple. However, The Recorder (FL), October 27, 1879, mentioned that his daughter’s name was Chung Burlingame Virginia Sing.

It was noted in the Commercial Bulletin, August 31, 1878, that the shoe factory was currently producing about 30 cases per day of women’s and children’s shoes.

As January 1879 arrived, Sampson made some changes to his factory’s business status. The Boston Evening Transcript, January 2, 1879, stated the Sampson Shoe Factory had now become a corporation, the C.T. Sampson Manufacturing Company. Sampson was the President and Treasurer of the corporation while George W. Chase was the Clerk.

Another Chinese worker died. The Boston Globe, February 4, 1879, discussed the death of John Thomas, another Chinese worker, who was 25 years old and a member of the Baptist church. He died of typhoid pneumonia and he was the sixth Chinese worker to die. His Chinese name was Ah Nam, and he was first hired about 6 years ago. He used to work the pegging machine. “Very few men can stand the strain upon their system caused by running this machine, and about a year ago John Thomas began to break down.”

Last spring, he had bleeding of the lungs, and for a week or two it was thought that he might die. Fortunately, he recovered and resumed his old work, sticking to it until about a month ago, when his lungs began to bleed again.

The Fall River Daily Herald, March 8, 1879, noted that Charley Sing's grocery store was "one of the most popular mercantile establishments in western Massachusetts.” It was also noted that Sing had purchased an interest in a southern gold mine, which didn’t work out, and it was thought he would take a loss of several thousand dollars. The article also noted that Sing had “married a very intelligent American lady, and they are at present keeping house in richly furnished apartments in the business centre of the town.”

The Pittsfield Sun, February 26, 1879, briefly noted that Chung Toy had bought the grocery store which Charley Sing had opened in North Adams. Chung Toy used to work at the shoe factory and he was the brother of Sing.