About a week ago, the

Fodor's Travel website posted an article,

The Ozark Town Where Cashew Chicken Was Invented by

Erika Ebsworth-Goold (August 12, 2024). The article stated, "

Springfield also has an unexpected culinary claim to fame. It’s the birthplace of a beloved takeout classic: cashew chicken." This referred to

Springfield, Missouri, and the article also noted, "

It turns out the creation was first cooked up more than six decades ago at a Springfield tea house." This was the tale of

David Leong, a Chinese immigrant, who owned

Leong's Tea House, which opened in 1963.

The problem is that this story is misleading, and doesn't accurately reflect the truth about the invention of cashew chicken. David Leong plays an important role in the history of cashew chicken, but it requires further explanation.

First, and importantly, cashew chicken is a traditional Chinese dish, sometimes referred to as

腰果鸡丁, (

Yāoguǒ jī). To the Chinese, cashews resemble the golden ingots that once were used as a form of currency, so they are consumed during the Chinese New Year, hoping for prosperity for the New Year. However, the traditonal dish is commonly stir-fried in a wok, using small pieces of chicken, with vegetables and roasted cashews, in a light sauce. David Leong clearly didn't invent this dish. So, what did he invent?

The earliest reference I found in the U.S. for "cashew chicken" was in the

Chula Vista Star (CA), May 28, 1948. The above advertisement indicated that Dock's served American and Chinese cuisine, and one of their dishes included “

Cashew Chicken" for $1.50.

A few years later, the first recipe appeared in an ad in

The Independent, January 25, 1951. The Food Bowl Market offered a recipe for “

Chicken-Cashew Nut.”

However, apparently not all chicken cashew dishes had a Chinese origin. For example,

The Patriot News (PA), October 7, 1951, published an article on amateur poultry cooks in Pennsylvania It stated, “

Pennsylvania Dutch dishes stopped the poultry show last week in Harrisburg as spectators gazed in wonderment while 28 farm women and two men put together ingredients for tempting poultry and egg dishes.” One of those dishes included “

chicken cashew.”

Another example, with a recipe, was included in the

Buffalo News (NY), December 11, 1951. There was clearly no Chinese influence in this recipe.

Another non-Chinese influenced recipe was found in

The Grand Island Independent (NE), August 21, 1952. This recipe was also printed in newspapers in California, Florida and Wisconsin.

In the Complete Chicken Cookery (1953) by Marian Tracy, there was another recipe, for a dish that wasn't Chinese inspired.

The Merced Sun-Star (CA), March 3, 1955, published an advertisement for

The Grange Company, noting “

Better Feed for California Chickens.” The ad also mentioned, “

Sometime in the last 4,000 years a Chinese genius sampled his latest culinary experiment and delightedly announced “This is it!” A recipe for "

Chicken with Pineapple and Cashew Nuts." This is the first recipe where the chicken was fried in a batter, and coated with crushed cashew nuts. The recipe is also very different from the traditional Chinese version.

The fact the chicken in this recipe was fried in a batter is important as over 11 years later, David Leong would become famous for frying his chicken pieces in his cashew chicken dish. It doesn't seem likely that David would have seen this recipe as he was living in Missouri at the time, and probably wouldn't have been reading California newspapers.

As for Chinese versions of cashew chicken, the Ogden Standard-Examiner (UT), March 8, 1956, briefly mentioned Yu Tou Guy Ding (diced chicken with cashew nuts). In the Daily Palo Alto Times (CA), September 24, 1956, there was an ad from Ming's, a Cantonese restaurant. It mentioned a Typical Family Dinner for Four, and one of the dishes was “Cashew Chicken.” The Honolulu Star-Bulletin (HI), February 23, 1957, also had a restaurant ad, for Mok Larn Chein restaurant, with a large menu and one of the items was “Cashew nut chicken” for $1.50.

The Chicago Tribune (IL), November 18, 1957, published a recipe for Chicken Cashew, a "$5 Favorite Recipe" from one of their readers. This recipe obviously was inspired by Chinese recipes.

The Stockton Evening and Sunday Record (CA), May 9, 1958, ran an ad for

Minnie’s, which offered Chinese-American dishes, including “

Cashew Chicken Mandarin.”

The Journal Herald (OH), September 26, 1958, in a discussion of Chinese restaurants in San Francisco, briefly mentioned "

cashew chicken."

More details came in

The Peninsula Times Tribune (CA), February 25, 1959. The newspaper provide a recipe for a Cantonese dish, cashew chicken, which came from

Ming restaurant's chef

Mee Wah Jung. The article also noted, “

The cashew chicken (‘yew dow gai kow’) is cubes of boned chicken, marinated and toss-cooked with crisp cashews from India, onions and bamboo shoots.” This was basically a more traditional version of the dish.

The Independent (CA), March 27, 1959, had an ad for

New China Tea Garden, offering “

Cashew Nut Chicken Chow Yuke” for $1.55.

The Daily Illini (IL), June 3, 1959, also had an ad for the new

Hong Kong Restaurant, with a specialty of Cashew Chicken.

The Anaheim Gazette (CA), February 12, 1960, mentioned the

Crow’s Restaurant in

Long Beach, a Chinese-American restaurant, which served “

Cashew Nut Chicken.” During the next couple years, cashew chicken would be mentioned in a number of other ads for Chinese-American restaurants, and there would be other traditional recipes provided as well.

The Douglas County Gazette (NE), October 12, 1962, offered an interesting recipe variation called "

Cashew Chicken Casserole."

Eight Immortal Flavors (1963), a Chinese cookbook, by

Johnny Kan &

Charles L. Leong, contained a recipe for "

Cashew Chicken (Yew Dow Gai Kow)," which was similar to their Walnut Chicken recipe, but with cashews instead of walnuts. This was again, a very traditional recipe.

And it's also in 1963, that the tale of a new version of Cashew Chicken began, although the origins of that tale extend back over twenty years. Many sources claim that David Leong invented cashew chicken in 1963, but in actuality, he only invented a fried variation of it. And the actual year of that invention is in question.

************

Around 1940, David Leong, a native of China, immigrated to the United States and soon became a naturalized citizen. During World War II, he was drafted and served during the invasion of Normandy. After the war, David started working in restaurants on the East Coast and in the South, including in New Orleans, Florida, and New York.

In 1955, David was working at a Chinese restaurant in Florida. There are two different versions of what happened next, although the end result was the same. The Springfield Leader and Press (MO), May 1, 1977, stated that Dr. John L.K. Tsang, a physician in Springfield, Missouri, desired Chinese cuisine in Springfield so he advertised in a Chinese newspaper nationwide. David Leong read the advertisement and persuaded Gee, his brother, to move with him to Springfield, to work in a restaurant and serve Chinese cuisine.

However, six years later, the Springfield Leader and Press (MO), September 21, 1983, provided a different version of this event. The article claimed that in 1955, Dr. Tsang visited Pensacola, Florida and patronized the restaurant where David worked. Dr. Tsang was so impressed with the food that he convinced David, and his brother, to return to Springfield with him and work in a restaurant there. Whichever version is true, the end result was the same, with David and Gee Leong moving to Missouri to work in a restaurant preparing Chinese cuisine.

The Springfield News-Leader (MO), August 24, 1955, reported that the Lotus Garden restaurant would open that week, offering Chinese and American cuisine. The restaurant was owned by Dr. Tsang, who was said to have employed “a Chinese born-chef who served with the U.S. Army in combat action on the European fronts during World War II.” Neither David Leong or his brother Gee were mentioned by name in the article, although this would be the first restaurant in Springfield they worked in.

The Springfield Leader and Press (MO), January 14, 1956, presented an ad for Lotus Garden, which listed some of their Chinese dishes, from egg rolls to chicken chow mein.

It seems Dr. Tsang soon after sold the restaurant to Win Yin Leong, who didn't seem related to David Leong. David continued to work at the Lotus Gardens into 1957, although he would move to another restaurant early in 1958.

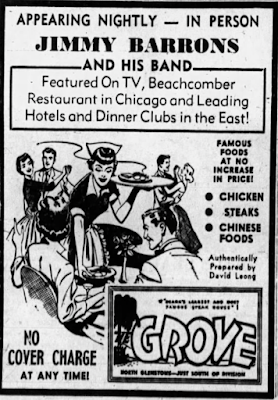

The

Springfield Leader and Press (MO), April 14, 1958, presented the above advertisement for

The Grove, a supper club, where the food was “

authentically prepared by David Leong.” David appears to have been the primary chef rather than his brother Gee, as Gee was not mentioned in connection with either Lotus Garden or The Grove.

A terrible accident! The Springfield Leader and Press (MO), August 7, 1960, reported that a vehicle, a 1960 Pontiac, struck The Grove restaurant. The damage was significant, creating an 8 foot wide and 5 foot high hole in one of the restaurant walls and also causing a minor gas explosion. The vehicle also pinned two cooks, David Leong, age 39, and Yuen Leong, age 28 (this might actually be Gee), to a wall. Both of them sustained second and third degree burns and were taken to the hospital, although they were quickly treated and then released, so the injuries may not have been as significant as they seemed. The vehicle also caused about $10,000 in property damages, which included about $2,000 in dishes.

A few years later, David and Gee decided to establish their own restaurant. The Springfield Leader and Press (MO), May 12, 1963, reported that David and Gee had plans in the works to open a new Chinese-American restaurant in Springfield. The newspaper noted, “Two Chinese brothers, both cooks, and both already well-known in the Ozarks and nationwide for their original Chinese dishes, will be the owners and operators of the establishment.”

The new restaurant,

Leong's Tea House was supposed to open in mid-November, 1963, but an explosion changed those plans. The

Springfield Leader and Press (MO), November 18, 1963, reported that someone placed about 10 sticks of dynamite next to a wall of the soon-to-open restaurant. The above photograph shows some of the results of the explosion. The

Springfield News-Leader (MO), November 19, 1963, added more information. The property damages were estimated at $2000-$2500, and the building owner, Lee McLean, offered a $1500 reward for information on the bombers. The police believed the dynamite was placed or thrown, maybe in a metal container, at the base of a 8-foot square plastic window. The Leongs had not received any prior threats, and the police didn't have any suspects. Curiously, the two 75-pound stone lions, which were in the front of the restaurant, had also been stolen that same night.

Arrests made! The

Springfield Leader and Press (MO), December 5, 1963, stated that three men had been arrested for “

grand stealing” for the theft of the 2 stone lions. The men included

Walter Lewis Phillips., III (age 23),

Dennis Earl Nelson (age 20), and

Ralph Warren Crover (age 37). The three men, pictured above, are posing with the stone lions and certainly don’t look remorseful.

More information came from the Springfield News-Leader (MO), December 5, 1963. Dennis, a delivery man, and Walter, who designed costume jewelry, admitted to stealing the stone lions. The police then followed up and arrested Ralph, a cosmetologist. However, results of lie detector tests cleared them of any connection to the bombing. It seemed that the theft was merely a strange coincidence. The Springfield Leader and Press (MO), January 13, 1964, then reported that the three defendants pled guilty to new charges of malicious destruction of property and were fined $25 plus costs.

It didn't appear that the identify of the bomber or bombers was ever solved, and there weren't any other similar incidents.

The

Springfield Leader and Press (MO), December 8, 1963, mentioned that Leong’s Tea House had just opened and the above photo shows the exterior of the restaurant.

The

Springfield News-Leader (MO), January 1, 1964, printed the first advertisement for

Leong’s Tea House, but it didn't mention cashew chicken. Another ad in the

Springfield Leader and Press (MO), January 5, 1964, mentioned that they served Special Sunday dinners including

Southern Fried Chicken, and also offered “

Delicious Chinese Foods.” Additional advertisements in 1964 for the restaurant continued to mention Southern Fried Chicken, and only a single Chinese dish: "

Chow Steaks, Kew." That dish was described as "

Sliced Beef Tenderloin With Chinese Vegetables and Pea Pod Mushrooms."

The first mention of cashew chicken at the restaurant was in July 1965, about a year and a half after its opening. The Springfield Leader and Press (MO), July 13, 1965, mentioned that a wedding party was held at Leong’s and they had a menu of cashew chicken and rice. Did David serve cashew chicken when his restaurant first opened in December 1963? And if he did, was it the traditional version? When did David first serve his own variation, where the chicken was battered and fried? It doesn't appear there is any documentary evidence to answer all of these questions.

There is some information that Leong's Tea House might not have done well at the start, as the populace wasn't too willing to embrace Chinese cuisine. Allegedly, that is when David decided to create some Chinese dishes that appealed more to American tastes. Their Southern Fried Chicken might have been a big seller, so David may have then decided to alter the traditional cashew chicken dish and fried the chicken rather than stir-fry it. So, David's version of cashew chicken might not have been invented until 1964, 1965, or even later.

The next mention of cashew chicken wouldn't be for another year, when the Springfield Leader and Press (MO), July 28, 1966, noted that another wedding party had a luncheon at Leong and their menu included cashew chicken. The Springfield Leader and Press (MO), September 9, 1966, also mentioned a luncheon meeting with a menu including “cashew chicken.” The Polk County Times (MO), February 9, 1967, had a similar mention. None of these mentions indicated that the cashew chicken was of the fried chicken variation.

The

Springfield Leader and Press (MO), June 5, 1967, presented an ad for

The Grove restaurant which mentioned that one of their Chinese dinners included “

Cashew Chicken, Egg Foo Young, Steamed Rice” for $1.95. Was this the traditional dish, or had The Grove adopted David's fried chicken variation? Unfortunately, the ad doesn't provide an answer.

Another Springfield restaurant serving cashew chicken! The

Springfield Leader and Press (MO), October 31, 1971, noted that the House of Cheong, a Chinese American Restaurant, had recently opened by

Cheong Leong, who had 18 years of experiences in the Chinese restaurant business. Cashew chicken was one of their offerings, although again we don't know whether this was the traditional dish or not.

Leong's Tea House and David Leong received much attention in a lengthy newspaper article in May 1977, about 13 1/2 years after the restaurant's opening. The Springfield Leader and Press (MO), May 1, 1977, began by explaining that Springfield, Missouri had a population of about 146,000, and “has perhaps become the Chinese restaurant capital of the Midwest.” The article also added, “we’re guessing Springfield has more Chinese food outlets per capita” than other major cities.

The article then stated, “What may surprise many is that the cashew chicken dish served in nearly all of these restaurants originated in Springfield.” The article also explained the two types of cashes chicken. “True, it has a real Chinese counterpart, but the crusty chicken bits, served with rice and oyster sauce so familiar to Springfield diners is David Leong’s version of a steamed chicken dish served in Hong Kong.” David felt that “Americans won’t eat steamed fish or chicken” so he decided to fry it instead in his dish. The exact date of that invention wasn't specified.

The Springfield Leader and Press (MO), January 3, 1979, provided an article about Gee Leong, and included a recipe for Crispy Cashew Chicken, which would probably be similar to the dish they served at their restaurant.

The Springfield Leader and Press (MO), September 21, 1983, presented some confusing information. It began with, “About two decades ago, believe it or not, there was no cashew chicken. Not in Springfield. Not even in China.” This was clearly untrue, and the article even contradicted itself, stating, “And knowing the American palate to be fond of fried foods, Leong took a Cantonese steamed chicken dish and adapted it a bit. He dipped the boneless chicken chunks in a tempura-style batter, fried them, covered them with oyster sauce, chopped green onions and cashews, and served them on a bed of rice.” That statement indicated cashew chicken was a Cantonese dish, which David put his on spin on.

David's variation acquired its own identity. The Columbia Daily Tribune (MO), February 28, 1984, provided the first mention of “Springfield-Style Cashew Chicken,” which was an homage to David Leong. Over time, that name would spread across the country, so everyone understood what Springfield-Style meant.

The Springfield Leader and Press (MO), April 19, 1989, mentioned that there were about 350 restaurants in Springfield, considering all of the various cuisines, and that about 53 of those restaurants offered cashew chicken. The Daily Journal (MA), May 1, 1990, noted that Springfield had acquired the unofficial nickname of “Cashew Chicken Capital of the Midwest.” The article also noted that a local newspaper columnist had done some calculations, estimating that Springfield restaurants served at least 6697-8554 dishes of cashew chicken each day, averaging 2.4 -3.1 million a year. The article continued, “Chefs here dip the chicken in batter, deep-fat fry it, smother it with a thick brown sauce made from chicken stock and soy sauce, add cashews and a few bits of green onion and serve the concoction beside a bed of fried rice.”

David Leong may not have invented cashew chicken but his fried variation has achieved its own element of immortality, becoming extremely popular and spreading across the country. David's variation has existed for about 60 years and its popularity has probably never been greater. It's best to refer to his creation as “Springfield-Style Cashew Chicken,” to differentiate it from the classic version.

Do you prefer the traditional Cashew Chicken or the newer Springfield-style Cashew Chicken?