The British East India Company began importing tea from China in the latter half of the 17th century, though initially it was an expensive luxury. However, over the course of about thirty years, the price dropped until eventually it was cheap enough for everyone, spreading tea consumption throughout the country. In addition, as the 18th century began, the East India Company had garnered a monopoly in the British Empire of trading with China. Thus, no one from the American colonies were permitted to trade with China.

Tea was introduced into the American colonies during the mid-17th century. Around 1650, Peter Stuyvesant, the director-general of New Amsterdam (which would become New York), introduced tea to the colony, where it became extremely popular. By the end of the century, it’s said that more tea was being drunk there than in England. During the 18th century, tea spread throughout the colonies, becoming common for all social classes, and by the middle of the century, the average colonist was consuming at least one cup of tea per day.

In general, the colonies had to purchase their tea from British traders, although sometimes they bought it from smugglers. During the early 1770s, as tensions with Britain increasing and war came, it’s said that about 75%-95% of the tea drank by colonists was then smuggled into the country. Even with the Boston Tea Party and similar protests, colonists continued to drink plenty of tea, simply obtaining it elsewhere than from the British.

After the Revolutionary War, when the U.S. was no longer part of the British Empire, they were finally able to begin their own trade with China, and over time would sell to China ginseng, sea otter pelts, silver, sandalwood, sea cucumbers, cotton fabric, and other items. American ships sailed around the Cape of Good Hope on their way to China. U.S. received silks, porcelain, furniture, and hundreds of thousands of tons of tea.

The first American ship to engage in trade with China, traveling across the seas to the port of Canton, was the Empress of China, a former 360-ton privateer, in 1784. At this time, Canton was the only Chinese port open to Westerners, and it had first been visited by Europeans, the Portuguese, in 1516. The English didn’t begin visiting Canton until 1637.

As an aside, a ship from Boston should have actually been the first American merchant ship to sail to Canton. In 1783, the Harriet, a 55-ton sloop under the command of Captain Hallet, set sail for Canton with a full cargo of ginseng root. However, while passing around the Cape of Good Hope, they encountered a ship owned by the East India Company. Possibly to protect their trade with Canton, the British ship offered to buy their ginseng, for double its weight in Hyson tea. Hyson tea, also known as Lucky Dragon tea, is a Chinese green tea. Captain Hallet chose to accept this deal, turn his ship around and return to Massachusetts. Accepting this lucrative deal was obviously much less dangerous than continuing to sail to Canton.

However, the Empress of China still had a significant connection to Boston. Backed by Robert Morris, who previously provided financial support during the American Revolution, the objective of the mercantile journey of the Empress of China was to obtain Chinese tea. To trade with the Chinese, the vast majority of the cargo of the Empress was ginseng, about 30 tons.

According to The Old China Trade by Foster Rhea Dulles (1930), ginseng was “.., a root used by the Chinese for its supposed miraculous healing qualities. It grew wild both in Manchuria and in the forests of the New World.” In addition, ginseng was “Known as the ‘dose for immortality,’ it was worth its weight in gold.” The forests of the U.S., including New England, were searched for ginseng root, which was considered inferior to the native Chinese ginseng, but still garnered quite a high price.

Robert Morris chose Samuel Shaw, a Bostonian and Revolutionary War hero, to be the supercargo, essentially the man in charge of selling the cargo, of the Empress of China. This was a hugely important role, and the very success of the journey was dependent upon Shaw’s mercantile and negotiation skills.

Shaw, who was born in 1754, worked in counting houses prior to the Revolutionary War so was familiar with business. In 1775, when he was about 21 years old, Shaw joined the militia during the Siege of Boston, which lasted for nearly a year. He was promoted multiple times during the War, eventually ending up in 1780 as a Captain of the 3rd Artillery.

The Old China Trade by Foster Rhea Dulles (1930), stated Shaw was ”Shrewd, far-sighted, and of keen judgment, he was well equipped to deal with the merchants of Canton, but even more important, his tact and understanding were the qualities most necessary to win their friendship…” Shaw didn’t seem to possess any prejudices against the Chinese.

The Empress of China departed from New York on February 22, 1784, arriving in Canton on August 28. Shaw kept a journal of his experiences in Canton, concentrating primarily on the business aspects of his journey. He didn’t feel qualified enough to make general conclusions about the Chinese people as he saw only a very limited slice of their society, just a portion of their business aspect.

His journal also had an interesting passage which showed the nature of his soul and morality, and which was indicative that he was probably an excellent choice for the endeavor to Canton. During the sea voyage, Shaw passed by a French slave ship, and was outraged by what he saw, being a fierce opponent of slavery.

In The Journals of Major Samuel Shaw, the First American Consul at Canton by Samuel Shaw and Josiah Quincy (1847), Shaw wrote, “A number of the naked blacks were on deck,--poor creatures, going to a state of hopeless slavery, and, torn from every tender connection, doomed to eat the bread and drink the water of affliction for the reside of their miserable lives! Good God! And is it man, who distinguishing characteristic should be humanity and the exercise of every milder virtue, who wears sweet smiles and looks erect on heaven,--is it man, endowed by three with a capacity for enjoying happiness and suffering misery, to whom thou hast imparted a knowledge of thyself, enabled him to judge of right and wrong, and taught to believe in a state of future retribution,--it is man, who, thus tramping upon the principles of universal benevolence, and running counter to the very end of his creation, can become a fiend to torment his fellow-creatures, and deliberately effect the temporal misery of beings equally candidates with himself for a happy immortality.”

One matter he did mention was that the Chinese were initially confused about Americans, believing at first they were Englishmen. The Old China Trade by Foster Rhea Dulles (1930), it noted, “Among the Chinese the Americans were regarded as the ‘New People,’ and Shaw took great pains to explain the extent of the country from which he came and the possibilities of trade which his initial venture opened up.”

During his time in Canton, he was involved in a precarious situation which became known as the Canton War. A British ship, the Lady Hughes, had issued a gun salute in honor of some guests who had just dined on board. However, it accidentally killed a Chinese man and wounded two others on a ship located alongside the British vessel.

The Chinese demanded that the British turn over the gunner to them to face Chinese justice, which would have been a death sentence. The British refused, and two days later, the Chinese captured the supercargo of that British vessel, holding him hostage. They also suspended all trade and tensions were very high, with armed vessels on both sides gathering together, presenting an obvious threat.

In a letter printed in The Pennsylvania Packet & Daily Advertiser (PA), September 10, 1785, Shaw wrote, “It is a maxim of the Chinese law, that blood must answer for blood; in pursuance of which they demanded the unfortunate gunner. To give up the poor man was to consign him to certain death.” He also stated, “Humanity pleaded powerfully against the measure.” Obviously Shaw didn’t believe the gunner should be handed over to the Chinese.

As noted in The Old China Trade by Foster Rhea Dulles (1930), “Shaw now took the lead in urging a united front on the part of all concerned to force the Chinese to surrender their hostage and reach a peaceful solution of the controversy. But there was no feeling of unity among these rival traders. The French, the Danes and the Dutch frankly refused to risk hostilities on behalf of the English.” Despite their refusals, Shaw continued to support the British, even though their two countries had been at war recently.

Eventually, as there appeared no other viable option, the British surrendered, and turned their gunner over to the Chinese, who executed him by strangling. That action restored peace and commerce to Canton, albeit at a terrible price.

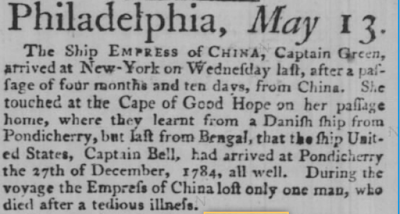

On December 28, 1784, Shaw sailed back home, having sold all of his cargo, acquiring 2460 piculs of black tea, 562 piculs of green tea, plus some silk, chinaware, and other assorted items. A picul is approximately 133 1/3 pounds, so the cargo included about 164 tons of black tea and 37.5 tons of green tea. The ship arrived back in New York on May 11, 1785. With a capital investment of $120,000, their profit was about 25%, or around $30,000.

The Empress of China planned to make a second voyage to Canton, and wanted Shaw to participate once again. Unfortunately, Shaw’s portion of the profits of the first journey hadn’t been significant so he had quickly acquired a new job, being appointed the First Secretary of the War Department. He decided not to accept the offer to rejoin the Empress.

However, China seemed to call to Shaw, and he soon resigned his position with the War Department to join a different ship travelling to Canton. In fact, five mercantile vessels (including one from Salem, Massachusetts) traveled to Canton within a year of the return of the Empress.

One of the other ships leaving New York was the Hope, and Shaw joined this voyage, leaving New York in February 1786, and arriving back in Canton in August. In 1786, Shaw was also appointed Consul to China by Congress, a position which would be renewed by President George Washington in 1790.

During this second voyage, Shaw found that nearly all of the tea prices in Canton were at least 25% higher than his prior voyage. In The Journals of Major Samuel Shaw, the First American Consul at Canton by Samuel Shaw and Josiah Quincy (1847), Shaw wrote, “The inhabitants of America must have tea,--the consumption of which will necessarily increase with the increasing population of our country.” Shaw remained in China until he sailed back to the U.S. in January 1789, finally reaching Newport, Rhode Island in July 1789.

The Old China Trade by Foster Rhea Dulles (1930), stated Shaw was ”Shrewd, far-sighted, and of keen judgment, he was well equipped to deal with the merchants of Canton, but even more important, his tact and understanding were the qualities most necessary to win their friendship…” Shaw didn’t seem to possess any prejudices against the Chinese.

The Empress of China departed from New York on February 22, 1784, arriving in Canton on August 28. Shaw kept a journal of his experiences in Canton, concentrating primarily on the business aspects of his journey. He didn’t feel qualified enough to make general conclusions about the Chinese people as he saw only a very limited slice of their society, just a portion of their business aspect.

His journal also had an interesting passage which showed the nature of his soul and morality, and which was indicative that he was probably an excellent choice for the endeavor to Canton. During the sea voyage, Shaw passed by a French slave ship, and was outraged by what he saw, being a fierce opponent of slavery.

In The Journals of Major Samuel Shaw, the First American Consul at Canton by Samuel Shaw and Josiah Quincy (1847), Shaw wrote, “A number of the naked blacks were on deck,--poor creatures, going to a state of hopeless slavery, and, torn from every tender connection, doomed to eat the bread and drink the water of affliction for the reside of their miserable lives! Good God! And is it man, who distinguishing characteristic should be humanity and the exercise of every milder virtue, who wears sweet smiles and looks erect on heaven,--is it man, endowed by three with a capacity for enjoying happiness and suffering misery, to whom thou hast imparted a knowledge of thyself, enabled him to judge of right and wrong, and taught to believe in a state of future retribution,--it is man, who, thus tramping upon the principles of universal benevolence, and running counter to the very end of his creation, can become a fiend to torment his fellow-creatures, and deliberately effect the temporal misery of beings equally candidates with himself for a happy immortality.”

One matter he did mention was that the Chinese were initially confused about Americans, believing at first they were Englishmen. The Old China Trade by Foster Rhea Dulles (1930), it noted, “Among the Chinese the Americans were regarded as the ‘New People,’ and Shaw took great pains to explain the extent of the country from which he came and the possibilities of trade which his initial venture opened up.”

During his time in Canton, he was involved in a precarious situation which became known as the Canton War. A British ship, the Lady Hughes, had issued a gun salute in honor of some guests who had just dined on board. However, it accidentally killed a Chinese man and wounded two others on a ship located alongside the British vessel.

The Chinese demanded that the British turn over the gunner to them to face Chinese justice, which would have been a death sentence. The British refused, and two days later, the Chinese captured the supercargo of that British vessel, holding him hostage. They also suspended all trade and tensions were very high, with armed vessels on both sides gathering together, presenting an obvious threat.

In a letter printed in The Pennsylvania Packet & Daily Advertiser (PA), September 10, 1785, Shaw wrote, “It is a maxim of the Chinese law, that blood must answer for blood; in pursuance of which they demanded the unfortunate gunner. To give up the poor man was to consign him to certain death.” He also stated, “Humanity pleaded powerfully against the measure.” Obviously Shaw didn’t believe the gunner should be handed over to the Chinese.

As noted in The Old China Trade by Foster Rhea Dulles (1930), “Shaw now took the lead in urging a united front on the part of all concerned to force the Chinese to surrender their hostage and reach a peaceful solution of the controversy. But there was no feeling of unity among these rival traders. The French, the Danes and the Dutch frankly refused to risk hostilities on behalf of the English.” Despite their refusals, Shaw continued to support the British, even though their two countries had been at war recently.

Eventually, as there appeared no other viable option, the British surrendered, and turned their gunner over to the Chinese, who executed him by strangling. That action restored peace and commerce to Canton, albeit at a terrible price.

On December 28, 1784, Shaw sailed back home, having sold all of his cargo, acquiring 2460 piculs of black tea, 562 piculs of green tea, plus some silk, chinaware, and other assorted items. A picul is approximately 133 1/3 pounds, so the cargo included about 164 tons of black tea and 37.5 tons of green tea. The ship arrived back in New York on May 11, 1785. With a capital investment of $120,000, their profit was about 25%, or around $30,000.

The Empress of China planned to make a second voyage to Canton, and wanted Shaw to participate once again. Unfortunately, Shaw’s portion of the profits of the first journey hadn’t been significant so he had quickly acquired a new job, being appointed the First Secretary of the War Department. He decided not to accept the offer to rejoin the Empress.

However, China seemed to call to Shaw, and he soon resigned his position with the War Department to join a different ship travelling to Canton. In fact, five mercantile vessels (including one from Salem, Massachusetts) traveled to Canton within a year of the return of the Empress.

One of the other ships leaving New York was the Hope, and Shaw joined this voyage, leaving New York in February 1786, and arriving back in Canton in August. In 1786, Shaw was also appointed Consul to China by Congress, a position which would be renewed by President George Washington in 1790.

During this second voyage, Shaw found that nearly all of the tea prices in Canton were at least 25% higher than his prior voyage. In The Journals of Major Samuel Shaw, the First American Consul at Canton by Samuel Shaw and Josiah Quincy (1847), Shaw wrote, “The inhabitants of America must have tea,--the consumption of which will necessarily increase with the increasing population of our country.” Shaw remained in China until he sailed back to the U.S. in January 1789, finally reaching Newport, Rhode Island in July 1789.

In addition, some statistics on this early China trade were provided by The Trouble with Tea by Jane T. Merritt (2017). “All told, between 1784 and 1790, forty-one American maritime ventures exchanged goods in Canton markets; some ships, such as the Empress of China, made several voyages. Over the next decade (1791–1800) another 166 American vessels sailed directly to China.” As for the tea trade, Merritt wrote, “Into the 1790s, tea made up at least half of the cargo value for most American ships trading in China.” In addition, “Whereas Samuel Wharton had reckoned that Americans drank 2 pounds of tea annually in the 1770s, a typical family of the 1790s might purchase and drink 4 to 5 pounds each year.”

While in Canton on this second voyage, Shaw had also commissioned a new ship to be built in Quincy, Massachusetts. It was to be the largest American ship, at 800 tons, ever launched and was named the Massachusetts. It was launched in September 1789 and Shaw underwent a voyage to Canton in March 1790, arriving in September. However, this trip encountered difficulties, and Shaw had trouble selling all of his cargo.

Curiously, Shaw decided to sell his new ship, and it was either bought by the Portuguese or the Danish (dependent on which source you consult). Shaw acknowledged that it was a very well built ship, but its size was more of a detriment than an asset. Such a large cargo posed a greater risk for investors and Shaw felt it was probably better to have smaller cargos, and thus less risk, attracting more potential investors.

He returned to the United States in 1792 but sailed again for China soon after, which would prove to be his final voyage. During this journey, he stopped Bombay, due to typhoons, where he contracted a serious liver disease. He reached Canton in November 1793, but, still ill, he chose to leave China in March 1794, but never reached the U.S. On May 30, near the Cape of Good Hope, Shaw succumbed to his illness and was buried at sea. Samuel Shaw was instrumental in establishing good relations with China, leading to a successful mercantile trade.

Over time, American merchants attempted to seek other trade items, besides ginseng, which would satisfy the Chinese, and this eventually led to a trade in sea otter fur pelts obtained from the Native Americans of the Northwest Coast. In September 1787, a group of six Boston merchants financed two ships, the Columbia and Lady Washington, to sail to the Northwest, obtain furs, and then travel to China.

The two ships encountered numerous difficulties on route, so that only the Columbia eventually made the journey to Canton. In August 1790, the ship successfully returned to Boston with 350 chests of Bohea tea, a black tea. Soon thereafter, other ships started buying furs to trade with China.

The Old China Trade by Foster Rhea Dulles (1930) stated: “Boston had initiated the trade; Boston kept a virtual monopoly of it.” For example, from 1790-1818, 108 U.S. vessels traveled to the Northwest and traded furs to China. There’s a partial list of these ships, with the names of 63 of them, and of that group, 52 were from Boston. That definitely shows Boston had a near monopoly on that trade.

How important was the China trade to the U.S.? According to When America First Met China: An Exotic History of Tea, Drugs, and Money in the Age of Sail, by Eric Jay Dolin, “The China trade was critical to the growth and success of the new nation. It bolstered America’s emerging economy, enabling Boston, New York, Philadelphia, Salem, Providence, and other ports to thrive after the ravages of the war. In doing so it helped create the nation’s first millionaires, instilled confidence in Americans in their ability to compete on the world’s stage, and spurred an explosion in shipbuilding that led to the construction of the ultimate sailing vessels—the graceful and exceedingly fast clipper ships.”

Who would have thought that the trade in Chinese tea could end up being so important to the future of the U.S.?

No comments:

Post a Comment