Slade’s Bar & Grill (once known as Slade’s Barbecue) is an institution in Roxbury, and it has existed for over 90 years, introducing North Carolina barbecue to Boston. A recent Boston Globe article, by Devra First, about Slade’s Bar & Grill intrigued me, and I strongly encourage you to read that article first and then return to this one.

I decided to delve deeper into the history of this pioneering restaurant, which was founded by Renner Slade. During my research, I leaned even more fascinating information about Slade's Barbecue, including that it is even older than it claims.

The Renner-Slade company was incorporated in Delaware by Renner Slade, Daisy Mae Slade, and Henry Brown. Renner acted as the President and General Manager. They produced about 15 different types of soaps, including Laundry Soap, Toilet Soap, Liquid Soap and Shampoo, Automobile Soap, Paint Cleaning Soap, and Soap Powders.

As an aside, it appeared Daisy Mae worked at least part-time as a writer. She penned an article in the St. Louis Clarion (MO), April 2, 1921, about a speech given by Col. Roscoe Conkling Simmons at the Uniontown High School. Simmons was a journalist and orator, currently working for The Chicago Defender, a black weekly newspaper. He was also the nephew of Booker T. Washington.

The Boston Globe, November 13, 1934, reported that Renner Slade purchased real estate at 21 Hollander Street, in the Elm Hill section of Roxbury. The estate included a frame house and 3300 square feet of land, which was assessed at $8500.

As of March 1935, Renner Slade owned three barbecue restaurants, and he was already being referred to as the “Barbecue King.” Renner’s second restaurant, located across the street from his spot on 958 Tremont, was intended to handle the crowds that couldn’t fit into his main restaurant. Renner then decided to open a third spot on Columbus Avenue. At this time, Renner employed about 100 people, nearly all who were black. In 1936, Slade apparently established a Slade’s Barbecue at 217 Neck Street, North Weymouth..

The Tribune Independent (MI), March 23, 1935, stated Renner had a record of selling 60,000 barbecued chicken dinners.

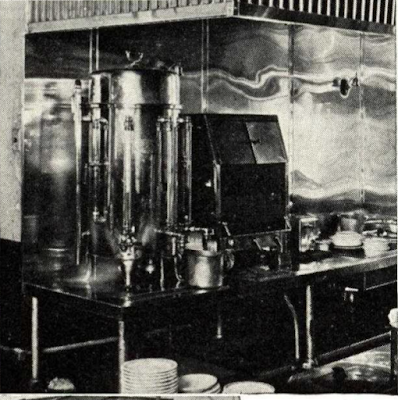

In a 1938 catalog by Republic Steel, there was information about food service equipment by Enduro, which possessed a metallic, silvery lustre. Enduro equipment was used in Slade’s Barbecue, including for a steam table, hood over the steam table, urn stand table top, and back paneling (which is pictured above).

Slade’s Barbecue saw even more growth during the next four years, but it would become a case of too much, too soon. The Pittsburgh Courier (PA), December 16, 1939, mentioned that Renner opened a fourth restaurant, a more deluxe spot in the Back Bay. Plus, Renner acquired a chicken ranch in Abington, which possessed modern AC equipment and had a capacity for 25,000 chickens. Each week, this farm produced about 4500 4-pound broilers for his restaurants! He also acquired a “truck farm,” adjacent to the chicken farm, which produced vegetables for his restaurant.

As an aside, the Boston Traveler, December 9, 1959, reported that Slade had been mentioned in a Ripley’s Believe It Or Not column for being a restaurant owner competing against himself, owning four restaurants, which all served essentially the same food.

Slade admitted in the Pittsburgh Courier (PA), December 16, 1939, that he had expanded too rapidly, which led him to selling nearly everything but his main restaurant on Tremont. At that remaining restaurant, he employed over 50 people, including 4 bartenders and 7 chefs. Selling his other properties turned out to be profitable, as Renner now claimed that his main restaurant made a greater profit than he had seen from all four of his restaurants before.

Even though Slade’s website states the restaurant began in 1935, there are a number of sources that indicate the restaurant actually started in 1928, seven years earlier. However, the roots of the restaurant also allegedly extend back a few generations to North Carolina, to the great-grandfather of Renner Slade.

According to folklore, the origins of Slade’s Barbecue were spawned in pre-Civil War North Carolina. The Boston Traveler, December 9, 1959, related the story that the enslaved Benjamin Slade chose to celebrate his 41st birthday by preparing a “gigantic barbecue for himself and his friends in a secluded glade in the woods near where he lived.” This gathering was apparently a secret, meant to be hidden from the slave owners.

According to folklore, the origins of Slade’s Barbecue were spawned in pre-Civil War North Carolina. The Boston Traveler, December 9, 1959, related the story that the enslaved Benjamin Slade chose to celebrate his 41st birthday by preparing a “gigantic barbecue for himself and his friends in a secluded glade in the woods near where he lived.” This gathering was apparently a secret, meant to be hidden from the slave owners.

The article continued, “The food was what he and his friends could collect, and Benjamin served it with a special seasoning of herbs he had gathered.” However, they were discovered at their barbecue by a group which probably included the owner of Benjamin. Rather than punish Benjamin, it was said that his barbecue food was so impressive that Benjamin was relieved of his duties as a general worker and made a cook. He would then prepare barbecue for numerous social and political gatherings.

The Greensboro Daily News (NC), January 20, 1960, also added that, “Part of the folklore is that Slade had been a slave and won his independence because of the gratitude his master had for many wonderful barbecue feasts.” The Boston Traveler article didn't allege that Slade had been freed due to his culinary skills.

Both the Boston Traveler, March 23, 1956, and the News and Observer (NC), January 31, 1960, mentioned that Benjamin Slade was the great-grandfather of Renner Slade, who would found Slade’s Barbecue Restaurant. Those articles also claimed that Benjamin had first introduced barbecue to North Carolina (a claim which many dispute).

Benjamin’s cooking secrets were said to have been passed down through his family, and many of those recipes have remained unchanged throughout the generations. According to the Boston Herald, August 20, 1945, both the grandfather and father of Renner Slade operated barbecue restaurants in North Carolina. However, I haven't been able to otherwise confirm the veracity of this claim and no other source made this claim.

Renner Slade was born around 1881 and the Pittsburgh Courier (PA), December 16, 1939, claimed that “Mr. Slade’s desire to be a chef and his own boss, started ‘way back when he was a child and saw a man in a white cap making hot cakes in a restaurant window.” Slade thought about that image all his life, wanting to be like this cook, but he wanted to produce meat rather than hot cakes. This would seem to refute that his father and grandfather operated barbecue restaurants, as you would have expected Renner's inspiration to have derived from those restaurants.

A different origin tale was related in the Boston Traveler, December 9, 1959. First, it indicated that Renner had been taught to cook by his sister. Second, it claimed that as a young boy, a number of people in his home town, including family members, died of “black draught” which Renner thought was malnutrition, and that better nutrition might have saved them.

The Greensboro Daily News (NC), January 20, 1960, also added that, “Part of the folklore is that Slade had been a slave and won his independence because of the gratitude his master had for many wonderful barbecue feasts.” The Boston Traveler article didn't allege that Slade had been freed due to his culinary skills.

Both the Boston Traveler, March 23, 1956, and the News and Observer (NC), January 31, 1960, mentioned that Benjamin Slade was the great-grandfather of Renner Slade, who would found Slade’s Barbecue Restaurant. Those articles also claimed that Benjamin had first introduced barbecue to North Carolina (a claim which many dispute).

Benjamin’s cooking secrets were said to have been passed down through his family, and many of those recipes have remained unchanged throughout the generations. According to the Boston Herald, August 20, 1945, both the grandfather and father of Renner Slade operated barbecue restaurants in North Carolina. However, I haven't been able to otherwise confirm the veracity of this claim and no other source made this claim.

Renner Slade was born around 1881 and the Pittsburgh Courier (PA), December 16, 1939, claimed that “Mr. Slade’s desire to be a chef and his own boss, started ‘way back when he was a child and saw a man in a white cap making hot cakes in a restaurant window.” Slade thought about that image all his life, wanting to be like this cook, but he wanted to produce meat rather than hot cakes. This would seem to refute that his father and grandfather operated barbecue restaurants, as you would have expected Renner's inspiration to have derived from those restaurants.

A different origin tale was related in the Boston Traveler, December 9, 1959. First, it indicated that Renner had been taught to cook by his sister. Second, it claimed that as a young boy, a number of people in his home town, including family members, died of “black draught” which Renner thought was malnutrition, and that better nutrition might have saved them.

It was also alleged that Renner had worked in hotels and restaurants throughout the country, which would have been prior to his soap business days. However, this was the only reference to indicate Renner had worked as a cook prior to when he came to Boston.

The confusion likely resulted because there was another Renner Slade during this time period, who also was a black chef, and started working in resorts and restaurants in New York. In 1928, this Slade eventually moved to Pennsylvania, taking a job at the Central Hotel in Hanover, PA, and his wife also worked there as a pastry chef.

The earliest documented reference I found to Renner Slade was in the Connellsville Daily Courier (PA), November 14, 1907, in a wedding notice. On November 12, Renner Slade of Connellsville married Daisie Mae Young, and they planned to reside at 234 Main Street in Connellsville.

The next references to Renner would not be until 1920 and 1921, detailing his establishment of the Renner-Slade Soap & Chemical Co. in Pennsylvania. At some point before 1920, Renner had moved from North Carolina to Uniontown, PA. Why did Renner, if he had worked in various restaurants, decide to shift gears so drastically to run a soap business? I wasn't able to find any information about why Renner decided to establish this soap business.

The earliest documented reference I found to Renner Slade was in the Connellsville Daily Courier (PA), November 14, 1907, in a wedding notice. On November 12, Renner Slade of Connellsville married Daisie Mae Young, and they planned to reside at 234 Main Street in Connellsville.

The next references to Renner would not be until 1920 and 1921, detailing his establishment of the Renner-Slade Soap & Chemical Co. in Pennsylvania. At some point before 1920, Renner had moved from North Carolina to Uniontown, PA. Why did Renner, if he had worked in various restaurants, decide to shift gears so drastically to run a soap business? I wasn't able to find any information about why Renner decided to establish this soap business.

The Renner-Slade company was incorporated in Delaware by Renner Slade, Daisy Mae Slade, and Henry Brown. Renner acted as the President and General Manager. They produced about 15 different types of soaps, including Laundry Soap, Toilet Soap, Liquid Soap and Shampoo, Automobile Soap, Paint Cleaning Soap, and Soap Powders.

As an aside, it appeared Daisy Mae worked at least part-time as a writer. She penned an article in the St. Louis Clarion (MO), April 2, 1921, about a speech given by Col. Roscoe Conkling Simmons at the Uniontown High School. Simmons was a journalist and orator, currently working for The Chicago Defender, a black weekly newspaper. He was also the nephew of Booker T. Washington.

The subject of his speech, was Under Which Flag, which Daisy Mae stated was the “finest address ever heard in our city.” The speech included a eulogy of Abraham Lincoln and Booker T. Washington. Plus, while Simmons was in the city, he was a guest at the Slade's home.

Renner-Slade Soap ran into some serious legal problems in 1924. The Daily Courier (PA), August 8, 1924, reported on a judgment in a lawsuit against Renner-Slade Soap Co., and their property and factory on Feathers Avenue, Uniontown, was seized and taken. Despite this serious setback, it appears Slade continued, at least on a partial basis, in the business.

The Uniontown Morning Herald (PA), April 1, 1925, published an advertisement for “Slade’s Magic Cleanser” which was said to be “Absolutely harmless on the best painted walls, pictures, enameled woodwork, tile or brick." Interested parties were asked to contact Renner Slade at Box 1202, Uniontown, PA. Was he just selling off prior products? Or was he producing them at another location?

The Boston Traveler, December 9, 1959, claimed that a fire destroyed his soap business but no other reference confirmed this claim. The lawsuit, which seized his factory, was obviously a significant factor in the downfall of the soap business.

Within the next few years, Renner Slade decided to get out of the soap business, and moved from Pennsylvania to Boston, MA in 1928. In addition, at some point before 1928, Renner’s marriage to Daisie Mae ended, and he remarried a woman named Anna Burnette. I’ll also note that they eventually had two daughters, Donessa (born August 27, 1934) and Anne (born around 1937).

It was in 1928, not 1935, that Renner Slade opened his first barbecue restaurant. The Boston Traveler, December 9, 1959, mentioned that when Renner Slade first came to Boston, in 1928, barbecue was largely unknown in this region. So, with a starting capital of $700, Slade opened a barbecue restaurant. “His first restaurant was on the first floor of a building on Warwick St., Roxbury, around the corner from the present location.” Renner would cook chickens in the window, leaving it open so the aroma would entice people. The restaurant only had two tables, and some customers would stand outside or sit on the sidewalk to enjoy their barbecue.

In addition, the Pittsburgh Courier (PA), December 16, 1939, indicated that Slade, and his wife, opened their first restaurant at a small location on Hammond Street, in Roxbury, which could seat about 20 people. Warwick intersects Hammond, so his first restaurant was likely at this intersection. Within two months, “Boston discovered him and barbecue chicken became the fad.”

Soon enough, to expand, they tore down a wall to the house next door, and then could seat 100 people. And about nine months later, they moved to a spot on the corner of Hammond and Tremont Streets, at 958 Tremont, where the restaurant has stood ever since.

There was a brief mention in the Wyandotte Echo (KS), August 19, 1932, of a dinner held at Slade’s Barbecue on Tremont Street.

The Uniontown Morning Herald (PA), April 1, 1925, published an advertisement for “Slade’s Magic Cleanser” which was said to be “Absolutely harmless on the best painted walls, pictures, enameled woodwork, tile or brick." Interested parties were asked to contact Renner Slade at Box 1202, Uniontown, PA. Was he just selling off prior products? Or was he producing them at another location?

The Boston Traveler, December 9, 1959, claimed that a fire destroyed his soap business but no other reference confirmed this claim. The lawsuit, which seized his factory, was obviously a significant factor in the downfall of the soap business.

Within the next few years, Renner Slade decided to get out of the soap business, and moved from Pennsylvania to Boston, MA in 1928. In addition, at some point before 1928, Renner’s marriage to Daisie Mae ended, and he remarried a woman named Anna Burnette. I’ll also note that they eventually had two daughters, Donessa (born August 27, 1934) and Anne (born around 1937).

It was in 1928, not 1935, that Renner Slade opened his first barbecue restaurant. The Boston Traveler, December 9, 1959, mentioned that when Renner Slade first came to Boston, in 1928, barbecue was largely unknown in this region. So, with a starting capital of $700, Slade opened a barbecue restaurant. “His first restaurant was on the first floor of a building on Warwick St., Roxbury, around the corner from the present location.” Renner would cook chickens in the window, leaving it open so the aroma would entice people. The restaurant only had two tables, and some customers would stand outside or sit on the sidewalk to enjoy their barbecue.

In addition, the Pittsburgh Courier (PA), December 16, 1939, indicated that Slade, and his wife, opened their first restaurant at a small location on Hammond Street, in Roxbury, which could seat about 20 people. Warwick intersects Hammond, so his first restaurant was likely at this intersection. Within two months, “Boston discovered him and barbecue chicken became the fad.”

Soon enough, to expand, they tore down a wall to the house next door, and then could seat 100 people. And about nine months later, they moved to a spot on the corner of Hammond and Tremont Streets, at 958 Tremont, where the restaurant has stood ever since.

There was a brief mention in the Wyandotte Echo (KS), August 19, 1932, of a dinner held at Slade’s Barbecue on Tremont Street.

The Boston Herald, June 24, 1933, printed an ad for Slade’s Barbecue, stating; “Delicious food at a moderate price. Our coffee is freshly brewed every few minutes.” The restaurant was also said to be open nightly until 2:30 am

The Boston Globe, November 13, 1934, reported that Renner Slade purchased real estate at 21 Hollander Street, in the Elm Hill section of Roxbury. The estate included a frame house and 3300 square feet of land, which was assessed at $8500.

As of March 1935, Renner Slade owned three barbecue restaurants, and he was already being referred to as the “Barbecue King.” Renner’s second restaurant, located across the street from his spot on 958 Tremont, was intended to handle the crowds that couldn’t fit into his main restaurant. Renner then decided to open a third spot on Columbus Avenue. At this time, Renner employed about 100 people, nearly all who were black. In 1936, Slade apparently established a Slade’s Barbecue at 217 Neck Street, North Weymouth..

The Tribune Independent (MI), March 23, 1935, stated Renner had a record of selling 60,000 barbecued chicken dinners.

Interestingly, around 1935, Renner’s clientele was 80% white, and that percentage only grew, so that by 1940, the clientele was said to be 98% white. This likely didn’t change significantly until the 1950s and 1960s, when the black population in Roxbury experienced a great boom in growth. In the Pittsburgh Courier (PA), December 16, 1939, an article alleged, “Residents of Roxbury give Slade credit for starting to bring large numbers of white patrons to this section to eat and spend their money where it would help his race. Nearly all of Slade's employees were black.

When Prohibition ended in December 1933, Renner Slade began applying for liquor licenses, at least as far back as November 1935, and maybe earlier.

When Prohibition ended in December 1933, Renner Slade began applying for liquor licenses, at least as far back as November 1935, and maybe earlier.

In a 1938 catalog by Republic Steel, there was information about food service equipment by Enduro, which possessed a metallic, silvery lustre. Enduro equipment was used in Slade’s Barbecue, including for a steam table, hood over the steam table, urn stand table top, and back paneling (which is pictured above).

Slade’s Barbecue saw even more growth during the next four years, but it would become a case of too much, too soon. The Pittsburgh Courier (PA), December 16, 1939, mentioned that Renner opened a fourth restaurant, a more deluxe spot in the Back Bay. Plus, Renner acquired a chicken ranch in Abington, which possessed modern AC equipment and had a capacity for 25,000 chickens. Each week, this farm produced about 4500 4-pound broilers for his restaurants! He also acquired a “truck farm,” adjacent to the chicken farm, which produced vegetables for his restaurant.

As an aside, the Boston Traveler, December 9, 1959, reported that Slade had been mentioned in a Ripley’s Believe It Or Not column for being a restaurant owner competing against himself, owning four restaurants, which all served essentially the same food.

Slade admitted in the Pittsburgh Courier (PA), December 16, 1939, that he had expanded too rapidly, which led him to selling nearly everything but his main restaurant on Tremont. At that remaining restaurant, he employed over 50 people, including 4 bartenders and 7 chefs. Selling his other properties turned out to be profitable, as Renner now claimed that his main restaurant made a greater profit than he had seen from all four of his restaurants before.

Slade said, “...that it was Boston’s cosmopolitan air and its appreciation of good cooking that built his success in a business that is worth one half million dollars today.” In today's dollars, that would equate to about 9.6 Million. Quite a successful business.

Renner also stated that he knew 80% of his patrons by name, especially as he often spent time sitting and chatting with them at the restaurant. Besides the restaurant, Renner still did some catering, including some large-scale events. At a 20th anniversary celebration in Vermont, he barbecued two steers, weighing 1700 pounds, and 12 lambs. For a century celebration in Connellsville, PA, Renner served about 10,000 people, delivering “every known variety of barbecued meats.”

The Boston Traveler, December 9, 1959, also referenced the Vermont barbecue, held in Morrisville, but stated it was an ox-roast, maybe the first in modern history in the area. About 5,000 people sat through a drizzling rain to enjoy the two oxen.

The Pittsburgh Courier (PA), December 16, 1939, continued in their article and mentioned some of the other employees of Slade’s Barbecue, such as Conwell Florence, the general manager and Slade’s right hand man. Elwyn Barrows was a “Well known organist and pianist takes care of the entertainment nightly at the café.” And Thomas Brown was the “courteous head waiter.”

Renner Slade was called “Boston’s King of Barbecue,” famous for his barbecue chicken and meats, which were flavored with a special sauce. The article concluded that Slade’s Barbecue was “A living monument to a genius who discovered what people liked to eat…and gave it to them.”

A brief ad in the Boston Herald, January 21, 1943.

The Wellesley News, April 8, 1944, printed the above ad, noted it had existed since 1928.

Unfortunately, Renner Slade, age 64, passed away in August 1945, but the restaurant would stay in the Slade family for a time, eventually becoming owned by Donessa Slade, Renner’s daughter, and managed by her husband, Earl Coblyn.

During the second half of the 1950s, there were several brief mentions of Slade's Barbecue. The Boston Traveler, March 23, 1956, mentioned that it still “presents barbecue at its best.” A writer in the Boston American, March 2, 1958, mentioned that he was surprised to learn that the jukebox at Slade’s Barbecue had an old hit from 1939, Bill Kenny’s Ink Spots “If I Didn’t Care.” Many other jukeboxes during this period contained only the most recent hits, so it was unusual to find a jukebox with a twenty-year old hit.

A brief mention in the Boston American, December 27, 1959, stated that Slade’s Barbecue was celebrating their 31st anniversary, which is again evidence that the restaurant opened in 1928. There was a small ad in the Boston American, January 19, 1960, noting Slade’s Barbecue sold “Mouth-Watering Chicken” and was open from 9am-3am.

The Greensboro Daily News (NC), January 20, 1960, in referencing Slade’s Barbecue, wrote that “For patrician Boston knows the delights of Eastern North Carolina barbecue. The pleasure has been Boston’s for five generations or more.” It also wrote, “Slade’s restaurant, 958 Tremont Street, Boston, has that indefinable something which characterizes Goldsboro barbecue.” High praise from a bastion of barbecue.

A curious coincidence? The Boston Daily Record, December 14, 1960, discussed a new Western television show, Shotgun Slade. Slade’s grandfather was Benjamin Slade, the successful owner of a chicken barbecue restaurant. However, Slade (no first name every provided) wasn’t interested in working at the restaurant, so he ended up as a private detective. Did the creators of his western derive inspiration from the story of Slade’s Barbecue, Renner Slade, and his ancestor, Benjamin Slade?

We'll end with an amusing and cute story. The Boston American, April 3, 1961, reported on a story about Chickie, a 3-month old cat, owned by Amy Robertson, the 7 year old daughter of Irving Robertson, a co-owner of Slade’s Barbecue.

Renner also stated that he knew 80% of his patrons by name, especially as he often spent time sitting and chatting with them at the restaurant. Besides the restaurant, Renner still did some catering, including some large-scale events. At a 20th anniversary celebration in Vermont, he barbecued two steers, weighing 1700 pounds, and 12 lambs. For a century celebration in Connellsville, PA, Renner served about 10,000 people, delivering “every known variety of barbecued meats.”

The Boston Traveler, December 9, 1959, also referenced the Vermont barbecue, held in Morrisville, but stated it was an ox-roast, maybe the first in modern history in the area. About 5,000 people sat through a drizzling rain to enjoy the two oxen.

The Pittsburgh Courier (PA), December 16, 1939, continued in their article and mentioned some of the other employees of Slade’s Barbecue, such as Conwell Florence, the general manager and Slade’s right hand man. Elwyn Barrows was a “Well known organist and pianist takes care of the entertainment nightly at the café.” And Thomas Brown was the “courteous head waiter.”

Renner Slade was called “Boston’s King of Barbecue,” famous for his barbecue chicken and meats, which were flavored with a special sauce. The article concluded that Slade’s Barbecue was “A living monument to a genius who discovered what people liked to eat…and gave it to them.”

A brief ad in the Boston Herald, January 21, 1943.

The Wellesley News, April 8, 1944, printed the above ad, noted it had existed since 1928.

Unfortunately, Renner Slade, age 64, passed away in August 1945, but the restaurant would stay in the Slade family for a time, eventually becoming owned by Donessa Slade, Renner’s daughter, and managed by her husband, Earl Coblyn.

During the second half of the 1950s, there were several brief mentions of Slade's Barbecue. The Boston Traveler, March 23, 1956, mentioned that it still “presents barbecue at its best.” A writer in the Boston American, March 2, 1958, mentioned that he was surprised to learn that the jukebox at Slade’s Barbecue had an old hit from 1939, Bill Kenny’s Ink Spots “If I Didn’t Care.” Many other jukeboxes during this period contained only the most recent hits, so it was unusual to find a jukebox with a twenty-year old hit.

A brief mention in the Boston American, December 27, 1959, stated that Slade’s Barbecue was celebrating their 31st anniversary, which is again evidence that the restaurant opened in 1928. There was a small ad in the Boston American, January 19, 1960, noting Slade’s Barbecue sold “Mouth-Watering Chicken” and was open from 9am-3am.

The Greensboro Daily News (NC), January 20, 1960, in referencing Slade’s Barbecue, wrote that “For patrician Boston knows the delights of Eastern North Carolina barbecue. The pleasure has been Boston’s for five generations or more.” It also wrote, “Slade’s restaurant, 958 Tremont Street, Boston, has that indefinable something which characterizes Goldsboro barbecue.” High praise from a bastion of barbecue.

A curious coincidence? The Boston Daily Record, December 14, 1960, discussed a new Western television show, Shotgun Slade. Slade’s grandfather was Benjamin Slade, the successful owner of a chicken barbecue restaurant. However, Slade (no first name every provided) wasn’t interested in working at the restaurant, so he ended up as a private detective. Did the creators of his western derive inspiration from the story of Slade’s Barbecue, Renner Slade, and his ancestor, Benjamin Slade?

We'll end with an amusing and cute story. The Boston American, April 3, 1961, reported on a story about Chickie, a 3-month old cat, owned by Amy Robertson, the 7 year old daughter of Irving Robertson, a co-owner of Slade’s Barbecue.

One day, a vending machine service man loaded up the cigarette dispenser at Slade’s, and somehow Chickie snuck into the dispenser. During the next two days, people could hear cat cries but no one could locate the source. When Irving went to get a pack of cigarettes, he heard the kitten inside and realized what had happened. The kitten, unharmed, was safely removed from the machine.

Slade's Barbecue, now Slade’s Bar & Grill, has a fascinating history, although more in-depth research might be able to uncover even more details. I'll end by returning to a compelling quote from the Pittsburgh Courier (PA), December 16, 1939, “A living monument to a genius who discovered what people liked to eat…and gave it to them.”

1 comment:

While attending Boston University, in 1958-9, some classmates and I would go to the Boston Garden on a Sunday. Get cheap seats, for about a$1, watch the Celtics and then watch as the wooden floor would be taken up so that we would then see a Bruins game. After the hockey game ended, we would head over to Slades Barbeque for the greatest food bargain in Boston. For $1.50, or so, we would have a 1/4 of a chicken, potatoes, veggies, and a drink. After eating at Slades, we would then go further up on Tremont St., to a bar that would be showing war movies on a big screen. We would each pitch in a buck or to buy a couple of pitchers of beer and enjoy 1 or 2 of the movies for that night. What memories!

Post a Comment