Within two years of the establishment of Boston’s Chinatown, there may have been a Chinese herbal doctor in the community. Some of the earliest newspaper references to Chinese herbal doctors failed to provide the name of the doctors, as well as other identifying information. However, the importance of such herbalists was very evident, and such herbalists are still vital to the Chinatown community today.

The first newspaper reference to a Chinese herbalist was provided in the

Boston Globe, August 16, 1889. The writer sought the only Chinese doctor in Boston, to question him about the “

elixir of life,” a discovery credited to

Dr. Brown Sequard, a Mauritian who taught at Harvard for a few years during the 1860s. This elixir would allegedly prolong life, and numerous doctors were experimenting with it, to assess whether it was effective or not. Some claimed that the Chinese had known of this elixir for many years before its alleged discovery by Dr. Sequard.

The Chinese doctor was difficult to locate, but was finally found in a top story apartment at 38 ½ Harrison Avenue. His office, a narrow little room with bunks, was in the front of the apartment, and one wall of the room was lined with shelves containing “.

.curious-looking bottles containing different-colored mixtures.” In the rear of the room, on the bunks, were Chinese under the influence of opium.

Fortunately, the herbalist spoke English so the writer didn’t required a translator. The writer asked the doctor if he “

...had occasion to use a medicine which is subcutaneously injected into the blood, and which has the capacity of prolonging human life or will give the muscles and nerves increased force…”

The herbalist answered affirmatively, and from one of the shelves took down a box that contained a little package that appeared wrapped in the skin of a lizard. The writer wrote, “

This he explained contained a powder that not only would make a man live long, but when its soul departed from its earthly abode it would ensure him a reserved seat in the happy land on the other side of the river.” He continued, “

The doctor explained that the powder was dropped on a cut made in the left arm, and it generally killed three out of four who tried it, but those who survived the test would be made aware of its powerful influences as an elixir."

Would you take such an elixir, if it provided extreme longevity, but also killed 75% of the people who took it?

The herbalist also showed the writer a different mixture which “

…would add 10 years to an ordinary life. It was composed of certain matter taken from the bodies of lizards, worms and various insects, and two drops were considered a dose.” This mixture apparently didn't kill anyone who took it. There is certainly a question as to whether the herbalist’s responses were intended to be taken seriously or not, or whether he was just relating tall tales to the writer.

The writer also indicated that some licensed physicians were conducting experiments with Dr. Sequard’s elixir. Although not conclusive, the initial findings appeared to indicate the elixir didn’t work, and at least one subject had died.

A lengthy article in the

Boston Post, April 26, 1896, went into more detail about the nature of Chinese herbalism, although it was also more sensationalist and negative in parts. The title of the article made its viewpoint clear, “

Heathen Medicine Man. Boston Chinese Doctor Drives Out the Evil Spirits of Disease.” The article began, “

There is a presumably reputable Chinese firm doing business on the lower end of Harrison avenue, who import medicinal herbs direct from the Flowery Kingdom..." It is unclear whether this was the same doctor described in the August 1889 article.

When the writer met the Chinese doctor, he described him as “

A squat, oily, almond-eyed individual, emitting a pungent odor of opium from his unkempt person,..” An obviously negative depiction of the herbalist. The writer claimed to have a severe cold in his chest and the herbalist “

inquired the nature of my ailment, my symptoms, and even my habits. To be brief, the fellow was really quite astute…” The doctor felt the writer's pulse, and then wrote a prescription (pictured above) for the writer. “ The writer paid the doctor $2.00 and then went to a Chinese clerk near the street entrance to fill the prescription.

The prescription allegedly represented 15 distinct herbs/drugs of vegetable origin. Some of these ingredients included:

Kan chaok, a hairy plant from Fukien province, that “

..,has apparently no special mission on earth.";

Kat kang, credited “

as possessing the same efficacy generally attributed to an American oyster cocktail.."; Pak cheuk, which may be regarded as a counter irritant to the fourth ingredient;

Pak chut, a sweet cordial from Chekhiang province, much used by Chinese gourmands;

Leng pak, from the bark of the mulberry tree; and

Ts un Kan, which stands high among the "

Mongolian rheumatics...." The clerk put together the perscription, boiled it in water for twenty minutes, and then advised the writer to drink it before going to bed.

The writer, through the assistance of the

Queen of Chinatown, also claimed to have witnessed an exorcism at a Chinese opium joint on Harrison Avenue. He wrote, “

In all large cities of America containing Chinese colonies, the major portion of the so-called doctors form a bastard priesthood, who practice exorcism for almost every conceivable ailment to which flesh is heir. Thus, diseases are the respective manifestations of different demons, each possessed with greater or less malignity, and it is the duty of the physician to invoke the aid of some god, using medicine only as a compliment.” However, this is basically the only reference to such exorcisms in the newspapers of this time period.

There was another lengthy article about a Chinese herbalist in the

Boston Journal, December 5, 1897, although this one identified and described the doctor,

Yee Quok Pink. Above, you can see a picture of the herbalist, a sample prescription on the left side, a picture of this office at the bottom, and the image on his sign on the right side.

Pink's office was located in a little, dingy back room at 31 Harrison Avenue. Although the reporter thought it was dirty and smelly; his view of Pink was positive, “…Yee Quok Pink can render just as good service in his humble quarters as a Back Bay doctor surrounded by modern comforts.”

Like the prior reporter, this writer had difficulty finding a doctor in Chinatown, and would later learn there might be 2-3 doctors in Chinatown, and that some prior doctors had left as the job didn't pay well. The reporter was introduced to Pink by Chung Ki Sun, a prosperous merchant, and it was noted that Pink didn't speak any English.

Pink was about 50 years old, a native of Canton, China, and also had a brother in the business. Pink started to study medicine when he was 20 years old and as there had been no medical schools near Canton, he studied under a doctor with 3-4 other people. That small group studied under four different doctors, at least for five years, and then they been practicing. Pink came to the U.S. about 20 years ago, starting to work as a doctor in New York.

About 11 years ago, around 1886, Pink came to Boston and had an office at 40 Harrison Avenue for about 5-6 years. It is possible that Pink was the first Chinese herbalist in Chinatown. Pink eventually travelled back to China for a few years, but then returned to the U.S., again first to New York. A few weeks ago he returned to Boston, seeking a good place for a permanent office.

Pink stated there currently wasn’t much sickness in Chinatown, “Chinamen pretty healthy. They hardly ever sick. When they sick they have colds, consumption and stomach trouble.” Pink noted that he treated a few non-Chinese patients too. He charged his patients based on what they were capable of paying, from maybe 50 cents for a poorer person to $2 for a wealthier one.

The reporter asked for a prescription for a cold, and Pink wrote him one, telling him to take it to a Chinese drug store, where it would cost him 50 cents. He was supposed to take the medicine ten times a day, if he had a bad cold, and only five times if he had a less serious cold. The prescription was also said to be good for consumption and stomach trouble.

Pink described some of the herbs in the prescription, including: Chun fo too, which is like ginger and is included to warm a person; Hoot sut, to strengthen the belly; Mook hant, to drive away all pain; Hoy woo, which drive the medicine to all parts of the body; Fook sing, to strengthen the bladder; and Chun sor, to strengthen the kidneys. The writer inquired why he needed all of these different herbs for just a cold and Pink replied, a “man got to have his organs working well, if he have a cold,…”

The reporter concluded, “Yee Quok Pink is an admirable representative of a Chinese practitioner. He understands his business, is methodical, conservative and enlightened. He believes that too much medicine is often a greater harm than none at all. He believes that three-quarters of all the diseases which affect mankind would cure themselves if they were given the chance.”

Pink's last thought, that many diseases cure themselves, is fascinating as a licensed physician, a white man, would say essentially the same thing in 1916, in his opposition to Chinese herbalism. I'll go into more detail about that physician later in this article.

Ever tasted

Joke Soup? The

Boston Journal, March 29, 1903, presented an article about

Dr. Yee Chong Chang, of Chinatown. Dr. Chang graduated from a Chinese medical school and came to the U.S. about 42 years, around 1861. He received a medical license from the State of Indiana and came to Boston about seven years ago, and had an office on Oxford Street.

A female reporter visited his office to interview him, and she was the first woman to ever have entered his office. He made house calls to any women who needed his medical services. They never came to his office. Dr. Chang had patients in a number of cities and towns outside of Boston, and also had some non-Chinese patients.

The reporter spoke to the doctor through his interpreter,

William F. Holske, who the Chinese hailed as a “

cousin.” Dr. Chang made “

joke soup,” but what is that? The doctor stated, “

Many are its contents, careful the preparation, long the cooking. But the result is a life giving dish which is well worth waiting for. It dispels that tired feeling, it is a tonic, mental and physical, and withal it is satisfying to the palate, which is more than can be said of most American medicine.” The reporter claimed to be sick so Dr. Chang took her pulse, and finally concluded that she wasn't actually sick.

In January 1904, advertisements started appearing for the

Foo & Wing Herb Co., located at 564 Massachusetts Avenue. In the

Boston Herald, January 31, 1904, there was a lengthy article, which potentially might have been an advertisement, like a modern advertorial. It began by discussing Chinese medicine in general, noting “

..., the Chinese still study the original medical works which were written 4000 years ago, and they still observe the leading principles laid down in those works.” It continued, "

…the practice of medicine has always been held in the very highest esteem among the people of China."

It was mentioned that, “

Every doctor holds it as a point of honor to transmit his skill and his dignities to his sons, and thus have been established lines of physicians covering many generations and handing from one to the other valuable professional secrets.” A representative of one of those families was now located in Boston,

T. Foo Yuen, formerly of

Los Angeles, having practiced there for 10 years. Curiously, his medical practice had been exclusively for whites, “

..as he has had no time to devote to those of his own race,…”

Dr. Foo's medical training began from his earliest childhood, and his study took place over 15-20 years, studying “

..., the numerous medicinal herbs of China, their medicinal properties and the best ways to prepare them into remedies;” and “

.., to study diagnosis by the pulse,…” He graduated with highest honors from the

Imperial Medical College at Pekin, entitled to rank as an

Imperial Physician, those few permitted to attend the members of the royal family.

About 12 years ago, he came to California, and spoke no English though he now speaks it fairly well. He spent his first 2-3 years in San Francisco before moving to the milder climate of Los Angeles, establishing the headquarters of

Foo & Wing Herb Co. at 903 South Olive Street. “

This corporation deals in prepared remedies under its own trademark, and also imports and sells a few articles of pure and wholesome foods for the use of its patrons, such as the best Chinese rice that can be procured and a certain brand of tea that is especially adapted to the use of invalids.” Dr. Foo had also written a number of books on Chinese medicine.

The article/ad continued,“

But the genuine system of Chinese, or Oriental, medicine is simple, clean, consistent and effective. And this is the universal verdict of the intelligent men who know most about it.” It was noted that over 3000 varieties of medicinal herbs existed, but commonly only 300-400 were used. The medical system relied on pulse diagnosis, where “

..the physician asks the patient no questions whatever, but determines his bodily condition, the seat and extent and nature of the disease, in every instance, solely and entirely by feeling the pulse of both wrists.”

Dr. Foo's partner was

Dr. Tom Wing, a skilled physician and a distant relative of Foo. Dr. Wing had lived in the U.S. for about 20 years and spoke English very well.

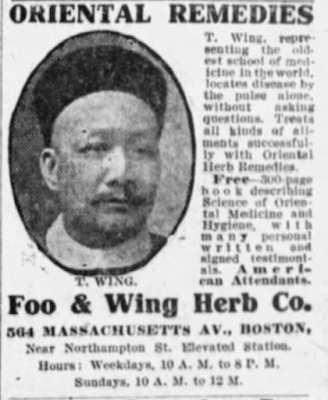

An advertisement for

Foo & Wing Herb Co. in the

Boston Post, February 10, 1904: noted, “

The Oriental method of diagnosis by the pulse alone, three fingers being used upon each wrist, which will tell exactly where the seat of your disease is located.”

Another advertisement in the

Boston Globe, February 28, 1904, had a photo of Dr. Foo. The ad also stated, “

Their method of diagnosis is by the pulse alone, which will tell where your disease is located without asking questions.” People were encouraged to visit the doctors, and their diagnosis would be free. In addition, they would receive a copy of a 300 page book, a “

guide to health and how to keep well.” It provided many recipes for cooking nutritious and attractive dishes for the sick, useful hints on diet, lessons on anatomy, bodily exercises, and more. The ad also offered free medicine for a week for any patient who began treatment before April 10, 1904.

The

Boston Post, April 16, 1904, had another advertisement which gave a photo of Dr. Tom Wing.

In another advertisement, in the

Boston Globe, May 28, 1904, for Foo & Wing Herb Co., there was a reproduction of a page from an ancient Chinese medical book, although the ad didn't explain what that page depicted.

The

Boston Journal, May 16, 1904, reported on the death of

Lee Hay Wey, alleged to be the only Chinese doctor in Boston, although that didn't actually appear to be true. Wey had only been 36 years old, unmarried, wealthy, and died from tuberculosis. He graduated from a Chinese medical university and came to the U.S. about 12 years ago. He lived for two years in San Francisco, before moving to Boston. For five years, his office was at 9 Harrison Avenue. I couldn't find any other newspaper references concerning him, except about his death.

There were brief mentions of another Chinese doctor in the

Boston Globe, February 12, 1907 and

Boston Globe, July 25, 1907.

Dr. Yee Chong Chin (who is probably the same as the previously mentioned Dr. Yee Chong Chang) had an office on Oxford Street, and he stated that only three 3 Chinese were too sick to participate in the Chinese New Year’s celebrations that year.

Another brief mention. The Boston Globe, June 3, 1911, reported that Lou Quey, known as the "lung doctor" in Chinatown, and with an office at 32 Oxford Street, was fined $50 for possession of opium.

The Boston Globe, June 29, 1911, noted that Dr. Tom Wing and his wife, who lived at 561 Massachusetts Avenue, just had a baby girl. The advertisements for Foo & Wing Herb Co. largely continued through March 1913, and at some point Dr. Foo returned to Los Angeles, apparently leaving Dr. Wing behind to run the business.

Up to this time, Chinese herbalists weren't legally considered to be medical doctors so they could, and some were, charged with unlawfully practicing medicine without a license. They would generally be fined, and then simply continue acting as an herbalist. It almost seemed that such fines were just seen as a part of their business. Sometimes the Chinese would claim they were only "herbal merchants" and not doctors, trying to avoid prosecution. In 1914, efforts were initiated to recognize herbalism as a legitimate medical practice and allow them to be licensed, but such efforts wouldn't be successful.

One of the sponsors of the bill was Rep. McGrath of Boston, and the primary impetus for the bill was Pang Suey, a famed Boston herbalist, who had even treated McGrath's father. Pang had been charged with illegally practicing medicine on multiple occasions. However, Pang, a graduate of the University of Canton, China, had many supporters, claiming that his treatments had resolved their medical issues.

An adverse reported, created by the Ways and Means Committee, was rejected by a vote of the House. The main opposition to the bill came from Rep. Warner of Taunton, who stated that Pang Suey refused to learn English and thus refused registration as a physician. However, Rep. McGrath countered that Pang was willing to take an examination on the type of medicine he practiced, which was very different than what American doctors were taught.

The Boston Globe, February 25, 1916, reported that on the prior day, the Legislative Committee on Public Health held a hearing on the herbalist bill. Over 50 patients of Pang Suey were present to support the measure and there was also a petition signed by over 2100 people in favor of the bill.

Next, the Evening Herald, March 8, 1916, reported that the Legislative Committee on Public Health held another hearing on the herbalist bill. Dr. Richard C. Cabot opposed the bill, stating he was convinced the evidence he had heard was that Dr. Suey didn’t know for what he was prescribing. In response to some of Suey's patients, Cabot replied, “Most people who go to a doctor for treatment recover of themselves. Most diseases have a tendency to get better, and we who are doctors often known, when we are treating people, that our remedies do not cure. Nature does the work.” Dr. Walter Bowers, the secretary of the State Board of Registration in Medicine also opposed the bill. He had examined Dr. Suey and claimed he the lacked the knowledge of medicine demanded of licensed practitioners.

We return to the words of Yee Quok Pink from 1897, who stated "... that three-quarters of all the diseases which affect mankind would cure themselves if they were given the chance.” Dr. Cabot's words above echo those words, showing that Chinese herbalists and American licensed physicians may share some commonalities.

Dr. Cabot ventured to Dr. Suey's home and office, to gather more information. The

Boston Globe, March 9, 1916, reported that

Dr. Richard C. Cabot, assistant professor of Harvard Medical School, and leading Back Bay practitioner, went to Pang Suey's home, on the north side of Dartmouth Street, near Appleton. It was noted that Suey had originally practiced medicine in the province of Kwantung, and “

whose medical learning came to him through a member of the staff of the Chinese Medical Academy at Pekin.” For about 10 years, Suey, who is now 49 years old, had been dispensing herbal medicine in Boston.

Pang also stated that he is ..“

a regularly enrolled physician in China; that under the old system there, before the Revolution, it was the custom for a medical student to obtain his credentials as a doctor from the physicians under whom he studied." His certificate as a doctor was attested by the American Consul at Hong Kong and by the Imperial Chinese Embassy at Washington.”

According to the laws of Massachusetts, "

... no doctor may practice in this State who has not passed an examination in writing before, and been registered by, the Board of Registration in Medicine.” There were some accepted exceptions, and some wanted to add another exception, for herbal doctors. The bill was originally introduced by

Harold L. Perrin of Wellesley, seeking to add an exception for “

registered pharmacists or persons dealing in natural herbs in prescribing gratutiously.”

Pang explained that he made a diagnosis by pulse alone. “

It is a method recognized in China for hundreds, and perhaps thousands, of years.” He would then write a prescription, which was filled in the basement of his house, “

where his private herbarium is maintained, in charge of a Chinese dispenser.” He charged only for the herbs, and not the consult, and thus, “

He does business as a person dealing in natural herbs and not as a doctor.”

There were a number of clients at Pang's home, ready to speak to Cabot and vouch for Pang. Interestingly, none of these clients were Chinese, and they came from Boston and the suburbs, with three even arriving in limousines. This was clearly intended to impress Cabot and others, to indicate the fame of Pang wasn't restricted to the Chinese community.

For the finale, a girl came in for a consult, and she hadn't visited Pang before. Pang felt her pulse, holding her left wrist first for a minute and then her right wrist. There was a plate glass screen, suspended on two cords, that shielded Pang from her breath, but allowed him to reach and check her pulse. The only question he asked the girl was her age, and he then stated “Your circulation is poor, and you have a pain in your back, here,’ indicating the seat of the pain. The girl confirmed his words.

In April 1916, the bill passed the Senate but the House of Representatives rejected it. There was another hearing on the matter in March 1917. The Boston Globe, March 6, 1917, reported that at the hearing there was nearly a fistfight between Walter P. Bowers of the State Board of Registration in Medicine and Representative Joseph B. McGrath. Bowers spoke to the committee and McGrath claimed he didn’t tell the truth, and they almost started fighting. The hearing also ended, abruptly, with much hissing by a number of women who were present.

Unfortunately, the bill lost some of its purpose as the Boston Globe, April 23, 1917, stated Pang had died, “famous for the healing herbs he dispensed to hundreds of people in this city,..” Efforts to pass the herbalist bill would continue for a few more years, but without Pang, it lost much of its impetus.

After the death of Pang Suey, about $178,000-$184,000 in cash was found in his home on Dartmouth Street, hidden in mattresses, under rugs, behind pictures, and elsewhere. This would be tied up in probate for six years before its final resolution.

The Boston Globe, June 20, 1918, reported Tom Foo Yuen, currently of Los Angeles, and Joe Lop Wai, of China, sought a share of Pang's estate. They claimed they had a partnership agreement with Pang, which indicated how much they were owed. Prior to 1909, Foo said Pang “was employed by him, assisting him as a dispenser of herbs of curative power,..” Foo had also sent Pang to China to make a study of herbs.

When Pang came to Boston to start a business, Foo advanced him $3300 and a partnership agreement was drafted in which both would share the profits equally. Later, a new agreement was drafted and Wai was admitted as a partner. The new agreement split the profits, with Pang receiving 3 parts of 11, Wai 2 parts of 11, and Foo 6 parts of 11. In addition, Foo alleged that Pang had claimed he was working at a loss, but had actually concealed about $200,00 in profits from his partners.

Back tracking a little, Pang had an assistant in his herbal business, Joey Guoy Shong, who would become the first husband of the famed Ruby Foo. Upon Pang's death in 1917, Shong started residing at his Dartmouth home, took over the herbal medicine business, and became the administrator or of Pang's estate. In December 1918 and September 1923, Shong was charged with practicing medicine without being registered, both times being found guilty and fined about $100 each time.

The Pang estate controversy continued. The Boston Globe, October 21, 1919, reported that Joe Lop Wai, patriarch of the Joe family of the world, and one of China’s greatest herbal doctors, died, penniless. He was was 73 years old, and it was alleged he died of a “broken heart” by disappointment and postponement of the probate matter of Pang, his nephew. In June, Joe and Foo had come to Boston to contest the estate, but there had been delays.

When Pang’s herbal business in Boston wasn’t doing well, Foo sent Joe to help him, and Joe remained for 3-4 years until the business “had reached a paying basis.” Then, Joe returned to LA and eventually China. In China, there had been a partnership agreement, and Joe was awarded 4-11 of the estate, but that that ruling obviously had no validity in the U.S.. Resolution of this probate matter was still several years away from resolution.

In December 18, 1919, Dr. Tom Wing, who had been Foo's partner in Foo & Wing Herb Co., died the day before. The business would continue though. In April 1920, Dr. Foo :moved back to Boston and took up residence at 497 Columbus Avenue.

Resolution for Pang's estate. The Boston Globe, August 8, 1923, noted that Dr. Pang's wife and son would receive substantially all of his estate. The claims of Foo and Joe were rejected, and Shong apparently received only a small amount, mainly to pay expenses.

The Boston Globe, March 29, 1929, noted that Peter Chan, about 35 years old and the proprietor of Foo & Wing Herb Co., was arrested by State Police for unlawfully practicing medicine without registration. The police seized a truckload of Chinese foods and herbs.

Despite this illegality, Chinese herbalists would continue to operate, as they had done for the past forty or so years in Boston, and still are in existence today. These herbalists had much support from their patients, both Chinese and non-Chinese, and their main opposition appears to have been licensed physicians. Now, as you wander the streets of Chinatown, and see one of the herbalist shops, you'll understand better some of their local history.

A History of Boston's Chinatown and Its Restaurants: Check out Part 1,

covering the 18th & 19th centuriesCheck out Part 2, covering the years 1901-1920Check out Part 3, covering the 1920s.Check out Part 4, covering 1930-1959 Check out Part 5, covering the 1960s

Check out Part 6, the tale of Ruby Foo. Check out Part 7, the tale of Anita Chue

Check out Part 8, the tale of Mary YickCheck out Part 9, a Deeper Look into Two Restaurants

And also see my

Compilation Post, with links to my additional articles about Chinese restaurants, outside Boston and in Connecticut, as well as a number of related matters.